This is the first of six articles about the Cantigas de Santa Maria – Songs of Holy Mary – composed by the King of Castile, Alfonso X, and unnamed assistants between 1257 and 1283. Most medieval music enthusiasts will be familiar with the manuscripts’ many depictions of medieval musicians and their instruments, and with some of its 420 songs. These six articles focus on the influences behind the compositions and the contents of the songs, and will be followed by two stand-alone articles about the historical principles upon which a medieval musical arrangement may be made, focussing primarily on the Cantigas.

In order to understand the background to the Cantigas de Santa Maria, we must first appreciate a medieval musical movement which may at first appear unrelated, but which is fundamental to both the music and theology of Alfonso’s compositions: the troubadour tradition. In this article, we see that troubadour influence not only spread well beyond its home in Occitania (southern France), it had a profound effect upon the Catholic faith Alfonso inherited. The Catholic response to troubadour songs, which the church perceived as spiritually corrupt, was to develop a new Mariology, a major shift at the heart of Catholic worship. It was within this context that Alfonso composed the Cantigas de Santa Maria.

We begin with a performance (in English) of Cantiga 260, which praises the Virgin in terms that exactly mirror troubadour love poetry, while also criticising troubadours for not praising her.

A performance in English of Cantiga de Santa Maria 260: Tell me, o you troubadours

(Dized’, ai trobadores). The meaning of this song is explored in the second article of this series.

Who were the troubadours?

The troubadours were the poets and singers of Occitania, what is now southern France. From the late 11th century to the end of the 13th century, they developed several styles of song, most famously the poetry of fin’amor – refined or perfect love. Their influence was widespread and considerable, extending well beyond southern France and long after the lifetimes of troubadour writers.

Troubadour means maker or finder, which relates to their method of song-writing, typical for the time: they either composed entirely new poetic and musical material, or used an existing or found melody, writing new lyrics on established themes for the given genre. A typical fin’amor song would express some or all of the ideas that: the object of love is perfect, beautiful, noble, virtuous; the writer’s life would be complete and he would be forever happy serving her; but she is unattainable so his heart is broken. There have long been scholarly debates over whether the troubadours were the creators of fin’amor or the developers of a previous Arabian-Hispanic tradition, which the evidence does seem to indicate. What we can say for sure is, whether or not the troubadours created the tradition, they developed and promulgated it in western Europe with unprecedented literary popularity: around 2,500 of their song lyrics survive. When Latin still dominated learned public discourse, troubadours and trobaritz (female troubadours) wrote in the vernacular, langue d’oc, or Occitan, the language of what is now southern France, what was known from the 13th century as Occitania.

When the troubadour tradition spread beyond Occitania, songs were written in the vernacular of their location. In northern France, the composers were known as trouvères; then the tradition spread south, east and northeast to Italy, Iberia and Germany, the Italians known as trovatori and the German writers known as Minnesänger. There are no surviving secular love songs in English before the anonymous bird on a briar (bryd one brere) of c. 1290–1320, so any troubadour influence on lyrics in English before then is lost, but the evidence suggests that what is lost will have carried troubadour characteristics. Eleanor of Aquitaine married England’s King Henry II in 1152, and the troubadour, Bertran de Born, served at Henry’s court in Argentan, northwest France. Another troubadour, Bernart de Ventadorn, followed the Queen to England to be part of the Plantagenet court. Eleanor’s son, Richard I, or Richard the Lionheart, ascended the English throne in 1189, wrote his own songs in Occitan, and was mentioned by name in songs by Bertran de Born. This intimation of the troubadour tradition in England in the 12th century through the royal retinue may explain why bird on a briar (full articles on this song by clicking here and here), the earliest surviving secular love song in English at the end of the 13th century, follows the framework of the troubadour poem: she is perfect, beautiful, noble, virtuous; the singer is so happy when he sees her; his life would be complete and he would be forever happy serving her; but she is unattainable so his heart is broken.

Pure or refined love was known as fin’amor, and it combined the formal constraints of poetic lyrical forms with great creativity, artistry and passion. For example, from Bertan de Born’s He protests his innocence to a lady, 12th century:

in a 13th century French manuscript, BnF

12473, folio 160r. (As with all pictures,

click to enlarge in a new window.)

Pardon, my lady, but I didn’t do

what your flatterers have accused

me of. Don’t let a spat arise

between your person – humble, true,

loyal, generous, pleasant too –

and me, my lady, through their lies.

On its first flight, may falcons tear

my hawk from wrist and pluck it bare

before my eyes and leave it dead,

if I do not prefer you over

any other willing lover

who’d like to keep me in her bed.

Sometimes the passion was more subdued, as in When days grow short by Peire d’Alvernhe (Peire Rogiers or Rotgiers de Rougier, or d’Alvergna or de Mirapeys), 12th century:

The text says, “Peire Rogier was from

Auvergne, a canon of Clermont”. From a

13th century French manuscript,

BnF ms. 854, folio 12v.

When days grow short and night advances

and the air grows clear and darkens,

would that my thoughts put forth fresh branches

to bear with joy new fruit and blossom,

for I see the oaks reft of their leaves,

while nightingale, thrush, woodpecker and jay

shiver with cold, and from the chill retreat.

The vision that sustains me through

these times is of my distant love:

sleeping, waking, what matters to

him who from his love is removed?

Love wants joy: in times when strife is looming

he who can banish care, it’s safe to say,

with his love is inwardly communing.

Despite this passion, counter-cultural to the Catholic Church, the troubadours were in other respects socially conservative. Some of them went to fight in the Crusades and wrote songs about doing so. They clearly thought of themselves as good Catholics, though not all troubadours thought those holding Church office were good Catholics, and some were forthright in opposing them. The Catholic Church considered the troubadours to be dangerous sexual deviants. The teaching of the Church was that physical or emotional pleasure has no spiritual value, so sex is sinful, even within marriage, unless for the sole purpose of procreation. Therefore, the only way a good Catholic songwriter could introduce erotic desire into a lyrically-imagined relationship was as a fantasy about an unobtainable woman. In an age when divorce was impossible and the class system was enforced by law, what better way to make a love interest unobtainable than to make her a married woman of a superior social class, the wife of your patron?

The troubadours were from a variety of social classes, and wrote largely for feudal nobles. Despite this class diversity, troubadour love is always declared for a noblewoman: only the highborn are worthy, only they can have the desired characteristics of a love-object. The songs preserve and rely on the power of lords and ladies over their helplessly faithful servants, withholding from them the love they desire, to the point that troubadours often address their lady in song by a portmanteau expressing that power, comprising the feminine mia, my, and the masculine domnus, lord, to make midons. Courtly expressions of love were coded expressions of feudal allegiance.

In the vidas, short biographies of troubadours in the manuscripts of their songs, there are some examples of actual trysts between the songwriter and his patron’s wife, but it is difficult to know how much to trust such stylised accounts which rely so much on the contents of troubadour lyrics. On the whole, it may be safe to assume that the patron, the husband of the love object, thought it flattering that his wife was thought of in this way, and knew it was safe, that such love would only ever happen within the lyrical boundaries of a song, that he knew it was an exercise in poetic artistry, form and artifice. No doubt it performed that longstanding medieval (and later, renaissance) function of flattery of the powerful patron, the servant extolling his master’s virtues or, in this case, his master’s wife’s virtues. As with all formal flattery, the unrequited love interest was rarely elevated to the level of an actual person: she was an ideal type, a category, addressed in an artistic but formulaic manner.

The sin of sensual desire

Still, the troubadours were writing openly of physical desire for a married woman, the anticipation of its joys, the sadness and frustrations of it being withheld. For the church, to imagine adultery was as immoral as doing it, so fin’amor songs were an engagement in and encouragement of sinful carnal pleasures. The English Benedictine monk, Orderic Vitalis (1075–c. 1142), chronicler of Normandy and Anglo-Norman England, described in a sermon the changing culture around the time of the first troubadours: “effeminate men … dirty libertines who deserve to burn in hellfire” because they get drunk, “please the women with all kinds of lasciviousness”, “reject their warrior customs and laugh at the exhortations of the priests.”

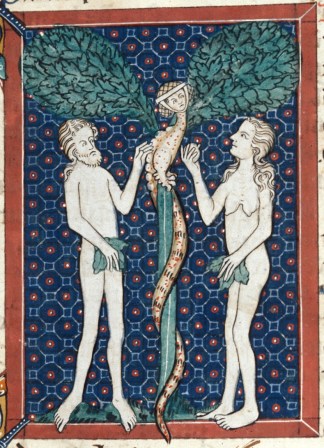

The troubadours’ celebration of sensual desire was in complete opposition to the teaching of the Catholic Church that had been continually repeated and unchanged since the 3rd century when Church Father, Tertullian (c. 155–c. 240), wrote On the Apparel of Women. Tertullian argued that women should “go about in humble garb … walking about as Eve, mourning and repentant, in order that by every garb of penitence she might the more fully expiate that which she derives from Eve – the ignominy, I mean, of the first sin, and the odium (attaching to her as the cause) of human perdition … You are the devil’s gateway; you are the unsealer of that (forbidden) tree; you are the first deserter of the divine law; you are she who persuaded him whom the devil was not valiant enough to attack. You destroyed so easily God’s image, man. On account of your desert – that is, death – even the Son of God had to die.” In other words, a woman – any woman, every woman – represents temptation and sin in her very being, a devilish snare to any God-fearing man. It was woman – the first woman, every woman – who crucified Christ.

Thus it was that by the middle of the 2nd century, the Virgin Mary’s role had become established by Christian writers as the new Eve. Just as Eve, mother of the living, had played her part in Adam’s sin, leading to the Fall of all humanity in the Garden of Eden, so Mary played her part in God’s incarnation, leading to the salvation of all humanity through the new Adam, Jesus. As Justin Martyr (died 165) put it in his Dialogue with Trypho, Eve was the “disobedient virgin” who brought death and disobedience to humanity, and Mary the “obedient virgin” through whom the saviour was born.

This contrast between Eve and Mary is Alfonso’s entire theme in CSM (Cantiga de Santa Maria) 320:

Holy Mary restores the good which Eve lost.

The good which Eve lost through her temerity,

Holy Mary regained through her great humility.

The good which Eve, our ancient mother, lost,

Holy Mary recovered when she befriended God.

The good which Eve lost when she lost Paradise,

Holy Mary recovered through her great wisdom.

The good which Eve lost when she lost fear of God,

Holy Mary regained by believing in him without question.

The good which Eve lost by breaking the commandment,

Holy Mary regained through good understanding.

All the good Eve lost through committing great folly

was regained by the glorious Holy Virgin Mary.

and the Virgin Mary (in blue, left) side by side. Eve is pulling fruit from the forbidden tree of

knowledge of good and evil, the site of the Original Sin which damned all humanity, known as

The Fall. The tree has a death’s skull in its foliage, and Eve is handing out the fruit of sin, with

the figure of Death looming over the recipients. Mary’s side of the tree has God’s solution,

Christ sacrificed, and Mary is picking Eucharistic wafers – the transubstantiated body of

Christ – from the tree to give to worshippers, with an angel standing over them.

In complete contrast to Tertullian and the rest of the Catholic hierarchy, the troubadour view of a woman is as an object of desire, longing and love, giving a man feelings that dominate his life in usually unfulfilled ecstasy. His chief aim is to win her, knowing that her physical beauty and the moral virtues she radiates will make his life complete. The troubadours rarely used Eve imagery, but when they did it did not conform to the teachings of the church. For Guillaume IX of Aquitaine (1071–1127), Eve is not the evil downfall of Adam, a figure of repulsion, but the primal divine beauty who filled Adam with desire. From Guillaume‘s I’ll make a little song that’s new:

For her I shiver and tremble

since with her I so in love am;

never did any her resemble

in beauty, since Eve knew Adam.

Though the fin’amor tradition does also depict women negatively, it is never the one-dimensional view of evil womankind propagated by the Church, but nuanced: the object of desire is both glorious and divine and the man’s downfall, thus his experience of her is expressed in emotional and poetic oxymorons. To take two typical examples from trouvère lyrics, in The year that rose, Conon de Béthune (before 1160–1219) expresses the emotional complexity as “she makes me live in a confusion of grief and joy”; and in I will fashion a song while fancy strikes me, Thibaut de Champagne (1201–1253) writes, “Lady, for you I want to go around like a fool, for I love the grief and pain I have from you … my great suffering for you pleases me so”.

A new Mariology

Mary played an important supporting role in Catholic theology and was the role model for women in the early church – the subservient, obedient, virginal mother. But until the 12th century the Catholic Church had not developed a systematic Mariology or a pattern of worship with a special elevated place for her. This came as a result of the unwelcome influence of fin’amor. In the 12th and 13th centuries there was a huge expansion of Mary’s role, developed particularly by Benedictine monks, putting Mary centre stage to the point where she became more prominent than Christ or God and was often seen in iconography as a lone figure, not a corollary of the Father or the Son. The Catholic Church seems to have decided that it was not possible to successfully counter the popularity and influence of troubadour and trouvère lyrics and their sensual portrayal of women, so they co-opted fin’amor. Key in this movement were two French clerics, Cistercian abbot Bernard of Clairvaux (1090–1153) and Pope Clement IV (1265–1268).

Though only a small amount of Bernard of Clairvaux’s writing is about Mary, he did formulate a concise and influential Mariology which stressed the role of the Virgin as the Mediatrix, the intercessor or prayer-intermediary between believers and Christ/God, whereby praying to Mary brings emotional sustenance and spiritual relief from anguish. Significantly, Bernard is also remembered as the subject of Mary’s lactatio, the milk wonder, an event which is supposed to have happened at Speyer Cathedral, Germany, in 1146. There are variants of this sensual, spiritual, maternal event in writing and in art, consisting of Mary baring her breast and sprinkling her milk on Bernard’s lips. In some versions he is asleep, in others it is a waking vision. The religious significance is that it shows Mary’s eternal motherhood, her motherhood of believers as well as Jesus, her eternal presence and ability to perform miracles. In the middle ages and renaissance, milk was understood to be processed through a combination of blood and bodily heat, thus linking both Mary and the milk-receiving believer to Christ’s sacrifice. In some versions, the milk gave Bernard wisdom, in others it cured his eye infection. Bernard of Clairvaux’s spiritual relationship with Mary, his place in Catholic history and his contribution to Mariology earned him the title of Mary’s troubadour. This is a title, as we shall see, that Alfonso also took for himself, since worship and elevation of Mary is fundamental to Alfonso’s Cantigas.

Left: Simon Marmion, Saint Bernard’s Vision of the Virgin and Child, 1475–1480.

Right: from MS Douce 264, folio 38v, Bodleian Library, Oxford, 16th century.

A similar miracle to that granted Bernard of Clairvaux appears as CSM (Cantiga de Santa Maria) 404, which states that Mary’s milk “nourished him who holds us in his power … created us from nothing and … should take away evil and bring good.” The story is of a priest who “committed so many evil deeds” but “loved Holy Mary above all else”. While praising Mary, he falls into a delirium, eats his tongue, tears his lips, and “his mouth and nose swelled so much, as the book tells, that they could not distinguish where his face ended and his neck began.” He is miraculously cured because an angel takes pity on him and calls Holy Mary, who “uncovered her breast and anointed his face and chest with her milk and thus cured him … After he had slept as a healthy man sleeps, he recovered from the malady which had made him mad, and he understood that he had been wise to worship Holy Mary.” Another kind of lactatio miracle appears in CSM 46, where the breasts of an image of Mary in the ownership of a Moor become real and flow with milk, leading to his conversion; and the motif also features in CSM 360: “… how can God be angry with us when his mother shows him her breasts with which he was nourished and says, ‘My son, by these I beg you that these people of mine be pardoned and sit in your company.’”

of a Moor becoming real, flowing with milk, and, behind him, the spiritual presence of

Virgin and Child enacting the miracle which leads to his conversion.

The other key figure in the elevation of Mary to counteract the corrupting sinful influence of fin’amor was Pope Clement IV. Clement was raised in the langue d’oc, the troubadour region. His poem on the seven joys of Mary inspired a whole genre of poetry, song, and worship, and is an early version of the Franciscan rosary.

An outline of the general characteristics of this new Mariology shows it to have been taken directly from fin’ amor lyrics, countering and diffusing the sensual power of adulterous fantasies by co-opting them as desire for the chaste Virgin: a description of the love object’s perfection matched by her physical beauty was transformed into descriptions of the Virgin’s physical beauty and perfection; the desire of the singer to be worthy of the virtuous woman became the desire of the believer to be worthy of virtuous Mary; just as the influence of the superior lady is ennobling, so is Mary’s influence; troubadour lyrics had the lover bound in submissive service to his lady just as a knight is bound in service to his lord, and so the Church developed the idea of the believer bound in service to Mary as a knight or chaste lover; and now, unlike in troubadour lyrics, the love object is attainable, through prayer and obedient religious service.

The remoulding of Mary in the image of fin’amor was a dramatic international success, seen in all subsequent Mariological literature and song, practically established in the Catholic calendar through multiple Marian feasts by the end of the middle ages. An early English example of such Marian imagery is found in Edi beo þu heuene quene (Blessed are you, queen of heaven), written anonymously in a manuscript in Llanthony Priory in Gloucestershire, dated 1265–1290s (about which there is an article here). A few lines show the unmistakable influence of the troubadours (translated here into modern English):

There is no maid of your complexion, fair and beautiful, fresh and bright.

Sweet lady, on me have compassion and have mercy on me, your knight …

You bring us out of care and dread that Eve so bitterly for us brewed,

you shall us into heaven lead, so well sweet is that heavenly dew …

Mother, full of noble virtue, maiden so patient, lady so wise,

I am in your love now bonded, and for you is all my desire …

Virgin worship did not eclipse fin’amor and enforce conformity in all Catholic hearts. For example, Peire Cardenal served the Provençal Church as a canon in the 13th century, but abandoned the Church for “the vanity of this world” according to his vida (account of his life), opposing the clergy and clerical celibacy (there is some evidence that he may have married); Raimon de Cornet in the 14th century, also in Toulouse, was both a priest and a troubadour, opposing the clergy and the papacy and praising the pleasures of music, poetry and dance; and the English monk who wrote bird on a briar on the back of a papal bull clearly had the amorous tradition of fin’amor in mind, not the bowdlerised Marianised vision of love promoted by his church.

But these are individual contrary examples: the tide had irrevocably turned, and the Catholic Church’s attempt to diffuse the influence of troubadour love by absorbing it into Virgin worship was a huge success, changing Catholic theology and practice to the present day, nearly a millennium later. In Occitania, where the roots and heart of the troubadour tradition resided, where so many could not be turned away from fin’ amor by theological persuasion, the troubadours would eventually be crushed by force.

War on Occitania

Right: Massacre of Albigensians by the crusaders.

From British Library, Royal 16 G VI, folio 374v, 1332–1350.

In 1208, Pope Innocent III declared the Albigensian Crusade against the Albigensians or Cathars, a religious group declared heretics due to their denial of the validity of clerical office, their declaration of gender equality, their criticism of the church’s accumulation of land, and their reading of the Bible for themselves. As an incentive to slaughter, Pope Innocent said any French nobleman who joined the crusade and took up arms against the Cathars was entitled to their land. The Cathars lived in Occitania, and the crusade against them was commonly perceived as a war on the region as a whole: it was not under French rule, so it followed that a key prize of this crusade was winning the territory for the French crown. By the end of 20 years of carnage, from 1209 to 1229, thousands of Cathars were massacred, the county of Toulouse was under French rule and Provençal society was destroyed, with the favourable consequence for the Catholic Church that the troubadours of the langue d’oc were virtually wiped out.

In 1233, Pope Gregory IX commanded that the Dominican Inquisition completely exterminate the Cathars. Between the end of the Cathar Crusade and this papal final solution, the troubadour Guiraut Riquier was born in Narbonne, Occitania (c. 1230–1292). We can only imagine what he witnessed as a child and a young adult of the destruction of his region and the dying light of his native musical tradition. From 1254 he served Almarich IV, Viscount of Narbonne, one of the few still willing to be a patron to a troubadour. When Almarich died in 1270, Guiraut made his way to Iberia, and from 1271 to 1279 he served in the court of King Alfonso X. Guiraut was not the first troubadour to find a home in Alfonso’s court, or in the Iberian peninsula more generally, and he happened to arrive halfway through Alfonso’s composition of the Cantigas de Santa Maria.

The next article explains that Alfonso X was already steeped in the troubadour tradition when, in 1257, he began to compose the Cantigas de Santa Maria as the Virgin Mary’s troubadour. As we will see, his motives, like his life, may have been less than pure.

Translation credits

Translations of Ieu m’escondisc, domna, que mal no mier (He protests his innocence to a lady) by Bertan de Born and Deiosta-ls breus iorns (When days grow short) by Peire d’Alvernhe are by Robert Kehew – see bibliography.

The translation of Farai chansoneta nueva (I’ll make a little song that’s new) by Guillaume IX of Aquitaine is by A. S. Kline – see bibliography.

The translation of Edi beo þu heuene quene (Blessed are you, queen of heaven) into modern English is by the author of this article, Ian Pittaway.

The translations of the Cantigas de Santa Maria are by Kathleen Kulp-Hill – see bibliography.

My role in creating English verses in the videos that accompany these articles was to recreate, as far as possible, the original syllable count and rhyme scheme. The versification in English of CSM 260 and the musical arrangement are © Ian Pittaway.

Bibliography

Akehurst, F. R. P., & Davis, Judith M. (ed.) (1995) A Handbook of the Troubadours. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Gaunt, Simon, & Kay, Sarah (1999) The Troubadours. An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kehew, Robert (ed.) (2005) Lark in the Morning. The Verses of the Troubadours. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Keller, John Esten (1967) Alfonso X, El Sabio. New York: Twayne Publishers.

Kline, Tony (2009) From Dawn to Dawn: Troubadour Poetry – a selection of sixty Provençal poems, translated from the Occitan. [Online – click here to go to website.]

Kulp-Hill, Kathleen (2000) Songs of Holy Mary of Alfonso X, The Wise. A translation of the Cantigas de Santa Maria. Tempe, Arizona: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies.

Martínez, H. Salvador (2010) Alfonso X, the Learned: A Biography. Translated by Odile Cisneros. Leiden: BRILL.

McDonald, James (2016) Cathars and Cathar Beliefs in the Languedoc. [Online – click here to go to website.]

O’Callaghan, Joseph F. (1998) Alfonso X and the Cantigas De Santa Maria: A Poetic Biography. Leiden: BRILL.

Roberts, Alexander; Donaldson, James; & Coxe, A. Cleveland (1885) Ante-Nicene Fathers, Volume 4 (Buffalo, New York: Christian Literature Publishing Company)

Scaglione, Aldo (1991) Knights at Court: Courtliness, Chivalry, and Courtesy from Ottonian Germany to the Italian Renaissance. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Available online – click here to go to website.]

© Ian Pittaway. Not to be reproduced in any form without permission. All rights reserved.