This is the fourth in a series of eight articles about the 71 stone and wood carvings of musicians created between 1330 and 1390 in Beverley Minster, a church in the East Riding of Yorkshire. Since Beverley Minster has more iconography of medieval musicians than any other surviving historical site, these articles are a survey of the musical life of 14th century England.

Having given the Minster’s history in the first article, described the medieval musicians of the arcades and triforium in the second article and those on the walls either side of the nave in the third article, here all the outstanding medieval stone and wood carvings are explored in the remaining parts of the church. We will see 14th century carvings of musicians playing bagpipes, hunting horn, vielles (medieval fiddles), harps, portative organs, psaltery, oliphants, and nakers. These carvings raise questions about: the history of the influential de Percy family from the Norman conquest to the English Civil War; the royal and military practice of blowing elephant horns; and the pre-eminence for medieval musicians of the fiddle, bagpipe, harp and portative organ.

Above we see a map of Beverley Minster with locations marked. In this article, we will describe the minstrels of the tomb of the two sisters, the Percy tomb, reredos, Saint Katherine’s chapel, and the south transept.

For a complete list of all the 14th century minstrels in the Minster, go to the foot of the article under the heading, Beverley Minster floor plan and instrument inventory.

My intention in this series of articles is to briefly describe every medieval representation of a musical instrument in the Minster, giving more focus where there are particularly indicative, interesting, or unusual details on the carvings. Blue text is a link to a full article about the instrument or other significant topic.

The tomb of the two sisters

(As with all pictures, click to see larger in a new window, click in new window to further enlarge.)

In the nave, a few steps away from the south wall, is a 14th century tomb canopy, created c. 1340-70, which is not now in its original position. It is seen above left from the vantage point facing the south wall, with the north wall behind us, and above right with the south wall behind us. Since at least the early 17th century, it has been known as the maidens’ tomb or the two sisters’ tomb, the tradition being that it was for two unwed daughters of an 8th century Saxon earl and nobleman named Puch, whose wife was miraculously cured by Saint John of Beverley of a lingering illness which rendered her bed-ridden. The original location of the canopy and the real identity of the inhabitant(s) of its now-missing tomb are not known.

We see above that its four internal corners have downward-facing shafts which stop short, below which the tomb chest would have been housed. At the bottom of each of the four shafts is a face whose identities are unknown, shown below.

(As with all pictures, click to see larger in a new window; click in the new window to further enlarge.)

The ornately decorated tomb has two musical features, both on the north side. Below we see three views of a stone carved bagpiper. The top photograph shows the small sideways figure centre left, in the context of the tomb. Bottom left is a closer view. Bottom right, the bagpiper is turned 90 degrees so he is upright. Like some other bagpipes in the Minster, this instrument is without a drone stock. Such bagpipes are described in some detail in the second article.

(As with all pictures, click to see larger in a new window, click in the new window to further enlarge.)

The bagpiper is on the left side of the tomb. On the right is a man holding a hunting spear and blowing a hunting horn, shown below left in context and in detail below right. This figure was the model for reviving the badly broken figure in bay D of the north wall by John Percy Baker, a mason who worked on the Minster’s minstrels between 1895 and 1912, reuniting broken parts and making new parts where pieces were missing. The monumental task Mr. Baker was faced with is described in the first article; the broken horn-blower on the north wall is described in the third article.

The Percy tomb

In the east of the church is a highly ornate canopy over a tomb of a member of the Percy family, shown above left from the north side. The photograph above right is taken from the south side, to the right of which is the western face of the reredos or altar screen, made in 1825-26 by the Minster’s master mason, William Comins, to replace the western face of the reredos destroyed between 1547 and 1553 during the reign of Edward VI, ultra-Protestant proto-Puritan son of Henry VIII.

Some historians date the carving of the Percy tomb to between the late 1330s and early 1340s, others to between 1340 and 1347. The most likely identity of the occupant is Lady Eleanor de Neville Percy, who died in 1328. Lady Eleanor was the widow of Henry Percy, the first Lord Percy of Alnwick, who died in 1314. The Percys were the most powerful noble family in northern England, as the tomb itself testifies, being in a position of prominence and importance, on the left of the altar, bearing the arms of Edward III, King of England from 1327 until his death in 1377.

Norman knight William de Percy was the first of this family from Percy-en-Auge to live in England. He moved to Spofforth, Yorkshire, in December 1067, the year after the victory of William, Duke of Normandy, over Anglo-Saxon King Harold Godwinson. In England, William de Percy received his reward for services to William the Conqueror by being made the first Baron de Percy, with a vast gift of land. His descendents were to be barons, lords, earls and dukes. When, in the 12th century, his descendent Agnes de Percy was betrothed to Joscelin of Louvain, Joscelin settled in England to marry her and took the Percy family name. Their descendants were made the Earls of Northumberland and so, through their feudal position, ownership of land and connection to the royal court, the Percys played a prominent role in the life of Northumberland and Yorkshire.

Percy descendents of note include Henry Percy IV, made the first Earl of Northumberland by Richard II in 1377, and his son, Henry Percy V, otherwise known as Harry and killed in battle at Shrewsbury, known to posterity as Hotspur in William Shakespeare’s Henry IV. The second Earl fought for the Lancastrians (Tudors) in the Wars of the Roses, while the third and forth fought for the Yorkists (Plantagenets). The sixth Earl was to marry Anne Boleyn before Henry VIII decided she was his. The eighth and ninth Earls were on the losing side of the conflict between the old Catholic faith and the new Anglican religion, and thus they were sent to the Tower of London, while the tenth Earl fought on the side of King Charles I in the English Civil War.

The Percy tomb is highly ornate, with decorative details of the enthroned Christ with angels; flora, leaves and vines; heraldic shields; knights; and angels, some of them musical. The tomb is largely intact except for three details: the passage of time has removed all but the final vestiges of paint from the monument, which was once a mass of colour; once again the iconoclasts have smashed some of the figures, leaving some heads, arms and musical instruments missing; and it once housed a tomb chest of dark stone topped with a brass image of its inhabitant, now lost. This was removed in 1824 to return the monument to its supposed original state, in the belief that the tomb itself was a later addition. Since tomb canopies are intended to house tomb chests, it is now certain that the removed stone tomb was, after all, original.

(As with all pictures, click to see larger in a new window, click in new window to further enlarge.)

Musical angels decorate the north side of the Percy tomb. Above left is an angel singing to a 5 string vielle or medieval fiddle. (There are 4 remaining strings past the bow, but we see 5 strings on the string-holder.) The appearance of the instrument above centre and right is curious. Its shape and playing position indicate a 3 string fiddle, but its small size is unusual, though not unknown. We would not expect to see the trefoil on the tail end beyond the bridge, nor would we usually expect a decorative head carved on a fiddle, though that isn’t impossible, and we certainly wouldn’t expect to see it apparently plucked with a huge plectrum, rather too substantial for an instrument of this size. Perhaps the apparent plectrum is the remains of a broken bow, but the playing angle of the bow to the strings is unrealistic. The hand positions certainly indicate a fiddler, so the best solution I can find for this mystery is to tentatively suggest that this tiny fiddle, which is of slightly lighter stone, is a John Baker replacement, as the angel’s head also appears to be, and that on the original fiddle the placement of the bow, most of which is now missing so it looks more like a plectrum, was more realistic.

(As with all pictures, click to see larger in a new window, click in new window to further enlarge.)

On the south side of the Percy tomb are two musical angels, as we see in context above left. On the right arch, second figure down, is a harp player, shown above right. On the left arch, second figure down, is a portative organ (organetto or organino) player, shown below from two angles.

On the inside of the canopy are three groups of angels, facing down as if from heaven, as we see below.

Working from the left to the right group of angels, the first of these groups (below) consists of a psaltery player (top left); a singing portative organ player (top right); and an angel who cannot be positively identified as a musician (bottom) and so is not included in the total number.

In the central group (below) there are no instruments, the hand positions do not definitely indicate instruments, and the mouths are not open to indicate singing, so this group has not been included in the number of extant or missing instruments in the Minster.

(As with all pictures, click to see larger in a new window, click in new window to further enlarge.)

The group on the right of the roof (below) consists of a harp player with a harp bag (top); a figure which has been destroyed (left); and a third angel with raised hands and no instrument (bottom). Assuming visual symmetry between the groups of angels on the left of the canopy and those on the right, the destroyed figure is presumed to have been a musician since the group on the other side has two musical angels.

To the left of the tomb on the north side are two late 19th or early 20th century statues (above): Saint Cecilia, patron saint of musicians, playing the portative organ, and King David playing the harp. They each stand on a corbel, a projection on a wall to support a structure above it. King David’s corbel has two carved figures, representing Saint John of Beverley and King Athelstan, both important figures in the history of the Minster; Saint Cecilia’s corbel has a characteristically 14th century piper, his bagpipe with a single drone and flat-faced chanter, as we see below. A striking detail on this bagpipe, but not on others in the Minster, is that the instrument’s animal origins are plainly visible. Modern bagpipes are made from synthetic materials, but in the past they were made from the entire pelt of a goat, sheep, cow or dog, and sometimes the physical features of the animal would be preserved in the final instrument, as with the pig here.

To the right of the tomb on the south side, as we see on the right, is a five string fiddle or vielle player hanging downwards and looking towards the altar. This figure, situated above the left side of the western face of the reredos or altar screen, is almost at the same height as the adjacent Percy tomb and is not easy to see without a zoom lens.

This fiddle is the same design as in bay F (described and shown in the third article) and on column 9 of the arcades (in the second article), except that the bay F instrument has a bourdon and the other two do not. Such a fiddle design is widely attested in other medieval iconography. Since all 5 strings here are on the fingerboard, without a lateral bourdon drone string to be plucked or bowed, this fiddle would have been tuned g’ – d’– g – G – d according to the testimony of Dominican friar and music theorist, Jerome of Moravia, in his Tractatus de Musica, c. 1280. Though Jerome doesn’t mention strings paired as courses, it is likely that this would have been 5 strings in 4 courses with an octave double course g/G, a tuning of g’ – d’– g/G – d.

The reredos

When the 11 year old King Edward VI succeeded in 1547 after the death of his father, Henry VIII, he, his Council, his Protectorate, and the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer, enthusiastically hastened Protestant reform. There followed a campaign to rid national life of any signs of Catholicism, including Catholic iconography. In this wave of iconoclasm to remove ‘idolatrous’ images, the west side of the altar screen or reredos was removed, replaced in 1825-26.

The east side of the reredos (above) was created in the late 1330s or early 1340s and remains largely intact, but with some damage. The original colour and gilding is gone, but the canopy is still profusely decorated on the outside with flora and figures of angels and humans. Below we see some of the cornice, with its repeating motifs of foliage and angels and, second from the left, Mary suckling Jesus.

Bottom left is a statue of Mary made during the work of the late 19th or early 20th century, placed on a 14th century decorated corbel, surrounded by intricate carvings of flowers, foliage and heads, and decorated on both sides and above with roses. Since the Virgin Mary as a rose is a long-established Marian theme, this was the evidence modern masons needed to fill the gap with a statue of the Virgin. The foliage represents the natural shortness of time we have in the world and, therefore, the need to live a sinless Christian life for the sake of the eternal soul.

Bottom right is a detail from the canopy above Mary, with a now headless figure holding and pointing to a scroll. In medieval iconography, a blank scroll carried by an angel or a saint was a standard visual signifier of a message from God to humanity. (Foliage symbolism and scroll symbolism are explored further in the sixth article of this series).

(As with all pictures, click to see larger in a new window, click in new window to further enlarge.)

On either side of the reredos is a minstrel carving, both high on the wall, between the reredos and the adjacent column. On the left (above) is a player of a single drone bagpipe; on the right (below), a vielle (medieval fiddle) player who is singing.

Both the bagpipe and fiddle are incomplete. The bagpiper is missing the whole of his right hand and a portion of the digits of his left, together with the chanter of his pipes. Part of the fiddler’s bow is missing. One would expect to see a peg box with tuning pegs at the end of the fiddle neck, but instead we see a decorated carved head. Since there are no visible pegs and no way of getting to any hidden pegs, this instrument would be untuneable and therefore unplayable as presented. My proposed likely reason for this oddity is that, as we saw in the second article, medieval bagpipes often had chanter stocks that were carved with humorous human or animal heads, positioned so that the chanter seems to be blown by the carved head. On the bagpipe above, the whole of the chanter, including the face of the head decoration, is missing. It may be that this broken carved chanter stock head was not lost, but was kept in the Minster – iconoclasts were unlikely to have cleared up after themselves and we know other parts were kept – and then given many years later to a restorer unfamiliar with bagpipes and vielles, who affixed it not to the bagpipe, but to the vielle in place of the missing peg box.

(As with all pictures, click to see larger in a new window, click in new window to further enlarge.)

The inner roof of the reredos is exquisitely carved with heads among foliage, a Christian tradition reminding believers of the brevity of life – green quickly fades to grey – and the need to live our few short years in accordance with God’s commandments. The idea that such imagery is a hidden pagan tradition of the so-called green man is a modern invention of Lady Julia Raglan, in a culturally influential but easily-debunked article she wrote in 1939 (explored in the sixth article in this series).

On the inner roof of the reredos, among the foliage and faces, is a double horn player (two views above), with a separate mouthpiece so that both horns can be blown together. The exact identity of this horn and others already seen on the walls in the third article will be discussed below.

On the inner roof of the reredos, on the left edge of the ceiling, is the Coronation of the Virgin (above), a major theme in Christian art in the 13th to 15th centuries. Christ wears his crown as King of Heaven and gives the sign of the Trinity with his right hand. An angel crowns Mary as Queen of Heaven. Almost hidden from view, two figures behind Jesus and Mary blow long and slightly broken horns – these details shown below.

Wind instruments of various materials, with or without finger holes, have been made for a longer period of history than we can reliably ascertain. Above, for example, is the Lough Erne horn, dredged from the River Erne in north-west Ireland in 1956, dated to the 8th or 9th century. It is 58 cm long with a blowing aperture of 2.5 cm, made from a single piece of yew that was split, hollowed and then re-bound, secured with bronze rings. Horns and flutes are evident from well before the medieval period. Pictured below the Lough Erne horn are musical instruments found in 2012 in Geißenklösterle (Geissenkloesterle) Cave in Germany. Made respectively of vulture wing bone and mammoth tusk, they have been carbon dated to between 42,000 and 43,000 years old, back to the Stone Age.

Wind instruments of various materials, with or without finger holes, have been made for a longer period of history than we can reliably ascertain. Above, for example, is the Lough Erne horn, dredged from the River Erne in north-west Ireland in 1956, dated to the 8th or 9th century. It is 58 cm long with a blowing aperture of 2.5 cm, made from a single piece of yew that was split, hollowed and then re-bound, secured with bronze rings. Horns and flutes are evident from well before the medieval period. Pictured below the Lough Erne horn are musical instruments found in 2012 in Geißenklösterle (Geissenkloesterle) Cave in Germany. Made respectively of vulture wing bone and mammoth tusk, they have been carbon dated to between 42,000 and 43,000 years old, back to the Stone Age.

The oldest extant instrument, above, is from the Middle Paleolithic period (a subdivision of the Stone Age) and is of Neanderthal manufacture. Neanderthals became extinct 30,000 years ago, and this instrument is between 50,000 and 60,000 years old. It was found in 1995 at the Divje Babe I near Cerkno, Slovenia, during archaeological excavations by the Institute of Archaeology of the Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, in extensive cave dwellings on 10 levels, with 20 hearths, yielding 600 manufactured objects. Known as the Divje Babe flute, or the Neanderthal flute, it is 11.2 cm long, made from the femur (thigh bone) of a 1 to 2 year old cave bear. Using tools of bone and stone, the Neanderthal sharpened the rim for a mouthpiece and drilled 4 aligned holes – 3 on the top and 1 on the back – to create different pitches that play the diatonic scale.

The oldest extant instrument, above, is from the Middle Paleolithic period (a subdivision of the Stone Age) and is of Neanderthal manufacture. Neanderthals became extinct 30,000 years ago, and this instrument is between 50,000 and 60,000 years old. It was found in 1995 at the Divje Babe I near Cerkno, Slovenia, during archaeological excavations by the Institute of Archaeology of the Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, in extensive cave dwellings on 10 levels, with 20 hearths, yielding 600 manufactured objects. Known as the Divje Babe flute, or the Neanderthal flute, it is 11.2 cm long, made from the femur (thigh bone) of a 1 to 2 year old cave bear. Using tools of bone and stone, the Neanderthal sharpened the rim for a mouthpiece and drilled 4 aligned holes – 3 on the top and 1 on the back – to create different pitches that play the diatonic scale.

(As with all pictures, click to see larger in a new window, click in new window to further enlarge.)

These being the last of the large horns in Beverley Minster, it is time to determine their identity. Above we see them all together. The top line of horns from the north wall (bays E, F, and G) are all replacements by John Percy Baker between 1895 and 1912, based on the originals on the bottom line inside the reredos: top right and top centre are based on bottom left; and top left is based on bottom centre and right. (The photograph bottom centre is shown rotated 180 degrees so it appears the right way up to the viewer.)

It is not possible to know from the Beverley Minster stone carvings whether the protrusions on the reredos horns are functional ferrules (strengthening rings or caps covering joints) or purely decorative, and the shape gives no necessary indication of being made of metal, wood or animal horn. However, the double horn (seen again on the right) closely resembles the size and shape of an instrument called an oliphant – also olifant or olyphant – from the Old French word for elephant, made from elephant horn. In common with the much smaller hunting horn, the oliphant has no finger holes and can only play two or three notes of the harmonic series, but it was associated with royalty due to the prestige associated with its material and its typically highly-decorated presentation. This musical horn plays a role in La Chanson de Roland (The Song of Roland), a French epic poem composed between 1040 and 1115, popular until the 14th century. Roland serves in the rearguard of Charlemagne’s army and, as part of his role, he plays an oliphant. It would be fitting, then, for an oliphant to be played by an angel on the inner roof of the Beverley Minster reredos in the company of Christ and the Virgin Mary, the heavenly King and Queen.

An oliphant is on display in York Minster, seen below, held by a pair of life-size plastic hands to give the scale. It was given in c. 1030 by Ulf, a Viking nobleman, to York Minster as a token of his gift of land to the church. A more ornate oliphant is in the Victoria and Albert Museum, second picture below. This example dates from the 11th century, probably from southern Italy.

Oliphants are in evidence in medieval manuscripts, often played by angels to herald God’s Final Judgement so, just as the oliphant is sounded in battle in La Chanson de Roland, it is an instrument to sound the final battle between good and evil at the end of the world. Above and below, for example, is a series of illustrations in an English Apocalypse manuscript from the second half of the 13th century (British Library Add MS 35166, folios 12r, 13r, 13v and 15r). These illustrations suggest that some oliphants were painted or stained.

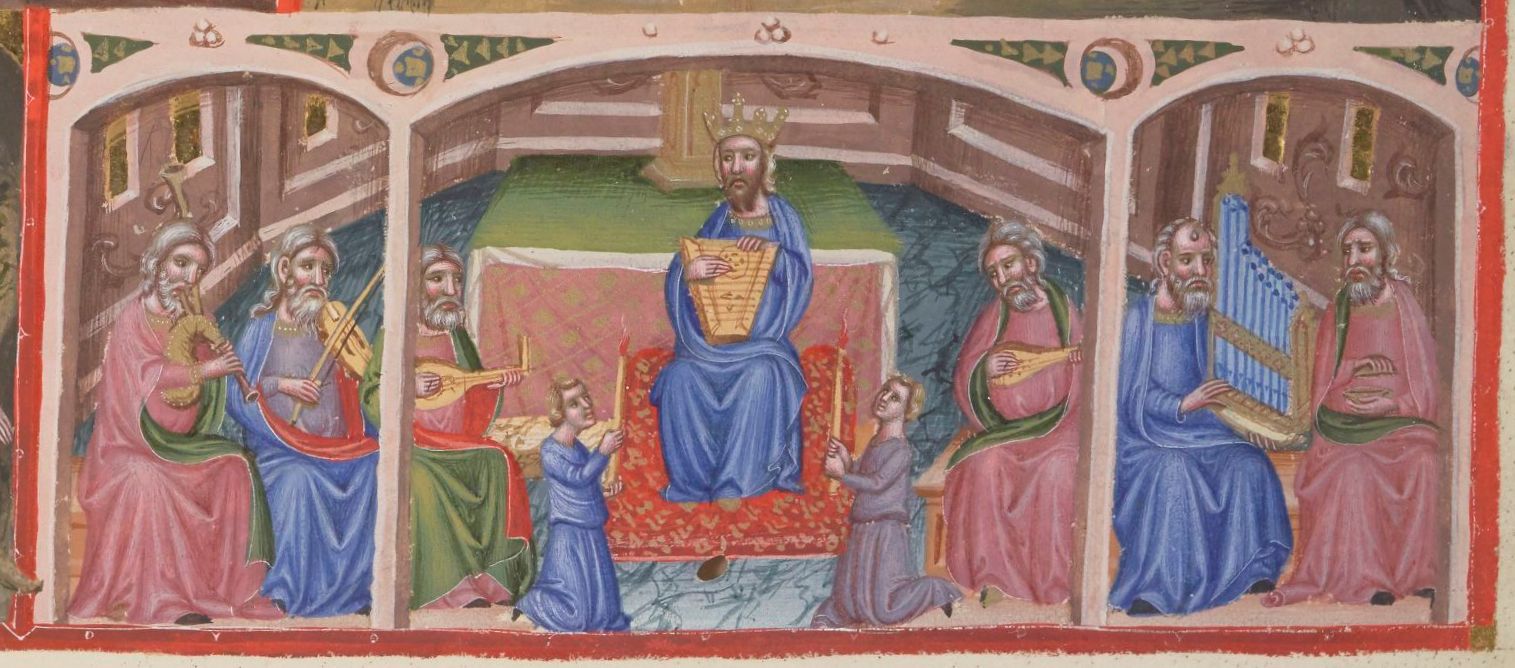

Two striking examples of an oliphant are below, both in a religious context. Left is an illustration of Psalm 131: 17, “There will I bring forth a horn to David”, on folio 75r of The Utrecht Psalter, created 820–30 in Reims or in the nearby convent of Hauvilliers, north-east France. Right is a detail from folio 3v of The Worms Bible, produced in the Middle Rhineland of Germany, c. 1175–1200 (British Library Harley 2804), from a scene that features King David playing lyre surrounded by musicians, including this player of an oliphant holding a duct flute.

That the Beverley Minster oliphant is geminate or double is worthy of note. The practice of blowing two instruments at once goes back to at least the aulos, the double reed pipe of classical Greece, seen in the image on the right from Athens, dated to 500 BCE.

That the Beverley Minster oliphant is geminate or double is worthy of note. The practice of blowing two instruments at once goes back to at least the aulos, the double reed pipe of classical Greece, seen in the image on the right from Athens, dated to 500 BCE.

Double wind instruments are a regular feature of medieval musical iconography, either playing a melody over a drone or two moving polyphonic parts. The geminate or double oliphant, lacking any finger holes and being two horns of the same size, can only play a single drone or limited parts of the harmonic series, two or three notes, a very limited range compared to other unvalved or unholed instruments such as the medieval natural trumpet or the modern bugle horn or post horn.

Below we see other examples of geminate instruments from around the time of the Beverley Minster carvings: double duct flutes from Saint Martin is knighted, a fresco by Simone Martini, Italy, 1312-18, and from folio 87v of The Luttrell Psalter (British Library Add MS 42130), England, c. 1325-40; …

… double shawms from folio 174r of The Luttrell Psalter; and double trumpets from folio 126r of The Queen Mary Psalter (British Library Royal 2 B VII), England, 1310-20.

The other two reredos instruments, behind Mary and Jesus, are much longer than oliphants, being in the shape of long, curved animal horns. An example of such an instrument is the shofar, below left, a hollow ram’s horn used in religious rituals, mentioned multiple times in The Tenakh (the Jewish holy book, known to Christians as The Old Testament) and used in Judaism for millennia. Horns from buffalos or cows may be used for musical purposes with little modification, and have been since the Stone Age.

The other two reredos instruments, behind Mary and Jesus, are much longer than oliphants, being in the shape of long, curved animal horns. An example of such an instrument is the shofar, below left, a hollow ram’s horn used in religious rituals, mentioned multiple times in The Tenakh (the Jewish holy book, known to Christians as The Old Testament) and used in Judaism for millennia. Horns from buffalos or cows may be used for musical purposes with little modification, and have been since the Stone Age.

As we see below, the protrusions at regular points on the reredos horns look too large to be the kind of decorative carvings we see on oliphants. They are more likely to be ferrules, strengthening rings to cover joints, leading to a likely identification.

As we see below, the protrusions at regular points on the reredos horns look too large to be the kind of decorative carvings we see on oliphants. They are more likely to be ferrules, strengthening rings to cover joints, leading to a likely identification.

Below we see a horn or trumpet of the same design as in the Minster’s reredos. This is a narsingha or ransingha, which literally means buffalo horn (shinga or srnga in Sanskrit), denoting the material from which it was originally made. Narsinghas are made from metal, in imitation of the animal horn shape, and the example below is made of copper with ferrules of brass. As we see below right, the sections can be deconstructed for ease of carrying. In Nepal and India, the narsingha or ransingha trumpet was used in battle, like the oliphant, and in religious ceremonies, for which it is still used today to rid the location of evil spirits and make way for the holy occasion.

The Beverley instruments, though essentially the same as narsinghas, would of course not have been known by that name in England. Trumpets of both horn and metal are common in western medieval iconography, usually straight, sometimes folded (the tubing in a neat ellipse), and occasionally curved in a similar way to those in the Beverley reredos. We see two such examples below, both from The Hours of Charles the Noble, King of Navarre, c. 1404 (Cleveland Museum of Art, 64.40), folio 272r on the left and folio 316r right.

Saint Katherine’s chapel

(As with all pictures, click to see larger in a new window, click in new window to further enlarge.)

In Saint Katherine’s chapel, to the south of the reredos, is a hidden gem. Above we see the highly decorated screen that partitions the chapel from the altar, with the south side of the Percy tomb visible through the screen. A closer look teaches the lesson that the scrawling of graffiti is not a modern phenomenon since, as we see, in 1526 congregants or visitors scratched on their initials, messages and dates, showing that a lack of respect and appreciation for art and heritage is no new thing: 351 years later, in 1877, they were still doing the same.

Saint Katherine’s chapel is located in the area of the church built in 1220-60. The date of the screen would appear to be contemporaneous, judging by what we find at the foot of the screen, ordinarily out of view: crude but charming wooden portraits of a three string fiddler, a man praying, a player of nakers, a single drone bagpiper, and two rather fed-up looking women.

The south transept

(As with all pictures, click to see larger in a new window, click in new window to further enlarge.)

In the south transept, built 1220-60, is a pillar with a carving of three musicians, seen in context above. On the Beverley Minster floor plan that begins and ends this article, this pillar is distinguished by being ringed. Below we see the three musicians more closely, remaining in the state they were reduced to after being vandalised by Puritans.

The musician on the left is a playing a vielle (medieval fiddle), now in a poor state, half destroyed by iconoclasts, but there is still enough remaining to clearly identify the decorated string holder, five strings, two sound holes and the remains of a bow, as we see in the detail below, turned 90 degrees.

On the central figure (shown again on the right), the left arm, right hand, right leg, face and instrument are now completely lost. The missing left arm means that any suggestion of a playing position is absent, and there is no remaining indication of what the instrument may have been.

On the central figure (shown again on the right), the left arm, right hand, right leg, face and instrument are now completely lost. The missing left arm means that any suggestion of a playing position is absent, and there is no remaining indication of what the instrument may have been.

The player on the right of the three (seen in more detail in the two photographs below) has an instrument that is now almost completely destroyed, but still discernable. The one remaining sound-hole, the size of the largely missing instrument and the position of the now-missing hands, obvious from the arms, indicates a harp, with the ridged lines below it being the remains of a harp bag, covering a putative support for the instrument, an arrangement we have already seen with the harp on the inner roof of the Percy tomb. (Harp bags are discussed in the in the second article.)

What does this mix of instruments tell us about 14th century minstrelsy?

In Beverley Minster there are the following numbers of original carved instruments from c. 1330-90, from the most to the least numerous, with John Percy Baker’s late 19th or early 20th century additions in brackets (+ Baker’s number):

10 medieval fiddles, vielles or viellas

9 bagpipes

8 harps

7 portative organs

3 shawms, including 2 bombards

3 timbrels (+ 2)

3 psalteries

3 gitterns (+ 2)

3 citoles

3 pipe and tabors

3 pairs of nakers

3 horns, comprising 1 double oliphant and 2 long metal horns

3 lost wind instruments

3 lost instruments

2 trumpets

1 symphonie (+ 1)

1 drum

1 pair of cup cymbals

1 probable singer (+ 2)

1 hunting horn (+ 1)

This makes a remarkable total of 71 representations in stone and wood of 14th century musicians in a single church.

While I am certain of the identification of 69 of these as original, I have doubts over two. The stone of the timbrel player on column 2 of the arcade and of the timbrel player on the capital of column 2 seems rather fresh for 14th century, but other stonework in the arcades which is certainly original is also remarkably well preserved, and the style of the carving is in keeping with the originals. Both are far too high to examine up close. Even if we were to decide these 2 were wholly the work of John Baker, that still leaves an extraordinary 69 images of medieval minstrels, and it is certainly possible that some of the figures that were completely destroyed were musicians, taking the number higher than 71.

It is not possible to know if these numerical proportions are representative or typical of the mix of instruments played in 14th century Beverley or England generally, but there are reasons to think they may be. There are more fiddles (vielles) than any other instrument, almost as many bagpipes as fiddles, almost as many harps as bagpipes, and almost as many portative organs as harps. We will briefly examine the importance of these four most numerous instruments.

(As with all pictures, click to see larger in a new window, click in the new window to further enlarge.)

If the testimony of Johannes de Grocheio is taken as the common view, as he claimed it was, it would not be surprising for vielles to outnumber other instruments. In his Ars musice, written in Paris between the 1270s and 1300, he stated that “instruments with strings have primacy. Of this type are the psaltery, the harp, the lyre, the gittern and the vielle. For in these the discernment of sound is more subtle and better … amongst all stringed instruments, the vielle is seen to prevail. For just as the intellectual soul contains other natural forms virtually in itself as the square the triangle and the greater number the lesser, so the vielle contains other instruments virtually in itself.” Precisely what Johannes meant by this is open to interpretation. He cannot have meant that the sounds produced by other instruments can also be produced by the vielle, as it stands to reason that a fiddle cannot produce the tone of a piped organ, blown shawm or plucked citole. What he appears to have meant is that a vielle is capable of great dynamic range, from soft to loud, and a variety of timbres, from gentle to coarse, making it ideal for all types of music, whereas other instruments have a lesser scope. This interpretation seems to be confirmed by his next statement: “Although some instruments move the spirits of men more by their sound, such as the drum and trumpet in feasts, spear games and tournaments, in the vielle, however, all musical forms are subtly discerned.”

There are almost as many bagpipes as vielles in Beverley Minster, and it is not coincidental that the fiddle’s reputation as the universal instrument, encompassing all others, was a status also given the bagpipe. In the medieval period, the bagpipe was called musa, i.e. it had the name of the muses who inspired music, and the name of music itself. German monk, historian, and music theorist, Regino of Prüm, c. 842–915, in his Epistola de harmonica institutione, refers to the fact that the bagpipe was known in the Roman Empire: “Music is named after the muse, which is an instrument preferred by the ancients above all other musical instruments, because by its nature it contains all the perfections.” Similarly, 12th century music theorist John of Cotto or Cotton (Johannes Affligemensis or John of Affligem) wrote in his De Musica cum Tonario, c. 1100, “It is called music, as some would have it, from musa [bagpipe], which is a certain musical instrument proper and pleasant enough in sound. But let us consider by what reasoning and what authority music derives its name from musa. Musa, as we have said, is a certain instrument far surpassing all other musical instruments, inasmuch as it contains in itself the powers and methods of them all. For it is blown into by human breath like a pipe, it is regulated by the hand like the fiddle, and it is animated by bellows like organs. Hence musa derives from the Greek mese, that is, central, for just as diverse paths converge at some central point, so too do manifold instruments meet together in the musa. Therefore, the name music was not unfittingly taken from its main exponent.”

There are almost as many harps as bagpipes in Beverley Minster. While both the vielle and the bagpipe were thought of as encompassing all other instruments, the harp was a hugely popular instrument as it symbolically represented the story of divine salvation.

The idea of the harp was conceived in three ways. First, it was the instrument of King David, author of the Psalms, the songs of praise in the Old Testament. Second, the shape of the harp and its materials – a wooden frame with gut strings – represented Christ’s crucifixion, his sacrifice to bring salvation. Third, the harp was often depicted being tuned, to symbolise the creation of harmony between God and humanity through Christ. Below we see two images of King David tuning a harp, combining these meanings: the harp as King David’s instrument, symbol of the cross, and it being tuned a symbol of divine harmony. Left, a clerical vestment dated c. 1315, now in the Musee des Tissus (Textile Museum) in Lyon, France. Right, folio 8r of The Rutland Psalter, England, c. 1260 (British Library Add MS 62925).

There are almost as many portative organs as harps in the Minster. While the portative organ is shown in medieval iconography in a variety of contexts – including some portative organists dancing while playing – the organ had a special relationship with sacred music, being the only instrument allowed by the church to accompany the singing of the liturgy, the most holy and formal part of worship. Portative organ and medieval keyboard specialist Cristina Alís Raurich reports that she has found evidence for the organ being played in all contexts except by troubadours, the lyric poets of Occitania (now southern France), though there is some potential evidence of it being played by trouvères, the troubadours’ northern French counterparts.

The whole manuscript can be viewed here.

Above and below, two images from a late 13th century trouvère chansonnier, MS Reg. lat. 1490, in the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Rome. The image above, from folio 94r, may indicate that the portative organ was a trouvère instrument. If so, then folio 100r below indicates that trouvère songs were also accompanied by bagpipes. The lack of explanation and the rarity of such images makes it impossible to ascertain whether such iconography should be taken literally, figuratively, or decoratively.

Beverley Minster’s minstrels were carved between c. 1330 and 1390, representing English music-making in the 14th century. Whether it is correct that more fiddles, bagpipes, harps and portative organs were played than other instruments, and in that order of prominence, as represented in the Minster’s iconography, is impossible to say. But we can state, as above, the cultural and philosophical significance of these instruments according to medieval witnesses.

The list of instruments in Beverley Minster is significant not only for what is represented, but for what is absent.

All of the bowed instruments are played da braccio, on the arm: there are no bowed instruments in the Minster played da gamba, on the leg. Since the latter way of playing is present in some medieval iconography, there may originally have been one or more da gamba instruments among those that were destroyed, but this cannot be proven. What we see in the Minster represents the prevalent way of bowed playing at the time, before the popular rise of the renaissance viol(a) da gamba.

Similarly, there are no rebecs in the Minster. While some modern players of medieval music use the rebec for medieval music of all dates, there is no firm evidence for it before c. 1400, around 10 years after the last musician was carved in the Minster.

There were lutes between c. 1330 and 1390, but none are represented in the Minster. The lack of lutes in the Minster is testament to a change that was yet to take place. In the 14th century, the European lute was still in transition from being the imported Arabian oud, it was still fretless, and it had not yet come into its own and achieved the high status it would gain in the 16th century. It was not until the early 15th century that images of lutes appeared in any number, having now gained frets, and it would not be until the second half of the 15th century that the lute would begin to supersede the gittern (of which the Minster has 3) in importance.

None of the harps in the Minster have brays. Brays are L shaped wooden pegs to hold the string in place, turned for the string to vibrate against, making it louder, with a frisson of sound distortion. This, too, was essentially a future change. The first evidence for the bray harp is from 1370, within the period of the Minster’s construction, but brays on harps were not ubiquitous until c. 1400, 10 years after the Minster’s minstrel masons finished carving. From c. 1400, the bray harp became the standard harp for more than two centuries, and for much longer in Germany.

As we should expect, there are no guitars, as evidence for a guitar of any kind does not appear until the last quarter of the 15th century, contemporaneously in Spain and Germany.

Perhaps surprisingly, there are no recorders in the Minster. The recorder is a complex type of flute with an internal duct, a fixed windway formed by a wooden plug or block, distinguished visually from other internal duct flutes by having seven finger holes on top and a single hole at the back for the thumb of the upper hand. The first instruments of this type appeared in iconography in the second decade of the 14th century; and the first use of the name, “Recordour”, refers to the playing of the Earl of Derby in 1388, before he became King Henry IV; both events exactly in the period of the Minster’s carved minstrels. Before then, the more simple type of blown pipe was a flageolet or flute. There are few surviving medieval instruments, but excavations have discovered eight medieval recorders or transitional modified duct flutes or flageolets on the way to becoming recorders – seven from the 14th century and one from the 15th. This makes the absence of recorders or flageolets in the Minster’s iconography more surprising, but they may possibly have been among the lost instruments smashed completely during the period of iconoclasm (described in the first article).

That completes the tour of 14th century musicians in the Minster. The fifth article discusses why they appear in Beverley in such abundance, using clues about documented medieval performance practice nationally, in the north east of England, and in Beverley specifically. The sixth article explores the 14th century allegorical stone carvings; and the seventh article the 16th century musical misericords and early 20th century Gothic Revival carvings of musicians on the organ screen. The final article surveys the 19th, 20th and 21st century literature about Beverley Minster and its medieval minstrels, and asks why they have been so poorly served to date.

Thank you

Grateful thanks to David Jarratt-Knock for identifying the oliphants.

Beverley Minster floor plan and instrument inventory

The floor plan above shows the various stages of building of Beverley Minster. Modern sources do not always agree on precise construction dates, so I have used the widest suggested timescales. The arcade columns are numbered 1 to 18 for convenience, and descriptions of minstrels in the arcades follow this scheme in the second article. The letters A to R on the inside of the west, north and south walls indicate bays, and this lettering system is used to indicate the location of minstrels in the third article.

The 14th century minstrels are listed below by location in a table cataloguing instruments by type, from the most to the least numerous.

© Ian Pittaway. Not to be reproduced in any form without permission. All rights reserved.

Bibliography

The eighth and final article is a survey of and commentary on the literature to date about the medieval minstrels of Beverley Minster.

Barnwell, P. S. & Pacy, Arnold (ed.) (2008) Who built Beverley Minster? Reading: Spire Books.

BBC Reel (2022) The 60,000-year-old artefact rewriting Neanderthal history. Available online by clicking here.

Bowles, Edmund A. (1957) Were Musical Instruments Used in the Liturgical Service during the Middle Ages? The Galpin Society Journal, Vol. 10 (May 1957), pp. 40-56. Available online by clicking here.

Bowles, Edmund A. (1959), Once More ‘Musical Instruments in the Liturgical Service in the Middle Ages’. The Galpin Society Journal, Vol. 12 (May 1959), pp. 89–92. Available online by clicking here.

Cerkno Tourist Board (2018) The Neanderthal Flute. Available online by clicking here.

Duffin, Dr. Ross W. (2021) Recorder (Baroque). Available online by clicking here.

Ghosh, Pallab (2009) ‘Oldest musical instrument’ found. Available online by clicking here.

Gilbert, Adam K. (2000) Bagpipe. In: Duffin, Ross W. (ed.) A Performer’s Guide to Medieval Music. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Grocheio, Johannes de (1270s–1300, modern publication 2011) Ars musice. Edited and translated by Constant J. Mews, John N. Crossley, Catherine Jeffreys, Leigh McKinnon, and Carol J. Williams. Kalamazoo: Medieval Institute Publications.

Hayman, Richard (2010) The Green Man. London: Shire Publications. Available from Bloomsbury by clicking here.

Horrox, Rosemary (ed.) (2000) Beverley Minster: an illustrated history. Beverley: The Friends of Beverley Minster.

Lander, Nicholas S. (1996) A memento: the medieval recorder. Surviving specimens. Available online by clicking here.

Lander, Nicholas S. (1996) Recorder History: Medieval period. Available online by clicking here.

Mannyng, Robert (written 1303, this edition 1862) Roberd of Brunnè’s Handlyng Synne (written A. D. 1303) with the French treatise on which it is founded, Le Manuel des Pechiez by William of Waddington, now first printed from MSS. in the British Museum and Bodleian libraries. Edited by Frederick J. Furnivall. London: J. B. Nichols and Sons. Available online by clicking here.

Murthy, Y. K. (2013) Antique Copper And Brass Indian Ethnic Narsingha Trumpet. Available online by clicking here.

Natural History Museum of Slovenia (undated) Neanderthal Flute – the Flute from Divje Babe. Available online by clicking here.

Page, Christopher (1979) Jerome of Moravia on the Rubeba and Viella. The Galpin Society Journal, Vol. 32 (May 1979), pp. 77-98. Available online by clicking here.

Page, Christopher (1987) Voices & Instruments of the Middle Ages. Instrumental practice and songs in France 1100-1330. London: J. M. Dent & Sons.

Pittaway, Ian (2018) The medieval portative organ: an interview with Cristina Alís Raurich. Available online by clicking here.

Pittaway, Ian (2021) “the verray develes officeres”: minstrels and the medieval church. Available online by clicking here.

Rastall, Richard (1968) Secular Musicians in Late Medieval England. A thesis presented to the Victoria University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by George Richard Rastall. Available online by clicking here.

Rois, Robert (2013) The Oliphant and Roland’s Sacrificial Death. Anthropoetics: the Journal of Generative Anthrolopology, Vol. 18, no. 2, Spring 2013. Available online by clicking here.