The rebec is a late medieval and renaissance gut-strung bowed instrument with 3 strings, its body carved from a solid piece of wood. Its sound has a nasal quality, unlike the more full-sounding modern violin, which shares some of the rebec’s characteristics: strings played with a bow, a fretless neck, a curved bridge to allow strings to be bowed singly, and a soundboard carved to have a gentle upward curve. Distinguishing the rebec from other medieval and renaissance bowed instruments, in particular the vielle (medieval fiddle), has been a matter of some contention until more recent scholarship re-evaluated the primary evidence.

The rebec is a late medieval and renaissance gut-strung bowed instrument with 3 strings, its body carved from a solid piece of wood. Its sound has a nasal quality, unlike the more full-sounding modern violin, which shares some of the rebec’s characteristics: strings played with a bow, a fretless neck, a curved bridge to allow strings to be bowed singly, and a soundboard carved to have a gentle upward curve. Distinguishing the rebec from other medieval and renaissance bowed instruments, in particular the vielle (medieval fiddle), has been a matter of some contention until more recent scholarship re-evaluated the primary evidence.

Though the rebec has gained a reputation as a medieval instrument, it was still being played beyond the renaissance and to the end of the baroque period in western Europe, by now having fallen from grace from a regal courtly instrument to one of lowly street entertainment.

This article begins with a video of Igor Pomykalo playing an Italian Saltarello, c. 1400, on rebec.

Italian Saltarello from British Library Add MS 29987, folio 62r,

dated c. 1400, played on rebec by Igor Pomykalo.

Origins: the rebab?

The origin of the rebec is now widely believed to be in the similarly named Arabian rebab or rabab, thus the development of variant names is presumed to include rubeba, rubeb, rebecca, rebeccum and rebec. However, caution is needed. As anyone familiar with early music nomenclature is aware, similar or even identical names do not necessary signify the same instrument. (Much more on this subject here.) The link between rebab and rebec seems to originate from Ian Woodfield, The Early History of the Viol (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984), but this is conjecture, and there is no primary evidence linking the two instruments.

The first brief mention of the rebab in writing is in 9th century Arabia. A more clear description appears in 1377 by Tunisian scholar Ibn Khaldun. In his Muqaddimah (Introduction to History), he described the rebab being played with a bowing string attached to a bent shaft, rubbed with resin and drawn across the two playing strings. In 13th century France, music theorist Jerome of Moravia wrote his Tractatus de Musica, c. 1280, in which he stated that the “rubeba” was “a musical instrument played with a bow”, as if it was new to his readers and had to be explained. He described it having 2 strings a fifth apart, c and g, and it was less important (in France at this time) than the 5 string vielle (medieval fiddle).

apparently largely composed by King Alfonso X, written 1257-1283. None of the

instruments in the Cantigas are labelled, in common with almost all medieval illustrations.

On the right we have an oud played with a 2 string rubeba or rebab, the latter conforming to

the 13th century description by Jerome of Moravia (see above). On the left we have two rubebas,

also conforming to Jerome’s description. (Click picture to see larger in new window.)

The first extant evidence in writing for the word rebek is in an early 12th century table of Arabic and Latin terms (Paris, Bibliotheque Nationale, Ms. lat. 14754), and this is where it begins to get complicated. There is no illustration with that Arabic/Latin table so, with the notorious fluidity of medieval instrument naming, we cannot be entirely sure what was meant by rebek, and cannot necessarily assume it was the rebec we are seeking, nor is there any suggestion of a connection to the rebab. Writing nearly 2 centuries later, Jerome of Moravia was either unaware of this rebek, or did not consider it worth mentioning, or classed it among the fiddles with fewer than 5 strings he did not think worthy of consideration. In 1310, 30 years after Jerome, Italian physician, philosopher and astrologer Pietro d’Abano also mentioned the 2 string bowed “rubeba” in his Expositio problematum Aristotelis, but he did not mention the rebec.

Evidence is lacking to say with certainty which reason is most plausible to explain the 12th century mention of the rebek followed by the long silence. Its connection with the rebab, if any at all, is conjectural and lacking evidence.

The rise of the rebec

European rebec in the Catalan Psalter, c. 1050,

often cited as such by modern writers.

However, the evidence suggests this is a vielle.

Right: Detail of a player in the English

manuscript, British Library Arundel 91

(folio 218r), a Passionale (Lives of the Saints)

originating in Canterbury in the first quarter

of the 12th century. This has also been cited

as a rebec but, if its 4 strings are taken literally,

it has to be a vielle, and other features such as

the shape of peg box identify it as such.

The earliest identification of European rebec iconography, as recognised by modern authors, is in the Catalan Psalter, c. 1050 (see images on the right), a few decades before the first appearance of the word rebek in the early 12th century. We have the 3 strings and the piriform (pear shape), so this appears at first to show that the rebec had been in existence across western Europe since the 11th century.

However, the identification of the Catalan Psalter instrument as a rebec is a mistake. The piriform of the rebec looks from the top like one of the shapes of the vielle or medieval fiddle, distinguishable by the rebec having a bowl back and the vielle having a flat back, but such a visual difference is hidden in two dimensional images where only the soundboard is visible. It has therefore been easy for modern authors, seeing a 3 string piriform instrument, to call it a rebec. Corroboration from an accompanying text would settle the matter, but this is very rare in medieval iconography and, as we have seen, there is only one surviving contemporaneous mention of a rebek, which is itself problematic. It is therefore not possible on this basis to say whether the image in the Catalan Psalter is a rebec or a vielle. The same would apply to the similar instrument in British Library Arundel 91 (right), except that closer examination shows it to have 4 strings. If we work on the assumption that rebecs always had 3 strings – and all the available evidence suggests this – then the BL Arundel 91 instrument is a vielle. This identification is itself based on the assumption that the depiction of 4 strings is accurate, since there are only 3 pegs.

There is another visual factor which helps, and may be definitive. A visible feature to distinguish a rebec from a vielle is that only rebecs had crescent-shape pegboxes, whereas vielles had flat peg-boxes, usually rounded, sometimes quadilateral. In terms of bowed instruments, only the rebab/rabab had a bowl back prior to 1300, therefore bowed instruments before 1300 with piriform soundboards that are not rebabs have flat backs, and are therefore not rebecs. On this basis, the instruments above in the Catalan Psalter and BL Arundel 91, dated c. 1050 and c. 1100-1125, must be flat-back vielles.

However, this leaves us with the puzzle of the word rebek appearing in the early 12th century table of Arabic and Latin terms (Paris, Bibliotheque Nationale, Ms. lat. 14754). What did the word then convey? Did it mean the instrument we now associate with the word? If so, why does it not appear in surviving three-dimensional iconography, and why the long gap before its next mention? If rebek did not mean the bowl-back bowed instrument, what did it mean? Evidence is lacking to answer these questions.

When the rebec truly began is a subject of much debate, but 1400 seems a good rough guide, given the iconographical evidence. During the 15th and into the early 16th century, the rebec is regularly seen in paintings of saints, therefore associated with heaven and holiness, and sometimes coupled with the lute, which had the same associations.

The rebec has a bowl body carved from a single, solid piece of wood, scooped and chiselled out to produce a hollow shell, played on the chest or on the shoulder. According to German music theorist Martin Agricola, Musica instrumentalis deudsch, 1529, the rebec had 3 strings, each tuned a fifth apart.

Above: Madonna with angels making music, c. 1500.

Below: The Virgin among angels, Netherlands, 1509.

The rebec hangs tenaciously on

Evidence of the rebec’s royal approval is illustrated in the accounts of King Charles VIII of France, showing that he twice paid for a rebec to be played for him: the 1483 account lists a fee of 30 sol to a rebec player, and in 1490 a fee was paid to a rebec player named Raymond Monnet.

However, its courtly appeal was slowly fading. Despite its association with heaven, its reedy, nasal sound came increasingly to be regarded as rural, more suitable for lower class dances. Perhaps, towards the end of the 15th century, it began to compare unfavourably with the more full-bodied tone of the new viola da braccio (also known as the lira or lyra da braccio). The decline of the rebec was slow and uneven, and it remained popular in English and French royal courts into the 16th century.

No music survives specifically for the rebec. From around 1480–1500 – so by now in the renaissance – we see the rise of music written for individual instruments, most especially for the lute and, in the following century, for the vihuela, guitar, cittern, bandora, orpharion, the consort of viols (viola da gambas in different sizes and therefore pitches playing together) and the broken consort (a mixture of wind, plucked and bowed instruments playing together). With the arrival of the much fuller-sounding renaissance six or seven string viol, and with no music being written for the rebec, one might have thought it would die out completely.

But no. Though there is no surviving music for it, the rebec clearly survived through the renaissance. In his Musica instrumentalis deudsch, 1528, German music theorist Martin Agricola stated that the rebec now had a full consort of soprano, alto, tenor and bass, as had the lute, viol, recorder and crumhorn families. In 1526, English King Henry VIII had three rebecs in his consort for state occasions. French King Louis XIII kept a personal royal rebec player, Lancelot Levasseur, from 1523-1535; and his succeeding son, King Louis XIV, had Jehan Cavalier performing the same function in 1559.

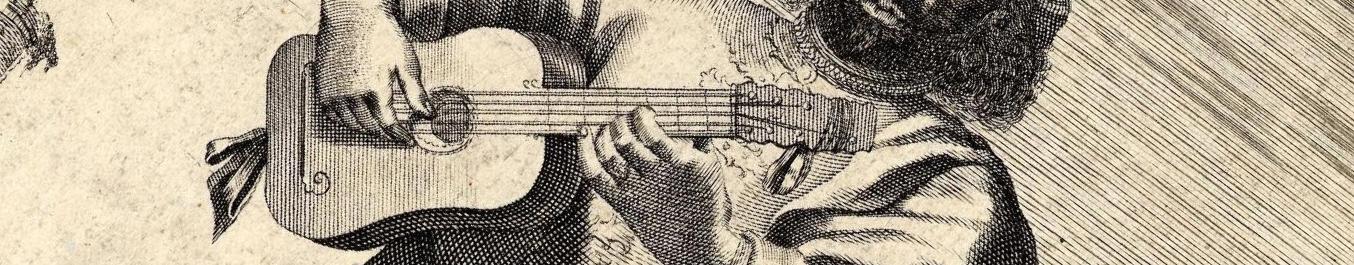

rebec, by the Flemish artist,

Pieter Paul Rubens, 1577-1640.

In William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, c. 1595-96, at the forced wedding of Juliet, which appears to have turned into her funeral as she is apparently dead, Peter asks the musicians to play a piece called Heart’s ease. Shakespeare helpfully gives the musicians joke names to indicate their instruments, including one “Hugh Rebec”.

Proponents of the rebec were fighting a losing battle, especially with the rise of the esteemed violin, which eventually even trumped the much-loved viol family. In 1628 the Parisian authority wanted to make class distinctions clear in who was allowed to do what and where. They passed a law forbidding the playing of high status violins in public houses, allowing only low class rebecs. Over a century later, the rebec was still being tenaciously played in France when a law was passed in Le Guignon in 1742 restricting the “amusement of the people in the streets and the public houses” to the undignified “three stringed rebec”, specifically forbidding the playing of the higher status four stringed violin.

The rebec: old and new knowledge

The rebec, then, has been the subject of much misidentification and confusion for modern players and scholars of early music. It hasn’t helped that some medieval writers used the catch-all term fiddle to denote any bowed instrument, but recent comparative research in iconography – both manuscripts and three dimensional carvings – has brought more clarity about the difference between the rebab or rubeba, the vielle (medieval fiddle) and the rebec, and this has resulted in a necessary questioning of previous repeated assertions, based on assumptions rather than demonstrable evidence.

For modern players of early music, the story of the rebec suggests it to be appropriate for late medieval and renaissance courtly music, lowering its status to a lowly street instrument as musical tastes and fashions changed during the baroque period, before disappearing from sight during the 18th century.

© Ian Pittaway. Not to be reproduced in any form without permission. All rights reserved.