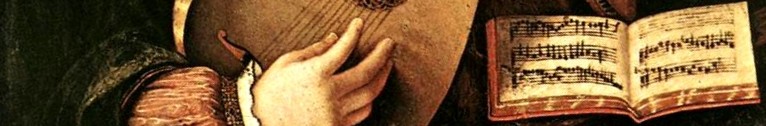

Part 1 brought together the written, iconographical and material evidence for the characteristics of plectrums used to play the gittern, lute, psaltery, citole and cetra, made from quills, gut strings, metal, bone, and ivory.

In part 2 we examine the practical evidence for medieval plectrum technique. Iconography is presented to demonstrate medieval ways of holding a plectrum; suggestions are made for easy accompaniment of monophonic melodies; the myth that plectrum instruments could not play polyphony is disproven; and evidence is presented for an intermediate stage in the 15th century between playing with a plectrum and playing with fingertips, using both simultaneously. Finally, we answer the question: were plectrums always used to play medieval plucked chordophones?

This article includes 7 videos to illustrate medieval and early renaissance plectrum technique, beginning with citole and gittern playing an untitled polyphonic instrumental – probably a ductia – from British Library Harley 978, folio 8v-9r, c. 1261–65.

This is a revised version of the article originally published in January 2023, now with additional information, more examples of iconography, and a new illustrative video.