In the middle ages, minstrels were regularly accused by church commentators of vanity, idleness, inflaming carnal desire, lechery, and leading others into vice. In the 12th century, Bishop of Chartres John of Salisbury expressed the view that all minstrels should be exterminated. Because of this reputation, the church wanted to ensure that its most sacred music was different in kind to minstrel music, and restated several times that only the voice and organ were allowed in the liturgy, not instruments of minstrelsy. Still some writers complained bitterly of secular styles of music corrupting singers’ voices in sacred chant.

In the middle ages, minstrels were regularly accused by church commentators of vanity, idleness, inflaming carnal desire, lechery, and leading others into vice. In the 12th century, Bishop of Chartres John of Salisbury expressed the view that all minstrels should be exterminated. Because of this reputation, the church wanted to ensure that its most sacred music was different in kind to minstrel music, and restated several times that only the voice and organ were allowed in the liturgy, not instruments of minstrelsy. Still some writers complained bitterly of secular styles of music corrupting singers’ voices in sacred chant.

How can we account for the contradiction between clergy’s invectives against minstrels and the innumerable quantity of medieval and renaissance paintings in which gitterns, shawms, harps, fiddles, lutes – the instruments of minstrels – are shown in worship of the Virgin Mary and in praise of the infant Jesus? How can we reconcile the critiques of clerics against minstrels with their regular appearance in religious manuscripts, their likenesses carved in churches, and their employment by the church? This article seeks answers through the evidence of medieval Christian moralists; church councils; music treatises; religious paintings; records of church ceremonies; and the relationship of the church with organised minstrelsy.

Top row, left to right: church singers (f. 171v); bishop (f. 31r); pilgrim (f. 32r); nun (f. 51v).

This row, left to right, players of: harp (f. 174v); pipe and tabor (f. 164v);

organistrum, also called the symphonie (f. 176r); portative organ (f. 176r).

Church criticism of minstrels

A previous article, Jheronimus Bosch and the music of hell. Part 2/3: The Garden of Earthly Delights, explored the savage and everlasting punishments in hell that Bosch wished on musicians in his triptych of 1495–1505 (detail above). They include a lutenist tied to the neck of a giant lute with fret-gut, watched by onlookers and taunted by hell’s serpents; a harpist crucified on his harp, the strings piercing his neck, spine and anus; a wind player forced to carry a giant bombard (shawm) on his back with a recorder inserted in his rectum; a percussionist trapped inside a drum with a demon banging the skin; a trumpeter playing so loudly it pains the ears of those around him; and sinners in a mock dance, forced to process with partners from hell around a giant phallic pink bagpipe that plays only one note. Bosch made the same blistering attack on music and musicians in all his other works, as shown in Part 3/3: Music and musicians in the complete works of Bosch.

A previous article, Jheronimus Bosch and the music of hell. Part 2/3: The Garden of Earthly Delights, explored the savage and everlasting punishments in hell that Bosch wished on musicians in his triptych of 1495–1505 (detail above). They include a lutenist tied to the neck of a giant lute with fret-gut, watched by onlookers and taunted by hell’s serpents; a harpist crucified on his harp, the strings piercing his neck, spine and anus; a wind player forced to carry a giant bombard (shawm) on his back with a recorder inserted in his rectum; a percussionist trapped inside a drum with a demon banging the skin; a trumpeter playing so loudly it pains the ears of those around him; and sinners in a mock dance, forced to process with partners from hell around a giant phallic pink bagpipe that plays only one note. Bosch made the same blistering attack on music and musicians in all his other works, as shown in Part 3/3: Music and musicians in the complete works of Bosch.

Bosch was not alone. In the medieval and renaissance periods, there was a regularly expressed ecclesiastical hatred of secular musicians, who were associated with lust and lechery, with being idle and indecent, and with leading others astray. The criticism was levelled at those who enjoyed hearing secular music, at those who danced to it, at those who played it as a pastime, and especially at professional musicians. The latter were variously called minstrels, mimi, jongleurs, jugleurs, joculators, histriones and, only in England, gleemen. These words were used indiscriminately and interchangeably to mean any paid entertainer – instrumentalists, singers, composers, poets, story-tellers, acrobats, jugglers, dancers, fools, mimes, conjurors, and those with trained performing animals. These skills were not separate and discreet: a minstrel/jongleur/gleeman was often an all-round entertainer, proficient on a large range of musical instruments, as well as having other skills, such as being a singer, story-teller, mimic and/or acrobat.

There were some edicts specifically aimed at excluding minstrels/jongleurs. For example, Charlemagne or Charles the Great, King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, Emperor of the Romans from 800, enforced his rule with legislative acts called capitularies. In his capitulary of 789, Admonitio generalis, he presented himself as the saviour of his subjects’ morality and reformer of church discipline. Clergy were charged with establishing schools in which Psalms would be sung and the faith spread. The church would use the Roman liturgy and memorise Roman chants. Clergy would lead by moral example and, to enforce their moral worthiness, bishops, abbots and abbesses were forbidden from admitting jongleurs on church grounds. Similarly, under the rule of Philip VI of France, the Synod of Chartres in 1358 forbade anyone under holy orders from employing jongleurs.

One criticism of minstrels was that their humour spoke the truth that it was politic not to say. In c. 960, the English King Edgar complained that the common people and the military whisper the shortcomings of monks privately, while “the mimi sing and dance them in the market-places”.

Some criticised minstrels in a way that appears to blame them for being working class. For example, 13th century Franciscan, Juan Gil de Zamora (or Gilles de Zamore), royal secretary of Iberian King Alfonso X of Castile (the monarch who was chief author of the Cantigas de Santa Maria), wrote in his Ars Musica, “And of this instrument [the organ] alone the church has made use in various kinds of singing, in prose sequence, and in hymns, other instruments being commonly rejected because of the abuses of the jongleurs.” One of their “abuses”, from Juan Gil’s viewpoint, was empty praise for any temporary employer who paid for it. Majorcan Franciscan, Ramon Llull (c. 1232–1315/16), criticised a jongleur at length who praised a knight for a small fee; and English author and Bishop of Chartres, John of Salisbury (c. 1120–1180), associated secular musicians in general with “empty praises like unto wind instruments”: songwriters and musicians “seldom or never are caught praising a man for that which is truly his own.” In other words, minstrels were accused of being fundamentally dishonest for money, and of promoting the sin of pride.

Such critics, in their privileged position as aristocrats and clerics in the medieval social hierarchy, showed no understanding of or sympathy for the financial insecurity of minstrels. Those minstrels lucky enough to be liveried, in a uniform to display their employer’s identity, were high status, paid by the local municipality or attached to a monarch, a noble or a prelate (bishop or abbot), but even such high status work was not usually a full-time occupation, since it was generally seasonal, or required only for specific occasions. The rest of the time they were looking for the next gig, like any other jobbing musician. It was a given in the strictly hierarchical medieval and renaissance society that being hired or gaining a patron required obsequious praise, as we see from any foreword in any surviving book by an author with a patron. What Juan Gil, Ramon Llull, John of Salisbury and others criticised in the minstrels/jongleurs was simply a cultural norm and a mechanism of financial survival they were too privileged to have to consider.

Others criticised minstrels for indecency. In his work of c. 1159, Policraticus, sive de nugis curialium et de vestigiis philosophorum (Policraticus: Of the frivolities of courtiers and the footprints of philosophers), Bishop of Chartres John of Salisbury forcefully expressed his view of “actors and mimes, buffoons and harlots, panders [pimps] and other like human monsters, which the prince ought rather to exterminate entirely than to foster … the law … not only excludes such abominations from the court of the prince, but totally banishes them from among the people of God.” John lumps together performing minstrels with pimps and prostitutes. For him, and for all who thought like him, there was no moral distinction between them, as they all promoted the pleasures of the senses, the sin of lust.

There are records of real excesses by professional performers which would shock an audience of any era. For example, one 11th century ludus histrionum – play performed by actors – included a tame bear and an actor exposing his penis, smeared with honey. You can imagine the rest. In his Policraticus, John of Salisbury complained that “even those whose exposures are so indecent that they make a cynic blush are not barred from distinguished houses … they are not even turned out when, with more hellish tumult, they defile the air and more shamelessly disclose that which in shame they had concealed”, i.e. they speak obscenities and show their private parts: “Does he appear to be a man of wisdom who has eye or ear for such as these?” Having criticised minstrels for their immoral crudeness, John’s fantasy about them is hardly better. When not wishing them banished or dead, he wanted them humiliated: “Who would, however, not be glad to see and laugh when a juggler is drenched with urine, his tricks disclosed, and when eyes that have been blinded with his magic find their power restored?”

The same idea about the wantonness of musicians and those they consort with is expressed by Geoffrey Chaucer (below, as he appears in Thomas Hoccleve, The Regement of Princes, 1430-40) in The Pardoner’s Tale of The Canterbury Tales, written 1387–1400. The Pardoner’s Tale is set in Flanders, where the sinful follies of the young are listed as rioting, gambling, visiting brothels and taverns, playing harps, lutes and gitterns, dancing and playing dice at all hours, and excessive eating and drinking. They are soon joined by others hawking their sinful wares:

And right anon than comen tombesteres

And right anon than comen tombesteres

Fetys and smale, and yonge fruytesteres,

Singers with harps, baudes, wafereres,

Whiche been the verray develes officeres

To kindle and blowe the fyr of lecherye,

That is annexed un-to glotonye

And very soon there come the dancing girls,

Shapely and slender, and young girls selling fruit,

Singers with harps, prostitutes, cake sellers,

Who are the very devil’s servants

To kindle and blow the fire of lechery

That is joined to gluttony

Flemish Dominican friar Thomas van Cantimpré told a story expressing his belief that the sins of lusty musicians would not go unpunished by God in this mortal life. His Bonum universale de apibus (General good of bees), written c. 1260, is a spiritual allegory likening the religious life to a colony of bees, reproduced many times and internationally in manuscripts and prints into the 17th century. Thomas included the following exemplar: “By his cavorting and other misbehaviour, the bagpiper led young men and maids into lasciviousness and the singing of indecent songs. Two shepherds witnessed how a bolt of lightning struck the piper, killing him and smiting off an arm.” Jheronimus Bosch clearly knew, enjoyed, and approved of the message in its Dutch translation as Het Biënboec, 1488, as this one-armed divinely punished bagpiper is depicted in his Temptation of Saint Anthony triptych (as we see in this article).

Other Christian writers imagined the consequences in the next life. In his Van de viere utertse (Of the four utterances), Dennis the Carthusian (1402/3–1471) of The Netherlands wrote: “Those who now take delight in songs, in idle and indecent words, in chattering and frivolity, will they not be punished through their sense of hearing?” We see on the right how, in the hell panel of The Garden of Earthly Delights, Jheronimus Bosch depicted this visually next to a bagpipe.

Other Christian writers imagined the consequences in the next life. In his Van de viere utertse (Of the four utterances), Dennis the Carthusian (1402/3–1471) of The Netherlands wrote: “Those who now take delight in songs, in idle and indecent words, in chattering and frivolity, will they not be punished through their sense of hearing?” We see on the right how, in the hell panel of The Garden of Earthly Delights, Jheronimus Bosch depicted this visually next to a bagpipe.

Similarly, the author of the anonymous MS 19549 in the Royal Library of Belgium, c. 1470, liked to imagine music-lovers suffering in hell because music was viewed as a gateway sin, leading to further transgressions: “The devils stood beside him, blowing trumpets; and flames shone out of his nostrils, ears and eyes. And they said: ‘This is what you have to suffer because in the world you listened to idle songs and tunes.’ And they made snakes twine about his neck and arms, saying, ‘This is for embracing women unchastely.’”

The Dutch Dat sterfboeck (The book of death), 1488, imagines further punishments in hell for musical revellers: “Their dancing and singing and all their idle games are turned to fighting and grievous lamentation. Their pipers now are fierce devils blowing the trumpets of hell.”

A popular 14th century work by the French Cistercian, Guillaume de Deguileville, translated into English in 1413 as The Pylgremage of the Sowle, has a passage in the voice of the minstrel, again expressing the idea of the gateway sin: “No minstrel is better received than I, for I am the one that gives most joy. But they are great fools, for I deceive them all. I am the siren from the sea and often cause those who listen to my sweet songs to drown. My true name is Flattery, the niece of Treachery, the eldest daughter of Falsehood, and foster mother of all evil.”

Music in the liturgy

We would expect, then, “because of the abuses of the jongleurs”, as Juan Gil de Zamora put it, that the medieval church would give minstrels and their musical instruments a wide berth, not allowing their sinful influence to sully the sanctity of worship. Dr. Edmund A. Bowles’ survey, Were Musical Instruments used in the Liturgical Service during the Middle Ages?, studied a huge array of historical documents, concluding that there is no evidence of any musical instrument other than the organ ever being used or allowed for use in the liturgy in a western Catholic Church, that the pronouncements of church leaders specifically forbade it, and that this proscription is confirmed by evidence of practice. Dr. Bowles’ impressive survey cites, among his examples, the treatises of Guido d’Arezzo (Micrologus, Italy, c. 1026) and Philippe de Mézières (Nova religio passionis, France, 1367–1368), church rulings banning all instruments in the liturgy except the organ, such as the Church Councils of Trier (1221), Lyons (1274), Milan (1287) and Vienna (1331), and several eye-witness accounts of the liturgy in which only the organ is mentioned.

The Luttrell Psalter (BL Add MS 42130, f55r), 1325–1340 (right). The size and design of the

instrument makes it necessary for one person to work the bellows while the other plays.

Not only did the Catholic Church rule that music in the liturgy should be made only with voices and the organ, they restated this ruling many times over a long period. That they did so may indicate breaches of the prohibition. The Council of Milan (1287), for example, specifically names the recorder and clarion (trumpet) as banned instruments, and it’s difficult to conceive why this should be so if they weren’t being played. Still, it remained the case that voices and organ only was the official and reinforced view, so any breaches, if they did occur, continued to be censured.

Alarmingly, for those like English Cardinal Robert of Courçon or Robert Curzon, the secular musical style of minstrelsy influenced the singing of sacred music. He complained in his Summa, c. 1208, about a new method of organum or musical accompaniment, raging against “masters of organum who set minstrelish and effeminate things before young and ignorant persons, in order to weaken their minds … If, however, some sing any organa on a feast-day according to the liturgical customs of the region, they may be tolerated if they avoid minstrelish little notes.” Robert’s account tells us that minstrels played fast running passages, “minstrelish little notes”, copied vocally in the new style of church organum, which he considered unfit for church music because it was frivolous and hubristic, attracting attention to the singer/musician instead of God. As John of Salisbury put it in his Policraticus, c. 1159, anyone who “expresses passion or vanity [in music], who prostitutes the voice to his own desires, who makes music the medium of pandering [pimping, i.e. stimulating the carnal senses], is indeed ignorant of the song of the Lord and is revelling with Babylonian strains in a foreign land … our own age, descending to romances and similar folly, prostitutes not only the ear and heart to vanity, but also delights its idleness with the pleasures of eye and ear. It inflames its own wantonness, seeking everywhere incentives to vice.” In other words, the emotions stirred by secular music are corrupting, leading to other sinful passions, so these secular styles have no place in sacred music.

Robert Curzon did not have his way. The “masters of organum who set minstrelish and effeminate things before young and ignorant persons” were internationally popular, influential, and their music has survived in church manuscripts. You can hear an example of the “minstrelish little notes” Robert Curzon complained about by clicking on the picture below. This is the organum quadruplum, Sederunt principes by Pérotin (fl. c. 1200), composer of the Notre Dame school of polyphony, contemporaneous with Curzon.

Music treatises

While there are many references in religious writings to the immorality of minstrels as a whole class of people, several medieval music treatises survive, all written by authoritative ecclesiastics, which describe musical instruments and/or secular musical forms, and not one of them suggests those forms or instruments are, ever have been, or ever should be prohibited. A few examples will suffice.

The anonymous Summa Musice, c. 1200, a manual for young learners of Gregorian chant, uses musical instruments to teach about intervals and describes three classes of instruments – stringed, those with apertures, and those made from vessels which “are formed in the manner of hollow pots”. Summa Musice gives Latin names for wind instruments that are difficult to decode precisely (organa, tibie, cornua, muse, syringe, flaiota, fistule, tube); names the stringed instruments cithare (harp), psaltery, vielle, symphonia or organistrum, monochord, phiale and chori (these last two unidentified); identifies the string materials metal, silk and gut; names the percussion instruments cymbala (cup cymbals), pelves, campane, olle (the latter three unidentified); and states that “stringed instruments … are tuned in the consonances of octave, fourth and fifth, and by putting down their fingers the players of these make tones and semitones for themselves”. The author positively encourages his young pupils to play a musical instrument as an aid to singing chant: “He should learn the chant by heart so that he may sing in a more accomplished fashion when he is alone … and if he has perhaps forfeited a teacher’s offer of help and favour, then he should take extra care and also play musical instruments, especially those like the monochordium and the symphonia which is called organistrum. He should also study to play the organ. On instruments of this kind the note cannot readily go astray, nor be twisted from its proper pitch, because the notes can easily be studied with the aid of fixed and labelled keys and then promptly performed by the singer without an associate teacher.”

Left: BnF Français 1038, f.14v. Right: Pórtico de San Juan, Catedral de León, Spain.

The purpose of Johannes de Grocheio’s Ars musice, written in Paris between the 1270s and 1300, is to fulfil a request: “Since certain young men, my friends, have affectionately asked me to explain to them something in brief about musical teaching, I wanted to accede to their requests presently”. He was born Jean de Grouchy, Latinised to Johannes de Grocheio; he probably grew up in Normandy in an aristocratic family; he studied music and philosophy in Paris; is credited in one copy of Ars musice (the Darmstadt manuscript) as “magister” and “regens Parisius”, master and resident teacher in Paris; and circumstantial evidence in Ars musice suggests he may have taught music at the Basilica of Saint-Denis (now known as the Basilique-cathédrale de Saint-Denis). Since he writes so warmly of musica vulgalis, secular music, these biographical details are critical for our present subject.

Ars musice describes types of musical instruments, making specific mention of trumpets, reed-pipes, pipes, organs, drums, cymbals, and bells, noting that “instruments with strings have primacy. Of this type are the psaltery, the cithara [a general term for a stringed instrument, probably the harp in this context], the lyre, the gittern and the vielle.” He especially praises the vielle, the medieval fiddle: “amongst all stringed instruments seen by us, the vielle is seen to prevail. For just as the intellectual soul contains other natural forms virtually in itself as the square the triangle and the greater number the lesser, so the vielle contains other instruments virtually in itself … The good artist generally introduces every cantus [ecclesiastical chant] and cantilena [vocal music with a prominent top line] and every musical form on the vielle.”

Johannes de Grocheio gives some explanation of secular musical forms, the stantipes (estampie), ductia, nota, and carol. He describes sung estampies as follows: “A cantilena which is called stantipes is that in which there is diversity between the parts and the refrain” such that it “makes the spirits of young men and girls focus on it because of its difficulty and diverts them from depraved thought.” He suggests, then, that the stantipes, sung and played by secular minstrels, is morally and spiritually beneficial. He describes the ductia as “an unlettered sound … because it lacks letter and text”, i.e. an instrumental rather than a vocal form, “And they arouse the spirit of man to move decorously according to the art which they call dancing”. He states that a ductia usually has three puncta (literally punctuations, meaning sections), but some have four, and “There are some called notae, however, with four puncta that can be rendered as a ductia.” There are also vocal ductias: “a ductia is a cantilena light and swift in both ascent and descent, which is sung in carols [sung dances] by young men and girls … for this draws the hearts of girls and young men and takes them away from vanity and is said to be effective against the passion which is called love sickness.” Again, for Johannes de Grocheio, the secular ductia and carol, performed by minstrels, are positive influences, and dance is a force for good.

Two part instrumental, probably a ductia,

British Library Harley 978, folio 8v-9r, c. 1261–65,

played by Ian Pittaway on citole and gittern.

Most notably, de Grocheio uses the common didactic method of explaining his subject in relation to what is already familiar to his audience, and he does so by comparing sacred chant with secular musical forms: “The responsory and alleluia are sung in the manner of a stantipes … so that it impresses devotion and humility on the hearts of the hearers … the sequence is sung in the manner of a ductia, so that it may lead and give joy … The offertory … is sung in the manner of a ductia … so that it may encourage the hearts of the faithful to devout offering … The preface is a cantus having a light concord, as if in the manner of a ductia, composed from many verses ending in the same concord”.

In Ars musice, the musical instruments of minstrels are described positively, dance is morally beneficial, and secular music is used to explain the manner in which sacred chant is sung. In these ways, Johannes de Grocheio could not be further removed from the scathing commentators who condemn secular music and dance as sinful and devilish.

(Songs of Holy Mary), a collection of 420 songs in praise of the Virgin Mary

composed by Iberian King Alfonso X and his court, 1257–83.

Right: A five string “viella” or medieval fiddle, from The Way of Salvation

fresco in the Spanish Chapel, Florence, by Andrea di Bonaiuto, 1365.

Dominican friar and music theorist, Jerome of Moravia, wrote his Tractatus de Musica in Paris, c. 1280, for inexperienced church musicians, for “the friars of our orders or of another”, to help them understand and perform ecclesiastical chant. In the final short chapter, Jerome moved his attention from the voice to bowed strings, describing the two string “rubeba” (rebab) and three tunings for the five string “viella”, the medieval fiddle. He gave instruction on the religious and secular use of the vielle, showing that for him, his associates and those he taught, it was considered a suitable instrument for accompanying both sacred and secular music.

The treatise now known as Berkeley Ms 744, or the Berkeley theory manuscript, was probably written by French priest, Jean (Johannes) Vaillant, before 1361. It gives brief descriptions and tunings of the citole, gittern, harp, and psaltery, and is the only medieval source for the tuning of the citole and gittern.

Minstrels in paintings

It isn’t only ecclesiastical music treatises that contrast sharply with the Christian voices abhorring secular music and instruments. There is a plethora of medieval and renaissance iconography in manuscripts and paintings which show that, despite the repeated ruling of voice and organ only in the liturgy, instruments such as the lute, harp, psaltery, dulcimer and gittern were played in heaven. Below we see images from three sources, typical of the medieval/renaissance theme of the Virgin Mary or Christ/God worshipped by musicians.

Above we see two images from the Anglo-Catalan Great Canterbury Psalter (BnF Latin 8846), decorated in the first half of the 14th century. The top miniature from folio 105r shows Christ enthroned, flanked by the 24 elders of Revelation 4: 4, “Surrounding the throne were twenty four other thrones, and seated on them were twenty four elders. They were dressed in white and had crowns of gold on their heads.” It isn’t clear who the 24 elders are, but they probably represent the leaders of the church. They’re not dressed in white here, and the artist decided that all of the elders should play fiddles. Below that is folio 114r, with the blessed playing (left to right) psaltery, portative organ, fiddle, psaltery, lute, cymbala (cup cymbals), and pipe and tabor.

Above left is Mary, Queen of Heaven, c. 1485–1500, by the Master of the Legend of Saint Lucy, who operated in Bruges, Flanders. As well as multiple singers, the angels’ instruments we see, working in horizontal lines left to right, are: shawm, bray harp, another bray harp, dulcimer, lute, three shawms, shawm, vielle (medieval fiddle); trumpet (held and not played by the angel in blue on the left underneath the shawm player in white, the trumpet mostly obscured by the billowing white clothes of the angel in front); portative organ, shawm, and lute. The four singers directly behind the Virgin are singing from real and readable music, held in the hands of the two foremost angels, a variation of the motet, Ave regina coelorum / Mater regis angelorum (Hail, queen of the heavens / Mother of the king of angels), by English composer Walter Frye (fl. 1450–75).

Above right is Virgin and Child with four angels, c. 1510–15, by Gerard David of The Netherlands. It shows the holy mother and child worshipped by musicians playing bray harp and lute.

Minstrels in processions

Such artistic representations of instruments used in Christian worship were not merely symbolic.

The local municipalities of medieval Europe organised public displays of pomp and power to welcome their sovereign and royal representatives. These civic processions were elaborate pageants through the major thoroughfares, in the public square and the market place. All the local officials took part – bishops, priors, clerics, officers of administration, magistrates, guilds – all with standard-bearers and musicians. Minstrels were hired to play loud outdoor instruments, in particular shawms, drums and trumpets. Given the intimate relationship between church and state in the medieval period, this would hardly have been the case if the anti-minstrelsy clerics had held sway.

Minstrels took part in ecclesiastical pageants, too. The procession of Fête-Dieu (literally: celebrate God), which carried the sacrament through the streets, began in 1244. In 1365 in Middelbourg, The Netherlands, the sacrament was processed to the music of fiddles, gitterns, psalteries and wind instruments. In 1437 in Malines, Belgium, it was carried to the sound of fiddles, gitterns and lutes and, when the sacrament arrived at the sheriffs’ building, more minstrels on the balcony began to play. In 1442 in Germany, as the sacrament was carried into Nürnberg Cathedral, among the musicians were players of lute, portative organ and gittern, joined as they entered the cathedral by a harpist and another stringed musician.

Flemish, circa 1510–20, shows high ranking clergy and laity accompanied by minstrels

playing seven trumpets, a shawm, and another minstrel whose instrument is hidden.

The Festival of Corpus Christi was instituted by Pope Urban in 1264, to be celebrated on the Thursday after Trinity Sunday. As with Fête-Dieu, the blessed sacrament was processed through the streets. Those who participated included high and low ranking clergy, guilds, and minstrels. In 1393 in Albi, France, minstrels gave rhythm to the march and led worshippers into church. In Coventry, England, the Confraternity of Corpus Christi was established in 1348, and they arranged for the festival to be accompanied by “mynstralcy of harp and lute”, “small pypis” and “orgon pleyinge”.

On the Feast of Saint Andrew the Apostle in 1462, the head of the saint was processed to Rome. At various locations en route, boys sang dressed as angels; at other points on the way a portative organ was played and “No instrument of music was lacking”. As the procession with the sacred relic passed the house of the procurator (financial officer), music was performed by singers and players of recorders and other wind instruments.

Minstrels in churches and religious houses

Minstrels played formally in church at the ceremonial installations of high-ranking clergy. For example, in 1309 minstrels were paid to play for the installation of Abbot Ralph of Saint Augustine’s Abbey, Canterbury; in 1374 ten minstrels played for Bishop Alwyn’s installation in Winchester Cathedral; and in 1432 two minstrels played at the consecration of Prior John of Maxstoke Priory, Warwickshire.

Minstrels also played informally as acts of worship inside churches. For example, in May 1297 the minstrel Walter Lund played his harp in reverence before the tomb of Saint Richard in Chichester Cathedral, seen and heard by King Edward I (reigned 1272–1307). A few days later, Edward rewarded fourteen harpers for “making their minstrelsy before the statue of the Blessed Virgin” in the crypt of Christ Church, Canterbury – Canterbury Cathedral. The Wardrobe Books of Edward III (reigned 1327–1377) state that he made four gifts to minstrels who played before the Virgin’s image at Christ Church, the last time instructing them to play as he made his offering. Edward III also rewarded a harpist for minstrelsy in Saint Augustine’s Church, and twice made gifts to minstrels playing before the cross in the north chapel of Saint Paul’s Cathedral, London.

Religious houses paid minstrels to entertain them. Taking the accounts of Durham Abbey as an example, they record a fiddler in c. 1336; two trumpeters of the Earl of Northampton in c. 1357; a crowder in c. 1360; a piper “and other minstrels” at Christmas in 1360; a lutenist in 1361; a “jestour” – singer of stories – by the name of Jawdewyne at Christmas, c. 1362; a trumpeter, Robert, at the feast of Saint Cuthbert, 1368 or 1369; one of the king’s trumpeters in 1394–95; and a Scottish roter in 1394–95.

Right: A roter playing a rota or rotta, a triangular harp with a soundboard between two

rows of strings, from the Worms Bible, Germany, 1125–75 (BL Harley MS 2804, f. 3v).

Some abbeys and priories had minstrels in permanent employment, or took them in as residents for royal corrody, a lifetime allowance of shelter, food and clothing as reward for service at court. For example, in 1328 Edward III required that the abbot and convent of Ramsey, Cambridgeshire, provide corrody to Queen Isabella’s psaltery player, Janettus; and, in 1364, the eldest son of Edward III, Edward of Woodstock (the Black Prince), required that his trumpeter, Gilbert, be given corrody by the prior and convent of Saint Michael’s Mount, Cornwall.

High-ranking clergy employed their own personal minstrels. For example, the Bishop of Lincoln, Robert Grostest (Groosteste, Grosseteste, Grosthead), c. 1168–1253, had his own personal harper; Bishop of Durham, Antony Bek, c. 1245–1311, employed two harpers, who played at the wedding of Edward I’s daughter, Elizabeth, in 1297; both Bishop Bek and the Abbot of Abingdon brought their personal minstrels, harpers, to the celebration of Pentecost at Westminster in 1306; Thomas Percy, Bishop of Norwich from 1356 to 1369, had a harper; and of the hundreds of visits by minstrels to Durham Abbey recorded between 1278 and 1396, 32 were employed by the English royal household, 8 by the King of Scotland, 46 by lords, 8 by the town authority, and 12 by bishops. All of these high-ranking clergy’s personal minstrels were harpers, the religious symbolism of which will be described below.

The church and organised minstrelsy

Beverley, in the East Riding of Yorkshire, is a key town for understanding the relationship of the church with minstrels. Beverley Minster preserves more carvings in stone and wood of medieval musicians than any other site in Europe. They were carved between c. 1330 and the 1390s and later vandalised by Puritans and their forebears in the 16th and 17th century. Many remained partly, mostly or completely undamaged. A significant number of the broken pieces were kept, and those fragments were reinstated in the late 19th and early 20th century by John Baker, who carved new parts in stone where sections were missing and created some original works in the 14th century style.

Beverley Minster has the following numbers of musical carvings. Those too damaged to be identified are listed as such. John Baker’s original works are added in brackets (+ Baker’s number). In numerical order, there are: 10 fiddles, also known as vielles or viellas; 9 bagpipes; 8 harps; 7 portative organs; 3 shawms; 3 timbrels (+ 2); 3 psalteries; 3 gitterns (+ 2); 3 citoles; 3 pipe and tabors; 3 pairs of nakers; 3 horns, comprising 1 double oliphant and 2 long metal horns; 3 lost wind instruments; 3 lost instruments; 2 trumpets; 1 symphonie (+ 1); 1 drum; 1 pair of cup cymbals; 1 probable singer (+ 2); and 1 hunting horn (+ 1); making a remarkable total of 71 14th century images of musicians in a single church.

Representations of musicians in medieval churches are common, but such a high number needs an explanation, and we probably have one that is pertinent to our subject.

Medieval and renaissance trades had guilds, which operated as unions or associations to maintain professional standards of work and protect the interests of members. Guilds were divided into two types, merchant guilds and craft guilds. In Beverley, the craft guilds included the furbishers (armourers), porters, creelers (textile makers), mustard makers, chandlers, ropers and goldsmiths. Among them, in the 16th century, was the “Order of the Ancient Company or Fraternity of Minstralls in Beverley”. According to their one surviving document, their guild charter of 1555, it operated “between the rivers of Trent and Tweed”, i.e. south of the Humber estuary up to the Scottish border, the whole of the north east of England. Typical of guilds, they claimed ancient origins, in this case back to the 10th century, “from the tyme of king Athelstone [Æthelstan or Athelstan], of famous memorie, sometyme a notable kynge of Englande”. This suggests that the Fraternity of Minstralls was well-established in living memory in 1555, but the claim of a 10th century origin cannot be verified.

Membership of the Fraternity of Minstralls in Beverley was dependent upon being a professional musician, either a “mynstrell to some man of honour and worship,” i.e. in the pay of the nobility, “or else of some honesty and conyng as shall be thought laudable and pleasent to the hearers there or elsewhere”, i.e. freelance, “or waite of some town corporate, or other ancient towne”. At the end of the 13th century, a waite (wait, wayt, wayte) could mean a double-reed instrument of the shawm family; a player of this instrument; or a domestic or municipal watchman. By the 15th century, waite could also mean a town or city waite, a member of the band of civic minstrels, principally shawm players, paid to play at civic occasions, and this is the meaning in the minstrels’ charter. The Beverley-based minstrels’ guild, then, was for all professional musicians in the north east of England.

two humans, carved between 1330 and 1390. Photographs © Ian Pittaway.

It was standard practice that any individual or organisation who paid substantial money for the new fabric of a church building be visibly represented in it with their name or likeness. No records survive prior to 1555 of the Order of the Ancient Company or Fraternity of Minstralls in Beverley that can tell us about the 14th century carvings, but there are records of contemporaneous minstrels’ guilds, such as that in Lincoln in 1389. The potential implication is that a local minstrels’ guild in the 14th century paid handsomely towards the building of Beverley Minster in order to be so well represented. Carvings of minstrels appear on the west, north and south walls, on the tomb of the two sisters, on a capital (crown of a column), in the galleries above the nave, on the triforium (second tier gallery), the south transept (cross-piece of a cruciform church), the Percy tomb, the reredos (altar screen) and in Saint Katherine’s chapel.

The theory of minstrels partially funding the fabric of the minster gains more weight when we consider that it did happen in Beverley in the case of Saint Mary’s Church, a short walk away. Saint Mary’s has 34 musical carvings, dating from the 13th to the 16th century. Among them is the Minstrels’ Pillar, created in response to a tragedy. On 29th April 1520, the tower of Saint Mary’s Church collapsed, resulting in loss of life and structural damage to the church. The event was memorialised by an inscription on one of the pews in the nave, now kept in the priest’s room in the church: “Pray God have mace [mercy] of al the sawllys [souls] of the men and wymen and cheldryn whos bodys was slayn at the faulying of thys ccherc [church] … thys fawl was the 29 day of Aperel in the yere of our Lord 1520”. During the rebuilding work of 1520–24, among the many other donations from wealthy individuals recorded in the accounts of the Governors of Beverley was the pillar paid for by the Fraternity of Minstralls in Beverley. We see it below: on the left, a creature holding a sign reading “THYS PYLOR MADE THE MEYNSTRYLS”; right, the sign above the carved representative minstrels on their pillar.

Above we see the stone-carved Minstrels’ Pillar in its context within Saint Mary’s Church. Below is a close-up of the five minstrels. Though damaged, lacking some limbs and instruments, they have the kind of colour that once adorned all the minstrels of Saint Mary’s and Beverley Minster. This is clearly not the original paint, since it covers the broken areas. The earliest surviving descriptions of their colours are 19th century and contradictory.

The musician on the left is playing pipe and tabor, his right forearm, pipe, and left hand now lost. Next along, the position of the hands may indicate a bowed instrument, possibly a vielle (medieval fiddle), played until the mid-16th century, or perhaps a lira da braccio or, if this was an up-to-the-minute musician, a violin, which first appeared in northern Italy in 1520 and spread internationally from there. The distinct double line on the player’s chin and the position of the arms may instead indicate a wind instrument with a metal mouthpiece, such as one of the larger shawms or recorders. In the middle is a man with a line remaining down the centre of his body, indicating where the missing instrument was carved. The shape, size and position of this line and the position of the missing hands strongly suggests a harp or, less likely, a large shawm known as a bombard. The penultimate figure is playing a 5 course lute, rather old-fashioned by 1520 since the lute gained its 6th course in 1481, but certainly not impossible, and perhaps we should not take the number of courses literally. It is notable that this player is left handed, which may represent a living left-handed lutenist, but this is unlikely since these minstrels have generic faces. It is more likely that the lutenist’s image was reversed for visual balance, as a right-handed player would lead the eye towards the edge of the group rather than the centre. The final minstrel plays a wind instrument that is too broken to identify securely, most likely a shawm. If this carving of 5 minstrels represents a pipe and tabor, fiddle or large recorder, harp, lute, and shawm, then every musician has a different representative instrument.

These two churches in Beverley are clear examples of a good ongoing relationship between the church and organised minstrels. Added to the positive inclusion of a range of musical instruments in ecclesiastical music treatises, the huge number of paintings praising saints with instruments used by minstrels, the fact that minstrels were hired to play at the installation ceremonies of clergy and in religious houses, that they worshipped saints informally by playing music in church, and that clergy hired personal minstrels, it sets a radical counterpoint to the notion that the entire medieval and renaissance church considered minstrels, as a species, to be wicked, godless sinners deserving of God’s wrath. They clearly did not.

Clerical fundamentalism

In his Elucidarium, c. 1098, Christian theologian Honorius of Autun was unequivocal about the status of the souls of the variously named minstrels, jongleurs or histriones: “Do the jongleurs have any hope? None. Because they are from the bottom of their hearts the minsters of Satan.” This is in agreement with John of Salisbury, Bishop of Chartres, who, as we have seen, thought his “prince ought rather to exterminate entirely than to foster” these “human monsters”, and with Guillaume de Deguileville, Robert Curzon and the like. This radical juxtaposition between the idea of minstrels as irredeemably damned and minstrels being intimately involved in church life needs an explanation.

Some religious commentators considered music itself to be an act of sin inciting lust unless it was liturgical, focussed on Christ and the Virgin, musically undecorated, and performed only with chaste voices and the organ. For them, minstrels were sinful in and of themselves and, as we have seen, writers such as John of Salisbury justified their view with tales of real excesses by minstrels, likening them to pimps and prostitutes. But how typical were these excesses? We have three significant clues.

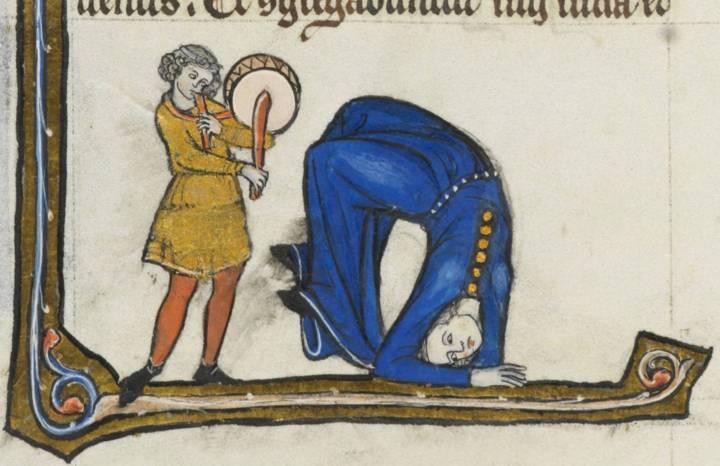

The first clue is that minstrel performances appear often and entertainingly in religious manuscripts. These artistic impressions show musicians, jugglers, tumblers, and people with performing animals, without suggesting they are doing anything improper. Indeed, as we see below left, The Decretals (decrees) of Pope Gregory IX (Smithfield Decretals, BL Royal 10 E IV, f. 58r), 1275–1325, has a page decorated with a player of pipe and tabor and a player of double pipes accompanying a tumbler and, below right, the Tiberius Psalter, c. 1050 (BL Cotton Tiberius C VI) has the holy King David playing his harp accompanied by a juggler and fiddler, hardly something we’d see if all such minstrels were considered universally immoral.

The second clue about how widespread and typical “the abuses of the jongleurs” were, whether they deserved to be called “the minsters of Satan” and “human monsters”, is in the very fact that minstrels were regularly employed by the church to play in public ceremonial acts of worship and in private entertainments. These two views can only be reconciled if we believe the clergy employing minstrels wished to show on public ceremonial occasions that they had no moral compass and lacked spiritual values, or conversely if we conclude that the censorious clergy engaged in overblown hyperbole and did not hold the mainstream view.

The third clue is from accuser John of Salisbury himself, and explains the incongruity of these opposing perceptions. In his Policraticus, c. 1159, John quotes English monastic reformer Gilbert of Sempringham (c. 1085–1190) approvingly. In 1148, Gilbert founded his own Gilbertine Order of convents, monasteries and missions, and John cites Gilbert thus: “We do not allow our nuns to sing. We absolutely forbid it, preferring with the Blessed Virgin to hymn indirectly in a spirit of humility rather than with Herod’s notorious daughter to pervert the minds of the weak with lascivious strains.” John/Gilbert is expressing the either/or dualistic view that women can either be chaste like the Virgin or else they are lascivious temptresses of men. Men will be so morally weakened, their minds so perverted, their passions so aroused by the singing of nuns that the only righteous remedy is for women to be silent. Just as the dance of “Herod’s notorious daughter”, Salome, brought about the death of John the Baptist, so women who sing “with lascivious strains” will be the spiritual death of all men.

This view of women is common in medieval Christianity. The story of The Fall in Genesis, the first book of The Bible, is that God created a paradise on Earth for Adam, the first man, and Eve, the first woman, and it was to remain so forever under one condition: they were not to eat fruit from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil. Tempted by the talking serpent in the Garden of Eden, they both ate that fruit, thus introducing sin and death into the world. No longer innocent, they became aware of their nakedness, covered up, and were banished by God from Eden. According to the influential early Church Fathers, it wasn’t Adam’s sin which brought about the Fall, it was Eve’s, and all women are daughters of Eve – sinful, sexual, tempting, ready to effect men’s moral ruin. For example, in his On the Apparel of Women, Tertullian (c. 155–c. 240) addressed every woman directly: “You are the devil’s gateway; you are the unsealer of that [forbidden] tree; you are the first deserter of the divine law; you are she who persuaded him whom the devil was not valiant enough to attack. You destroyed so easily God’s image, man. On account of your desert – that is, death – even the Son of God had to die.” In other words, the human sacrifice for sin that the Son of God made on the cross was only necessary because of the first woman, so all women are to blame for all the world’s sin and for the crucifixion of Christ. This explains why Robert Curzon, in his invective against “minstrelish little notes” in liturgical voices, railed against “masters of organum who set minstrelish and effeminate things before young and ignorant persons, in order to weaken their minds”.

Anyone who espouses such fundamentalist rhetoric will express themselves in dualistic terms, seeking enemies to damn, exaggerating what they are against, pouncing with confirmation bias upon any perceived moral breach by those they oppose, universalising it as typical of those they attack, arriving in this instance at the position that all minstrels, like all women, are the whores of Satan. We would be wise to question the veracity and accuracy of any statement describing an enemy. In this case, when a fundamentalist cleric lumps in all minstrels with “buffoons and harlots, panders [pimps] and other like human monsters” and says “the prince ought … to exterminate” them, then we know that the account will not be balanced, and any incidents of excess will be used to characterise them entirely. Such reports are not to be trusted as balanced or entirely factual accounts.

“As Dauyde seyþ yn pe sautere”: good minstrels

Sometimes the writings of medieval Christian moralists can be more subtle than they at first appear on the issue of minstrels, as we see with Handlyng Synne by English chronicler and monk Robert Mannyng, written in 1303. It is a translation into English of a book in French by the Bishop of Lincoln, Robert Grostest (Groosteste, Grosseteste, Grosthead), c. 1168–1253, called Manuel Peche, or Manuel des Peches (Manual of Sins), itself based on a work by “Wilhelm de Wadigton”, to help readers in the practice of Christian morality. Mannyng treats his source material freely, amplifying existing stories, removing those that do not fit his purpose, and adding many substantial exemplars of his own, all composed in rhyming couplets.

Mannyng and his source are against almost every activity they mention because they engage the senses in ways that excite sinful passions and take attention away from worshipping God. Mannyng disapproves of miracle plays, for example, vernacular dramas of the life of a saint (usually the Virgin or Saint Nicholas), performed by local trades guilds at festivals, calling them “a syghte of synne” and the “pompes and … werkys” of Satan because they involve “Daunces, karols [sung dances]” and “somour games,” including tournaments, competitions of the medieval martial arts: “Of many swych [such] come many shames”. He criticises clergy who participate – “More þan ouþer þey are to blame, / Of sacrylege þay haue þe fame” (“More than others they are to blame, / Of sacrilege they have the fame”) – but reserves divine vengeance for a participating minstrel:

What seye ȝe by euery mynstral

Þat yn swyche þynges delyte hem alle?

Here doyng ys ful perylous

Hyt loueth noþer Gode ne Goddys house

Hem were leuer here of a daunce

Of bost, ande of olypraunce

Þan any gode of God of heuene

Or ouþer wysdom þat were to neuene

Yn foly ys alle þat þey gete

Here clothe, here drynke, and here mete

And for swych þyng telle y shal

What byfyl onys of a mynstral

What say you of every minstrel

That delights in all such things ?

Doing this is completely perilous:

It loves neither God nor God’s house.

They would rather hear of a dance,

Of boasting and of pomp/vanity,

Than any good of God of heaven

Or other wisdom that could be mentioned.

Everything they pay attention to is in folly:

Their clothes, their drink, and their food.

And for such a thing I shall tell

What once befell a minstrel.

Mannyng follows with a story of a minstrel, taken from Bishop Robert Grostest’s text, who asked for charity at a bishop’s house. “Þys mynstral made hys melody” to entertain the bishop, who was about to eat a meal. The minstrel’s music disturbed the bishop from saying grace, so the bishop ordered that he be given charity and sent on his way, having prayed for God to kill him. The Almighty obliged by making a stone fall from a wall to strike him dead for his bad manners in disturbing the bishop and, it is implied, ultimately for being a minstrel who plays for “Daunces” and “karols”. One could easily draw the conclusion that Mannyng, in his zeal against the ungodly, included this story of a minstrel as an exemplar against all minstrelsy, but that notion is contradicted by a story of Mannyng’s own composition that follows, about Bishop Robert Grostest himself.

Bishop Grostest “louede moche to here þe harpe” (loved much to hear the harp) and had a personal harpist minstrel who resided next to his study. (We have seen above how common it was for medieval bishops to have personal minstrel harpists.) The bishop was entertained on the harp by tunes and lays (love songs). “One askede hym onys, resun why / He hadde delyte yn mynstralsy” (One asked him once, the reason why / He had delight in minstrelsy) and he replied that the skill required to master the harp “Wyl destroye þe fendes myȝt” (Will destroy the Devil’s might), for the harp, being made of wood, is likened to the cross on which Christ was crucified, so God resides in the harp, causing its hearers to lament and grieve with God on the cross, feeling his pain and his joy. He continues:

Þare for gode men ȝe shul lere

Whan ȝe any glemen here

To wurschep Gode at ȝoure powere

As Dauyde seyþ yn pe sautere

Yn harpe, yn thabour, and symphan gle

Wurschepe Gode, yn trounpes, and sautre

Yn cordys, an organes, and bellys ryngyng

Yn al þese, wurschepe þe heuene kyng.

ȝyf ȝe do þus, y sey hardly

ȝe mow here ȝoure mynstralsy.

Therefore, good men, you shall learn,

When you have any gleemen [minstrels] here,

To worship God in your poverty.

As David says in the Psalms:

A harp, a tabor, and symphonie rejoicing,

Worship God with trumpets, and psaltery,

With strings, and organs, and bells ringing,

With all these, worship the heavenly king.

If you do thus, I say vigorously,

You increase your minstrelsy.

Unlike extreme fundamentalists such as John of Salisbury, in this passage Mannyng makes clear that he did not wish God’s punishment on the minstrel who played dance music and disturbed the bishop simply because he was a minstrel, but because he played sinful dance music which promotes pride or vanity, and that minstrels who use their craft to praise God, “As Dauyde seyþ yn pe sautere” (As David says in the Psalms), are to be welcomed and enjoyed. He does so citing Psalm 150, which he would have read in a Latin translation which replaced the names of unknown musical instruments in the original Hebrew with those familiar from minstrelsy.

Three kinds of histriones

We see, then, that it was far from being the case that all medieval church authorities were against minstrels, and even some of the violent invectives against minstrelsy were qualified critiques rather than blanket condemnations. Robert Mannyng’s Christian moralising in 1303 strongly suggests he had in mind the same distinctions about minstrels made by Thomas de Chobham, Bishop of Salisbury, in the second half of the 13th century. In his Summa confessorum, Thomas stated:

“There are three kinds of histriones. Some transform and transfigure their bodies through foul movement and gesture or by baring themselves lewdly or by wearing horrible masks. All such are damnable unless they relinquish their office. Others, having no permanent abode, follow the courts of the great and amuse by satire and raillery [good-natured mockery or ridicule]. These are damnable because the Apostle prohibited communion with such and called them wandering clowns because they are useless except to devour and revile. The third use musical instruments and are of two kinds. Some of these sing wanton songs at public drinkings and lascivious congregations; they sing songs that move men to wantonness, and these are damnable like the others. There are others who are called joculatores who sing the deeds of princes and the lives of saints and give solace to men either in grief or anguish, and do not make innumerable base [shows] such as male and female dancers and others who play out indecent fantasies. According to Pope Alexander, the [second category of joculatores] is to be sustained in its profession if its members abstain from wantonness and baseness.”

and gesture or by baring themselves lewdly or by wearing horrible masks.”

Above: Tumbler accompanied by pipe and tabor, end of the 13th century, France

(Biblia Porta, U 964, f. 343v, Bibliothèque Cantonale et Universitaire, Lausanne).

Below: Gittern player accompanying dancers with and without animal masks,

Romance of Alexander, 1338–1410, Flanders (MS. Bodl. 264, f. 21v, copyright © Bodleian Library,

University of Oxford, reproduced under Creative Commons licence CC-BY-NC 4.0).

We see a similar distinction made between good and bad minstrels by minstrels themselves in the guild charter of the “Order of the Ancient Company or Fraternity of Minstralls in Beverley”, 1555. The charter states that no one may present themself as a minstrel or make money from minstrelsy except by being a member of the Fraternity and following its rules, and that if anyone “declineth from the same for lack of honest usage, that then the alderman and brethren and officers shall them expell from their brotherhood, as alderman and officers will make answer to the kyng’s officers when they speak of vagabonds and valiant beggers.” The language is important: the Fraternity want to be recognised as respectable, legitimate professionals, as with any other guild, and not have their members associated with those bad minstrels, the “vagabonds and valiant beggers”, those who Thomas de Chobham described as “having no permanent abode”. If need be, the Fraternity will call upon the force of the law: “And if any person or persons so deprived [of membership] shew himself obstinate [playing music for money without membership], and stands in contencyon arrogantly, that then the kyng’s officers be sent for to carry the offender or offenders to gaile, and there to remain until he be reconcyled to honest order, and for his obstynacy to forfeitt as th[e] alderman and his brethren think meate and convenient in that behalfe.”

We see a similar distinction made between good and bad minstrels by minstrels themselves in the guild charter of the “Order of the Ancient Company or Fraternity of Minstralls in Beverley”, 1555. The charter states that no one may present themself as a minstrel or make money from minstrelsy except by being a member of the Fraternity and following its rules, and that if anyone “declineth from the same for lack of honest usage, that then the alderman and brethren and officers shall them expell from their brotherhood, as alderman and officers will make answer to the kyng’s officers when they speak of vagabonds and valiant beggers.” The language is important: the Fraternity want to be recognised as respectable, legitimate professionals, as with any other guild, and not have their members associated with those bad minstrels, the “vagabonds and valiant beggers”, those who Thomas de Chobham described as “having no permanent abode”. If need be, the Fraternity will call upon the force of the law: “And if any person or persons so deprived [of membership] shew himself obstinate [playing music for money without membership], and stands in contencyon arrogantly, that then the kyng’s officers be sent for to carry the offender or offenders to gaile, and there to remain until he be reconcyled to honest order, and for his obstynacy to forfeitt as th[e] alderman and his brethren think meate and convenient in that behalfe.”

As we see in the article about The Garden of Earthly Delights, Bosch depicted just such a “valiant begger” in hell (detail right). His blindness is signified by his darkened eyes, his begging by the beggar’s licence in the form of a rope with a lead seal attached hanging from his begging bowl. In hell, he is reduced to turning only the crank that sounds the drone of his now giant symphonie or hurdy gurdy, making no real music at all.

The type of dishonest “vagabond” minstrels the Fraternity wish to be dissociated from are those who wander from place to place, putting on shows potentially as a front for crime, taking advantage of being unknown persons who can slip away unassociated and unidentified. Such subterfuge is represented visually in The Conjurer by a follower of Jheronimus Bosch, after 1525 (below): we see the familiar ruse of a crowd absorbed by a public spectacle as a distraction for organised theft.

Reprise

Reprise

In discussing testimonies about minstrels in the medieval and renaissance periods, we sweep together a broad and diverse group of entertainers, a period of many hundreds of years, and the whole of western and central Europe. There are bound to be contradictions and divergences. Nevertheless, a clear overall theme emerges.

Those good minstrels who, according to Thomas de Chobham, “sing the deeds of princes and the lives of saints and give solace to men either in grief or anguish”, are the minstrels who, we have seen, play Psalms, those whose instruments appear in music treatises and religious paintings, who play for the pageants of local municipalities and church festivals, who are paid to play in church at the ceremonial installations of high-ranking clergy, who are employed to entertain in religious houses, who are given royal corrody, who are employed as the higher ranking clergy’s personal minstrels, who play informally as acts of worship inside churches, whose likenesses are carved in Beverley Minster, on the Minstrels’ Pillar in Saint Mary’s Church, and in countless medieval churches. That amounts to a great many minstrels, not at all the impression given by the fundamentalist medieval clerics who would have us believe that minstrels were wholly and universally wicked, seeking to imperil the souls of the spiritually vulnerable, and were to be “totally banishe[d] from among the people of God.”

(MS. Bodl. 264, f. 97v, copyright © Bodleian Library, University of Oxford,

reproduced under Creative Commons licence CC-BY-NC 4.0).

The records plainly show that many royalty, nobility, aristocracy and clergy did not share the hard-liners’ censorious view. The social elite and high-ranking clergy continued to employ minstrels and continued to be criticised by fundamentalist clerics, but they were largely powerless to effect their disapproval. So rather than all medieval minstrels being sidelined as damned outcasts by all clergy, in most cases and places the zealots were themselves sidelined by more accepting clergy and by the general populace. The people joyfully joined in the dances, carols and miracle plays the minstrels performed for, and wanted more pleasure, more dancing, more music, more theatre than the hard-liners would ever approve of. No wonder the fundamentalists were angry and took to their pens to complain.

Coda

To conclude with a more compassionate testimony to minstrelsy, we turn to Gautier de Coincy (1177–1236), French Benedictine abbot and trouvère (the French counterparts to the Occitan troubadours), who in c. 1220 wrote Les Miracles de Nostre-Dame (The Miracles of Our Lady). Gautier took miracle stories of the Virgin, originally in Latin, and composed them in French verse, many of them set to popular secular melodies. A story he used in his collection, Le Jongleur de Notre Dame, tells of an altogether more humane approach than those strident critics above.

A jongleur who was a tumbler (acrobat) gave up his horses, clothes, money and all he had to become a monk in Clairvaux, Burgundy. Before entering the cloister, “he had lived only to tumble, to turn somersaults, to spring, and to dance. To leap and to jump, this he knew, but naught else”. When he saw the experienced monks reading and singing and didn’t know what to do, he felt lost and alone. In his despair, he avoided reading, singing, and the offices (prayers at set times), and instead crept into the crypt alone. There he saw an altar with an image of the Virgin above it, and he felt safe. However, when he heard the bell for Mass, he felt like a traitor. To compensate for his failings, he started tumbling as an act of worship in front of Mary’s image. He did this day after day, tumbling so vigorously that the floor was awash with his sweat.

Left: In the Benedictine Abbey of Saint-Martin de Savigny, Lyon, France, c. 1150–70.

Centre: The Maastricht Hours, Netherlands, 1300–25 (British Library Stowe MS 17, f. 128r),

showing a tumbler accompanied by a citole player.

Right: The Rutland Psalter, England, c. 1260 (British Library Add MS 62925, f. 65r).

“‘How to sing, or how to read to you, that I know not, but truly I would make choice for you of all my best tricks in great number. Now may I be like a kid which frisks and gambols before its mother. Lady, who art never stern to those who serve you aright, such as I am, I am yours.’ Then he began to turn somersaults, now high, now low, first forwards, then backwards, and then he fell on his knees before the image, and bowed his head. ‘Ah, very gentle Queen!’, said he, ‘of your pity, and of your generosity, despise not my service.’ … Then he threw up his feet, so that no longer were they on the ground, and he went to and fro on his hands, and twirled his feet, and wept. ‘Lady,’ said he, ‘I do homage to you with my heart, and my body, and my feet, and my hands, for naught beside this do I understand. Now would I be your gleeman. Yonder they are singing, but I am come here to divert you. Lady, you who can protect me, for God’s sake do not despise me.’ Then he beat his breast, and sighed, and mourned very grievously that he knew not how to do service in other manner.”

One of the monks decided to find out where the new monk kept disappearing to, and reported to the abbot what he saw. On discovery, the tumbler was sure the abbot would expel him from the order. “And the holy abbot turned to him and, all weeping, raised him up. And he kissed both his eyes. ‘Brother,’ said he, ‘be silent now, for truly do I promise to you that you shall be at peace with us. God grant that we may have your fellowship so long as we are deserving of it. Good friends shall we be. Fair, gentle brother, pray for me, and I will pray in return for you. And so I beseech and command of you, my sweet friend, that you forthwith render this service openly, just as you have done it, and still better even, if that you know how.’”

To add to this touching tale of love and compassion, the acceptance of the tumbler’s gifts, a last word on the matter of musical symbolism in art, just to show again that the church was not always so stern, disapproving and humourless. Between 1534 and 1536, Italian painter and sculptor Gaudenzio Ferrari created the magnificent Concert of Angels fresco on the ceiling of Sanktuarium Santa Maria delle Grazie, Saronno, Italy. The whole colourful display is seen below left. Below right is a detail. Male minstrels with bagpipes were symbolic of lust due to the instrument’s phallic shape – a large bag with a long pipe. Gaudenzio Ferrari painted an angelic female bagpiper and, bearing this history of symbolism in mind, he clearly knew exactly what he was doing.

© Ian Pittaway. Not to be reproduced in any form without permission. All rights reserved.

Bibliography

Allison, K. J. (ed.) (1989) A History of the County of York East Riding: Volume 6, the Borough and Liberties of Beverley. London: Victoria County History. Available online by clicking here.

Bowles, Edmund A. (1957) Were Musical Instruments Used in the Liturgical Service during the Middle Ages? The Galpin Society Journal, Vol. 10 (May 1957), pp. 40-56. Available online by clicking here.

Bowles, Edmund A. (1959), Once More ‘Musical Instruments in the Liturgical Service in the Middle Ages’. The Galpin Society Journal, Vol. 12 (May 1959), pp. 89–92. Available online by clicking here.

Bowles, Edmund A. (1961) Musical Instruments in Civic Processions during the Middle Ages. Acta Musicologica, Vol. 33, pp. 147-161. Available online by clicking here.

Chaucer, Geoffrey (written 1387–1400, this edition 2012) Canterbury Tales. An Interlinear Translation, Translated by Vincent F. Hopper, Revised and Expanded by Andrew Galloway. 3rd Edition. New York: Barron’s.

Clopper, Lawrence M. (2001) Drama, Play, and Game: English Festive Culture in the Medieval and Early Modern Period. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Coinci, Gautier de (originally c. 1220, this translation 1908) Of the tumbler of Our Lady & other miracles. Now translated from the Middle French : introduction and notes by Alice Kemp-Welch. London: Chatto and Windus. Available online by clicking here.

Donington, Robert (1958) Musical Instruments in the Liturgical Service in the Middle Ages. The Galpin Society Journal, Vol. 11 (May 1958), pp. 85-87. Available online by clicking here.

Erdmann, Robert G., et al. (2016) Bosch Project. Available online by clicking here.

Fischer, Stefan (2013) Jheronimus Bosch: The Complete Works. Köln: Taschen.

Grocheio, Johannes de (1270s–1300, modern publication 2011) Ars musice. Edited and translated by Constant J. Mews, John N. Crossley, Catherine Jeffreys, Leigh McKinnon, and Carol J. Williams. Kalamazoo: Medieval Institute Publications.

John of Salisbury (c. 1159) Policraticus, Book Four (selections), translated by Paul Halsall. Available online by clicking here.

Kelly, Thomas Forrest (2015) Capturing Music: the story of notation. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Mannyng, Robert (written 1303, this edition 1862) Roberd of Brunnè’s Handlyng Synne (written A. D. 1303) with the French treatise on which it is founded, Le Manuel des Pechiez by William of Waddington, now first printed from MSS. in the British Museum and Bodleian libraries. Edited by Frederick J. Furnivall. London: J. B. Nichols and Sons. Available online by clicking here.

Marijnissen, R. H. & Ruyffelaere, P. (1987) Bosch. Antwerp: Tabard Press.

Page, Christopher (1991) Summa Musice. A thirteenth-century manual for singers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Radford, Alan (transcriber) (2016) The Beverley Minstrels’ Guild. The Charter. Available online by clicking here.

Rastall, Richard (1968) Secular Musicians in Late Medieval England. A thesis presented to the Victoria University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by George Richard Rastall. Available online by clicking here.

Smith, W. C. B. (2001) St. Mary’s Church, Beverley. An Account of its Building Over 400 Years from 1120 to 1524. Beverley: The Friends of St. Mary’s Church.

Smoldon, Dr. W. L. (1962) Medieval Church Drama and the Use of Musical Instruments. The Musical Times, Vol. 103, No. 1438 (Dec. 1962), pp. 836–840. Available online by clicking here.

Smoldon, Dr. W. L. (1968) The Melodies of the Medieval Church-Dramas and Their Significance. Comparative Drama, Vol. 2, No. 3 (Fall 1968), pp. 185–209. Available online by clicking here.

Southworth, John (1989) The English Medieval Minstrel. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press.

Wyatt, Diana (2016) Making music in the North-east: waits and minstrels around the region. Available online by clicking here.

Thank you for such a well-researched and lavishly illustrated survey of musicians (and tumblers!) as they related to the medieval church. Thoroughly enjoyable!

Thank you, Will. Your comment is much appreciated. Ian

Thank you so much for your article and pictures. I lived close to Beverley until my twenties, and loved the Minster. I always wanted to know more about those merry minstrels and their strange instruments, which I was just researching. I’m glad to know they were appreciated there and at Saint Mary’s. Many thanks for your information. Jo in Canada

Hello, Jo, and thanks for your comment.

I’m currently working on a series of 8 articles exploring Beverley Minster’s medieval minstrels in depth, to go online in a month or two. There is a lot of muddled misinformation about them (including in publications the Minster’s own shop!), so my aim is to give a comprehensive and accurate commentary of their 72 14th century carved minstrels.

All the best.

Ian

I much enjoyed your very comprehensive, detailed and readable paper.

I have been looking at the 14/15c accounts of the Guild of the Holy Cross in Stratford-upon-Avon and I see that the Guild often paid a minstrel to perform at their feasts. I have been wondering what sort of music would have n been played and from your paper I imagine that ballads of the lives of saints could be a possibility. But I wondered if they allowed themselves to hear songs and tunes that didn’t have a religious connection?

Hello, Janet, and thank you for your contribution.

I would love to know more about the 14th and 15th century accounts of the Guild of the Holy Cross. I often find such accounts tantalising, as they will give information that such and such a minstrel played a specific instrument and how much they were paid, but not what they performed. The context would suggest you’re right, that an event of the Guild of the Holy Cross presupposes devotional music, perhaps of the kind harpers played before statues of the Virgin and the personal minstrels of bishops played to their employers. It’s difficult to imagine a minstrel playing secular music at such an occasion, as that wouldn’t be contextually appropriate and would lump them in with the ‘bad minstrels’ I describe above.

Where melodies alone are concerned it wasn’t always as clear cut. As I describe in this article https://earlymusicmuse.com/one-song-to-the-tune-of-another/, the same tune could be used for both secular and religious words – very handy for a minstrel playing for either sort of occasion, but perhaps carrying the danger of giving the wrong impression unless the words were sung.

All the best.

Ian

Dear Ian

Thank you very much for your reply and your very illuminating article, especially the information and the lovely clip about The Salutacyon. I can see now that it must have been devotional music that the minstrels played at the Guild feasts.

The Guild accounts are fortunately available on line:-

https://archive.org/details/stratfordonavonc00stra

Typical is the entry for 1495/6 which tells us that the ‘Mynstreles ‘ of Stratford and Warwick were paid 10d.

Incidentally, The Guild Register, which names 8000 members, includes the names of two minstrels who also joined.

On the Chapel walls we have a recently -revealed painting of two musician/minstrel-type figures and there is also (still covered by panelling) a minstrel in our Dance of Death painting.

I am a volunteer guide at the Chapel so if you are ever able to call in it would be really good to show you the painting of the minstrels. I could also tell you what we know about the hidden minstrel painting and you could look at the Guild Register.

I am often on duty on Friday mornings but can be there at many other times too, So if you would like to visit, do let me know and I’ll be there.

Janet

Hello, Janet.

Thank you so much. I’ve downloaded the Guild Register and will have a look through for any musical references.

I’ve been to the Chapel once before, some years ago for an early music concert when, if I remember rightly, the wall paintings had been recently discovered. I would love to visit again and have a detailed look. I’ll send a private email and we can arrange a time.

With my best wishes.

Ian