In recent years, a story about a detail in Jheronimus Bosch’s painting of 1495–1505, The Garden of Earthly Delights, has been repeatedly told: that a sinner on the hell panel of the triptych has real music painted on his bottom, only recently discovered. Periodically, articles and videos reappear on social media with a performance of the same attempt to make sense of it, created by Amelia Hamrick in 2014. Is this oft-repeated butt music credible?

In recent years, a story about a detail in Jheronimus Bosch’s painting of 1495–1505, The Garden of Earthly Delights, has been repeatedly told: that a sinner on the hell panel of the triptych has real music painted on his bottom, only recently discovered. Periodically, articles and videos reappear on social media with a performance of the same attempt to make sense of it, created by Amelia Hamrick in 2014. Is this oft-repeated butt music credible?

To put Bosch’s painting in its historical context, a previous article, Performable music in medieval and renaissance art, examined the role of both faux music notation and playable music in medieval and renaissance art. This article explains why the paint on the sinner’s bottom does not represent real music, and why attempts to interpret the ‘music’ are based on erroneous assumptions and misunderstandings. A second article, available here, explains the rich symbolism of The Garden, including the meaning of musicians tortured by their own instruments, silenced by the demons of hell. A third and final article, available here, surveys the musical symbolism in all Bosch’s works, and asks why his depictions of music are always grotesque, associated with sin, punishment and hell.

The claim: Bosch’s “Gregorian notation”

The left panel is the sixth day of creation, before Original Sin brought about the Fall;

the central panel is humanity revelling in their sins;

and the right panel is the payment for those sins in hell.

(As with all pictures, click to see larger in a new window, click in new window to further enlarge.)

In 2013, a Humanities class at Oklahoma Christian University studied The Garden of Earthly Delights, painted 1495–1505 by Jheronimus Bosch (c. 1450–1516) of The Netherlands. One student attending was Amelia Hamrick. In February 2014 she decided to interpret what she took to be genuine music painted on the bottom cheeks of one of Bosch’s sinners in hell. She posted it on her Tumblr page on 11th February 2014.

The ‘music’ has no clef and, without a clef, notes have no definite pitch. She explained on her Tumblr page that she “decided to transcribe it into modern notation, assuming the second line of the staff is C, as is common for chants of this era”. Her short post with soundfile was picked up immediately by the press. In a video recorded for The Oklahoman only 3 days after her Tumblr post, she explained that she “found a guy’s rear end with music written on it in Gregorian notation”, the system of square notes used for Gregorian chant. “As far as we know,” she said, “nobody’s ever actually tried to play this before, and so it hasn’t been heard in 500 years.” To account for it not sounding very musical, she explained, “I think the painter, Jheronimus Bosch, was just putting notes on there. It doesn’t sound like, it’s not a very good Gregorian chant, really. I think he may have just been faking it. But if it does actually sound like some other piece, that would be really interesting, and it’s definitely something to look into, to see if it resembles any other existing work that we know of.”

Two weeks later, she was interviewed by CNN. Her analysis of The Garden of Earthly Delights was: “It’s kind of like a 500 year old Where’s Waldo? poster”. By then, her page and musical interpretation had became an internet and media sensation, inspiring renditions for choir, heavy metal band, and an arrangement for lute, harp, and vielle à roue (hurdy gurdy).

The story has now done the rounds multiple times on Facebook, Twitter, and other social media, having been covered in news stories by The Oklahoman, Edmond Outlook, Public Radio International, Gizmodo (now removed), Cracked, Dangerous Minds, Open Culture, medievalists.net, artnet news, Realm of History (now removed), The Daily Mail, The Guardian, Classic FM, and Thomann. Amelia added to her Tumblr page that she “threw this together in like 30 minutes at 1 in the morning … I still can’t believe this took off like it did this is crazy???”

Edmond Outlook asked the key question of this article: “did Bosch intend this now-internationally-famous song to ever be played?” As I will make clear, the answer is a definitive no. I’ll need to convince you of cogent reasons why Amelia Hamrick and, as we will see, Vox Vulgaris, Gregorio Paniagua and Atrium Musicae, and art historians J. Lennenberg and Laurinda S. Dixon, were all mistaken. To understand why, we need to understand what forms of music notation in c. 1500 did and did not look like, recognise the role of music in medieval and renaissance paintings generally (discussed in more detail in a previous article, available here), and Bosch’s message about music and musicians conveyed in The Garden of Earthly Delights and his other works. Individually and collectively, all these factors point to the same conclusion: since Bosch painted only the appearance of music, this ‘butt music’ was never intended to be read and played.

4 claims examined

Claim 1: Amelia Hamrick ‘discovered’ the butt music

In their story of April 2014, Edmond Outlook asked, “is it true that Amelia is the first to ever play Bosch’s song?” To answer, they quoted Oklahoma Christian University music professor, John Fletcher: “This is a well-documented painting. I thought someone might come forward with doctorial research, but interestingly, nothing has surfaced in the weeks since this has been publicised”. If this is an accurate quote it is odd, as it suggests that a music professor would take a claim by a student on trust that no one in 500 years had previously noticed or commented on the ‘butt music’, making a statement to the effect that he has not investigated this himself, and apparently not helped her develop her academic rigour by examining papers on the subject for which she claims originality, instead expecting someone to voluntarily emerge as a result of publicity in the non-academic, non-specialist popular press. It appears that neither the music professor of Oklahoma Christian University, nor Amelia Hamrick, nor the reporting press checked Bosch scholarship to date or, more critically, consulted a specialist in early music notation. Therefore Edmond Outlook spoke for them all in stating that Amelia “can certainly take credit for bringing this posterior story to the forefront”.

It isn’t true. 11 years earlier, in 2003, Swedish players of medieval music Vox Vulgaris released their album, The Shape of Medieval Music to Come, the last track of which is The Garden of Earthly Delights. The album’s notes claim, “Hieronymous Bosch has long been known as a painter. Vox Vulgaris are the first to consider him a composer. Almost 500 years after his death, we offer a first performance of De jordiska fröjdernas Paradis (The Garden of Earthly Delights), a musical piece Bosch annotated on a man’s butt in his triptych by the same name.”

It isn’t true. 11 years earlier, in 2003, Swedish players of medieval music Vox Vulgaris released their album, The Shape of Medieval Music to Come, the last track of which is The Garden of Earthly Delights. The album’s notes claim, “Hieronymous Bosch has long been known as a painter. Vox Vulgaris are the first to consider him a composer. Almost 500 years after his death, we offer a first performance of De jordiska fröjdernas Paradis (The Garden of Earthly Delights), a musical piece Bosch annotated on a man’s butt in his triptych by the same name.”

The assertion by Vox Vulgaris that they were “the first to consider [Bosch] a composer” isn’t true, either. In 1978, 25 years before Vox Vulgaris, Atrium Musicae, directed by Gregorio Paniagua, recorded Introitus, Obstinato I – Organa as track 1 of their LP, Codex Gluteo (Buttock Manuscript), consisting of organum over the notes they understood to be on the sinner’s bottom.

Neither were Gregorio Paniagua and Atrium Musicae the first. On the web page of Edmond Outlook that carries the story of Amelia Hamrick’s butt music, Laurinda S. Dixon, Professor in the Department of Art and Music Histories, Syracuse University, posted an angry response in June 2015, a year after the story was reported. She addressed Amelia directly (though this is a news site, not Amelia’s personal page): “To Amelia Hamrick: You are not the first to transcribe the “butt music” of Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights, which you have taken credit for in the media and on the web. As you perhaps know, J. Lenneberg, ‘Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights: Some Musicological Considerations’, Gazette des Beaux-Arts (1961), and myself, Laurinda Dixon, Alchemical Imagery in Bosch’s Garden of Delights (UMI: 1981), both transcribed it, and also noted the “devil’s interval” and various other satanic compositional devices. Your “discovery” has been common knowledge among art historians for over 50 years. Either you did not do your research, or you plagiarized our work. Unacceptable in either case …” Edmond Outlook have now removed Professor Dixon’s comment from their page.

Neither were Gregorio Paniagua and Atrium Musicae the first. On the web page of Edmond Outlook that carries the story of Amelia Hamrick’s butt music, Laurinda S. Dixon, Professor in the Department of Art and Music Histories, Syracuse University, posted an angry response in June 2015, a year after the story was reported. She addressed Amelia directly (though this is a news site, not Amelia’s personal page): “To Amelia Hamrick: You are not the first to transcribe the “butt music” of Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights, which you have taken credit for in the media and on the web. As you perhaps know, J. Lenneberg, ‘Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights: Some Musicological Considerations’, Gazette des Beaux-Arts (1961), and myself, Laurinda Dixon, Alchemical Imagery in Bosch’s Garden of Delights (UMI: 1981), both transcribed it, and also noted the “devil’s interval” and various other satanic compositional devices. Your “discovery” has been common knowledge among art historians for over 50 years. Either you did not do your research, or you plagiarized our work. Unacceptable in either case …” Edmond Outlook have now removed Professor Dixon’s comment from their page.

Claim 2: The pitch of the ‘music’

For music notation to be meaningful to anyone who relies on the written page alone, there needs to be a clear indication of pitch and rhythm.

In the 9th to 11th centuries, written music in its various forms was an imprecise aide-mémoire for singers who already knew the melody. The daseian (or dasian) notation of the anonymous 9th century Musica enchiriadis and its companion volume Schola enchiriadis, for example, shows precise pitch relationships but does not notate rhythm. Another of the earliest known forms of European music notation originated in the 9th and 10th centuries in the Benedictine monastery of Saint Gall (Sankt Gallen) near Lake Constance, in (what is now) Switzerland. These early neumes (note shapes or figures of movement) give the pitch direction of the melody but, since this notation lacks ledger lines, there is no precise pitch. This means that music-making from such sources today can only ever be conjectural.

(Sankt Gallen), Switzerland, dated c. 1150. It measures a narrow 25.5cm x 8cm so that it can be

easily carried in one hand by a singing monk, and shows early neumes without precise pitch.

(This image of St. Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. Sang. 360, is licensed from e-codices.)

Through the 12th and 13th centuries a more accurate system of neumes was developed. By the middle of the 13th century both pitch and rhythm were evident to the point where the scribe’s intentions were a matter of reading the page rather than jogging the memory. The system now known as square notation – or, to be more precise, square notation as described in the mid-13th century by Franco of Cologne, now known as Franconian notation – is seen in such English songs as Sumer is icumen in, c. 1250, and bryd one brere, c. 1290–1320, and tells the singer all the important information.

Franconian notation was a development of the square notation of Gregorian chant, in which pitch is clearly indicated but mensuration – note duration and therefore rhythm – is not. Amelia Hamrick’s interpretation of Bosch’s ‘butt music’ is based on her assumption that it is Gregorian chant and that “the second line of the staff [from the top] is C, as is common for chants of this era”.

This interpretation is false for three reasons: an assumption about the type of clef; an assumption about the position of the clef; and an assumption about the type of notation. Let’s examine these in turn.

First, the assumption about the type of clef. Musical pitch was indicated by either a C clef, an F clef or, by the time of Bosch’s painting in c. 1500, a G clef, as we see below. This means Amelia’s assumption of a C rather than an F or G clef is unreliable, so on this basis pitch cannot be determined.

The excerpts above are from a book of Gregorian chant held by the Miller Nichols Library, University of Missouri-Kansas City. It is compiled from plainchant manuscripts of the 10th to the 16th century and is now bound in a single volume. We see four line staves ruled in red: top left, Kyrie with an F clef on the second line up; top right, Alleluia with a C clef on the second line down (where Amelia Hamrick wrongly assumed all C clefs would be); at the bottom, an antiphon with an F clef on the second line down, moving to the second line up on the second stave.

Above are five voices on Kyrie Eleison (Lord have mercy) from the Mass, Virgo Parens Christi, by Jacques Barbireau (c.1420–1491), written in white notation, a further development of the black square notation seen above, from an early 16th century manuscript now in the Vatican (Capp. Sist. 160, folios 2v-3r). Left top to bottom then right top to bottom, we see five line staves with: a G clef on the second line up; a C clef on the middle line; an F clef on the middle line; a C clef on the second line up; and a C clef on the middle line. These floating clefs have developed into today’s fixed clefs: G for the treble clef, F for the bass clef, C for the alto clef.

Above are five voices on Kyrie Eleison (Lord have mercy) from the Mass, Virgo Parens Christi, by Jacques Barbireau (c.1420–1491), written in white notation, a further development of the black square notation seen above, from an early 16th century manuscript now in the Vatican (Capp. Sist. 160, folios 2v-3r). Left top to bottom then right top to bottom, we see five line staves with: a G clef on the second line up; a C clef on the middle line; an F clef on the middle line; a C clef on the second line up; and a C clef on the middle line. These floating clefs have developed into today’s fixed clefs: G for the treble clef, F for the bass clef, C for the alto clef.

The second error in Amelia Hamrick’s analysis is an assumption about the position of the clef. Whereas in modern music we have a standard staff or stave of five lines with a fixed treble clef – a G clef – always indicating G on the second line up, the staff in Bosch’s day had a variable number of lines, most commonly four, and the C, F or G clef could appear on any line – indeed, sometimes the clef changed position within a single piece of music, as we see above.

The Mellon Chansonnier was probably written in Naples in the 1470s at the Aragonese court, and is contemporaneous with Bosch. In En soustenant vostre querelle by Antoine Busnois, folio 2v, below, we see again that the C clef is moveable, appearing first on the second line up, then on the bottom line, to keep the melody within the ambit of the five line staff.

This variability was used to maintain a principle of written music: the type of clef, the position of the clef, and the number of lines on a staff were all used to keep the melody within the range of the staff, so the clef type, clef position and number of lines depended on the pitch and range of the melody. In modern music, with a fixed clef and fixed number of staff lines, notes above and below the staff have ledger lines to indicate their pitch, a device neither available nor necessary for writers of square notation.

Claim 3: This is Gregorian notation

So we see there is an unsafe assumption about the type of clef, and an unsafe assumption about the position of the clef. The third reason that the interpretation of this ‘music’ as Gregorian chant is false is the most basic: it isn’t Gregorian chant. Even a cursory comparison of the ‘music’ in the painting with real chant notation shows that they are different.

Below: Faux music notation in Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights,

on the sinner’s bottom and in the book beneath the lute, with notes shown as strokes,

not the squares and diamonds of Gregorian notation.

This doesn’t mean that Bosch painted Gregorian notation badly, or that he painted an imaginary form of music: this is an imitation of Strichnotation.

Strichnotation – stroke notation – is an imprecise form of written music that gives very little or no indication of rhythm, with a staff which gives an indication of the pitch of notes relative to one another, but no indication of the actual pitch, which makes any interpretation guesswork. If, for example, two adjacent notes are taken to be C and D, we have a step difference of one tone, but if those notes are taken to be B and C, then we have a step of one semitone. When this problem is multiplied throughout a piece of music, added to the lack of written rhythm, we see why any one interpretation of Strichnotation may be radically different from another, with no way of knowing which is more correct. This, then, is not a system of notation, as it is not systematic: it is an aide-mémoire for singers who already know the melody, used in several sources in Bosch’s lifetime and in his region of the world.

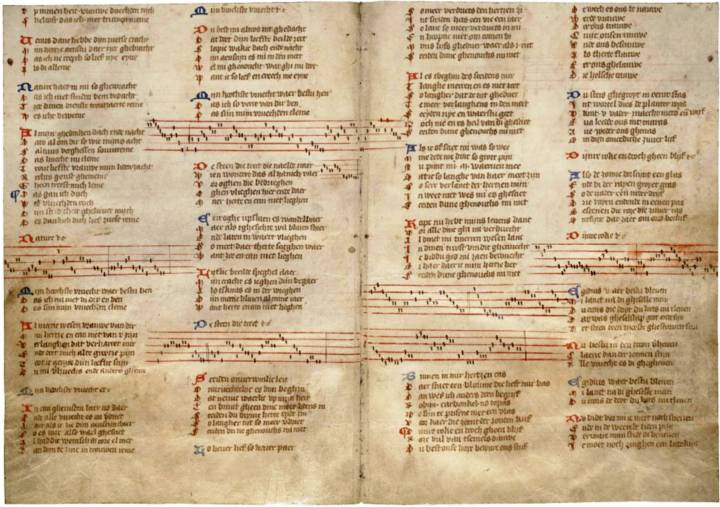

One of the most important sources for this way of writing music is the oldest surviving collection of Flemish songs, written in the cultural metropolis of Bruges in Flemish Belgium (now in the Koninklijke Bibliotheek in The Hague as KW 79 K 10). The Gruuthuse manuscript includes 7 prayers, 18 poems, and 147 songs in Strichnotation. The earliest entries are c. 1395, the latest c. 1410 (dated shortly before Bosch’s birth in c. 1450), and none of the songs are found in any other source. As we see on folios 27v–28r below, the pages are carefully laid out but do not include elaborate decoration. This indicates a working book used by a musician or musicians, not a book commissioned by a wealthy patron. The chief subject of the 147 songs is love in its various forms: love for the Virgin Mary and God; requited and unrequited romantic love; love for one’s home city and for friends. Unlike the fin’amor – refined love – of the troubadours and trouvères, in which the female love object is distant, perfect, unreachable, and often of a higher social status, the Gruuthuse songs emphasise lovers’ equality.

It was common practice in medieval manuscripts and in renaissance prints to establish the relationship between words and music in the first verse, each syllable underneath its respective note or notes. Since the first verse clarified this relationship, the words of verse two onwards were typically written or printed as a block, separate from the music. We see above in folios 27v-28r and in the detail below that in the Gruuthuse manuscript the music notation is entirely separate from the text, so the relationship between text and music is not clear to the reader. It is therefore the case that, just as Strichnotation only works for those already familiar with the music, the Gruuthuse manuscript only works for those already familiar with the songs.

Below: Bosch’s imitation of Strichnotation in his Garden of Earthly Delights.

As we see above, it is not the case that Bosch’s ‘music’ is separate from the song words, but that words are completely absent. Furthermore, the ‘notes’ are placed randomly, some directly above others, and the last line on the sinner’s bottom is a three line staff. This means that just as we can clearly establish that this is not Gregorian chant, it is not real Strichnotation, either, for reasons further explained in the second article (available here), which explores the meaning of the painting, and in the third article (available here), which surveys all of Bosch’s musical imagery, including other Bosch works with faux Strichnotation.

So when Amelia Hamrick stated, “it’s not a very good Gregorian chant, really”, she didn’t understand that this is not Gregorian chant, but she did recognise that the result of her work doesn’t give a musical result: “I think the painter, Jheronimous Bosch, was just putting notes on there, I think he may have just been faking it.”

The correction of suppositions about the assumed type of clef, its assumed position and assumed type of notation reveal the impossibility of determining pitch in this imitation of music, which in turn raises the question of Laurinda Dixon’s claim, cited above, to have “noted the “devil’s interval” and various other satanic compositional devices” in this painting. The devil’s interval or diabolus in musica – devil in music – is now the colloquial name for a tritone, the interval of three whole tones, a diminished fifth or augmented fourth, which occurs in the interval B–f or f–b. It sounds like this:

There is as much modern mythology about diabolus in musica as there is about Bosch’s butt music. Claims abound on the internet that the medieval church named it and banned it because it was considered ungodly, or because it was hard to sing, none of which is true. There is no evidence for the term diabolus in musica before the early 18th century, and even then it did not apply exclusively to the tritone. In his Harmonologia musica, 1702, German composer Andreas Werckmeister used diabolus in musica to mean both the tritone and semitone clashes, such as between the same note with and without an accidental, e.g. F natural against F sharp, and “mi contra fa”, the clash between the third and fourth degrees of a major scale, e.g. E against F in C major. Werckmeister cites diabolus in musica as a term used by “the old authorities”, but he gives no evidence or reference for this vague assertion. Similarly, in his Musique de table, 1733, German composer Georg Philipp Telemann described “mi against fa” as an interval called “Satan in music” by “the ancients” – once again with a vague and unsubstantiated alleged history, and not even referring to the tritone. In the early 18th century, then, diabolus in musica simply meant intervals played together which grate on the ear. Vague references to “the ancients” are not verifiable and can therefore be dismissed. There is no evidence of the term or the concept of diabolus in musica before 1702.

The idea of the devil in music as a term Bosch would have understood is therefore not only a misapprehension, it is an anachronism. Yet still this modern error has crept into reference works. The Oxford Dictionary of Music, for example, perpetuates the diabolus mythology by stating that “in medieval times its use was prohibited.” It wasn’t: it wasn’t even an idea then. In his Micrologus, c. 1026, Guido of Arezzo included B flat as the only accidental in the otherwise natural notes of the medieval gamut or range of notes, and the use of a flattened B against an F smoothes the harmonic interval and removes the tritone, but any notion that this was because it was considered Satanic is a modern fantasy. For example, Pérotin (fl. c. 1200), part of the influential Notre Dame school of polyphony, used a deliberate tritone in the opening notes of his three voice Alleluya / Posui adiutorium. (You can hear the tritone in the opening notes by clicking here.) Furthermore, as Carl Parrish (1957) observes, there are “numerous instances of tritone skips in Gregorian chant.”

To summarise, Laurinda Dixon’s assertion that she “noted the “devil’s interval” and various other satanic compositional devices” in the ‘butt music’ is predicated on:

1. the pitch of the notes being identifiable, to identify the tritone – they’re not;

2. the painted backside having real music on it – it doesn’t;

3. there being such a thing as the devil’s interval in c. 1500, known to Bosch and employed by him in his painting – there wasn’t.

Claim 4: Bosch’s painting is like Where’s Waldo?

In all the articles, in all the regular rounds of online activity perpetuating the modern myth of Bosch’s ‘butt music’, the adjacent music book under the lute is ignored. My impression is that this isn’t of interest because it isn’t ‘funny’ and is therefore disregarded, whereas ‘butt music’ apparently has comedic value. Not only is the ‘music’ in the book ignored, the fact that Bosch painted the same kind of faux Strichnotation in three other works – his paintings The Haywain and The Last Judgement, and his drawing, The Singers in the Egg – is either ignored or unknown by the repeaters of the mythology. (All three works are described and shown in the last article in this series, available here.)

In all the articles, in all the regular rounds of online activity perpetuating the modern myth of Bosch’s ‘butt music’, the adjacent music book under the lute is ignored. My impression is that this isn’t of interest because it isn’t ‘funny’ and is therefore disregarded, whereas ‘butt music’ apparently has comedic value. Not only is the ‘music’ in the book ignored, the fact that Bosch painted the same kind of faux Strichnotation in three other works – his paintings The Haywain and The Last Judgement, and his drawing, The Singers in the Egg – is either ignored or unknown by the repeaters of the mythology. (All three works are described and shown in the last article in this series, available here.)

It follows that, in this cherry-picking of a detail out of context, no care is taken over comprehending the meaning of the ‘music’ in its historical framework. The lack of contextual understanding is summed up in Amelia Hamrick’s analysis of the painting: “It’s kind of like a 500 year old Where’s Waldo? poster.”

I want to emphasise that this article is not intended to be in any way a personal critique of the young student, Amelia Hamrick. Having posted the music online, she found herself quickly at the centre of media interest by chance, without seeking it or expecting it. Through lack of knowledge, she made erroneous assumptions about the painting and based her interpretation of the faux music on those errors. We all have preconceptions due to limited knowledge which we later discover then correct. This is both fundamentally human and an important part of the learning process. Fortunately, most of us, most of the time, do this privately, not in the public eye. Unfortunately, the repeated articles which re-circulate and perpetuate the story are pieces of popular culture, not academic analyses, and they could not be expected to have the specialist knowledge to ask the pertinent questions about the veracity of the ‘find’. If the press reporting is to be believed, the staff of Oklahoma Christian University, having seen the initial publicity with their student at the centre, were passive in their response, waiting for others to come forward. If that is the case, then they missed a golden opportunity to help their student gain a valuable lesson in the importance of academic rigour.

Jheronimus Bosch and the music of hell. Part 2/3: The Garden of Earthly Delights

Having established in part 1 that the music isn’t real, in part 2 we examine the whole triptych and its symbolism of sin. We will see Bosch’s preaching with paint, with instruments of music in this world turned into instruments of torture in the next, and understand the faux notation or ‘butt music’ in that context. To go to part 2, click here.

© Ian Pittaway. Not to be reproduced in any form without permission. All rights reserved.

Bibliography

As well as the references to press coverage of Amelia Hamrick’s ‘butt music’ and recorded renditions of it, links for which are in blue text in the article above, the following works were also consulted:

Borchert, Till-Holger (2016) Bosch in Detail. Antwerp: Ludion.

Bosch Research and Conservation Project (2016) Hieronymous Bosch. Painter and Draughtsman. Catalogue Raisonné. New Haven: Mercatorfonds / Yale University Press.

Cowderoy, Alan (2008) The Mellon Chansonnier. Available online by clicking here.

Erdmann, Robert G., et al. (2016) Bosch Project. Available online by clicking here.

Fischer, Stefan (2013) Jheronimus Bosch: The Complete Works. Köln: Taschen.

Gibson, Walter S. (1983) Reviewed Works: Alchemical Imagery in Bosch’s Garden of Delight by Laurinda S. Dixon; Hieronimus Bosch: The Temptation of Saint Anthony by Anne F. Francis. Renaissance Quarterly, Vol. 36, No. 1 (Spring 1983), pp. 112-115. Available online by clicking here.

Gibson, Walter S. (2003) The Strawberries of Hieronymus Bosch. Cleveland Studies in the History of Art, Vol. 8, pp. 24-33. Available online by clicking here.

Ilsink, Matthijs & Koldeweij, Jos (2016) Hieronymous Bosch: Visions of Genius. New Haven: Mercatorfonds / Yale University Press.

Kelly, Thomas Forrest (2015) Capturing Music: the story of notation. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Kennedy, Michael; Kennedy, Joyce; & Rutherford-Johnson, Tim (2013) Oxford Dictionary of Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Koninklijke Bibliotheek: Nationale Bibliotheek van Nederland (National Library of The Netherlands) (undated) Het Gruuthusehandschrift. Available online by clicking here.

Koninklijke Bibliotheek: Nationale Bibliotheek van Nederland (National Library of The Netherlands) (undated) Inhoudsopgave van het Gruuthusehandschrift. Available online by clicking here.

Marijnissen, R. H. & Ruyffelaere, P. (1987) Bosch. Antwerp: Tabard Press.

Maroto, Pilar Silvo (ed.) (2016) Bosch. The 5th Centenary Exhibition. London: Thames & Hudson.

Meagher, Jennifer (2009) Food and Drink in European Painting, 1400–1800. Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Available online by clicking here.

Parrish, Carl (1957) The Notation of Medieval Music. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Schulter, Margo (2000) Hexachords, solmization, and musica ficta. Available online by clicking here.

University of Missouri-Kansas City (2021) The Book of Gregorian Chant. Available online by clicking here.

Vojvoda, Rozana and Paranko, Rostyslav (undated) Body Language. Available online by clicking here.

Williams, Gordon (1994) A Dictionary of Sexual Language and Imagery in Shakespearean and Stuart Literature: Volume II G-P. London and Atlantic Highlands, NJ: Athlone Press.

There is a second example of “butt music” in Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights: Hell. If, as the Book of Revelations has it, pipers are to be heard no more in Babylon, they are certainly to be heard in other places. The fellow holding up the giant shawm (to the right of the hurdy gurdy) plays what can only be a duct flute (flageolet or recorder) in a most unusual manner. Doubtless he is sounding a bum note or two! Perhaps he is a music critic! In the event, this vulgar instrument is cylindrical and only two finger holes are visible, the rest being ‘hidden’ (or to follow)!

Hello, Nicholas, and thank you for your excellent and informative recorder page (at https://www.recorderhomepage.net/ for anyone else reading).

Thank you too for your comment. In the second Bosch article https://earlymusicmuse.com/bosch2/ I analyse all the musical features of The Garden, and raise the question of whether the instrument inserted in the bumbard-carrier’s anal fistula is a recorder, transverse flute or enlarged fife. I hadn’t come across the Revelations passage about pipers being heard no more in Babylon, so I’m now intrigued about whether Bosch was implicitly referencing this. Thanks, Nicholas, I will add that to the second article and credit you. When examining the painting, I did wonder myself how many finger holes were hidden from view inside the musical sinner. Yikes!

All the best.

Ian

Fascinating read, Ian and I can’t wait to read parts 2 and 3!

Thank you!

Andrew Cummings

Worcester, Massachusetts, USA

Thank you, Andrew.

i was wondering if the notes were meant to represent the screams of the damned? a sort of hellish choir.

Hello, Jonathan.

There is nothing in the painting to indicate that. That would require the ‘notes’ to be meaningful – as I explain in the article above, this is faux music, painted to look like Strichnotation, but meaningless musically. I explain in detail how this fits in with Bosch’s overall artistic schema under the subheading ‘The book of music and butt music’ in this article: https://earlymusicmuse.com/bosch2/

All the best.

Ian