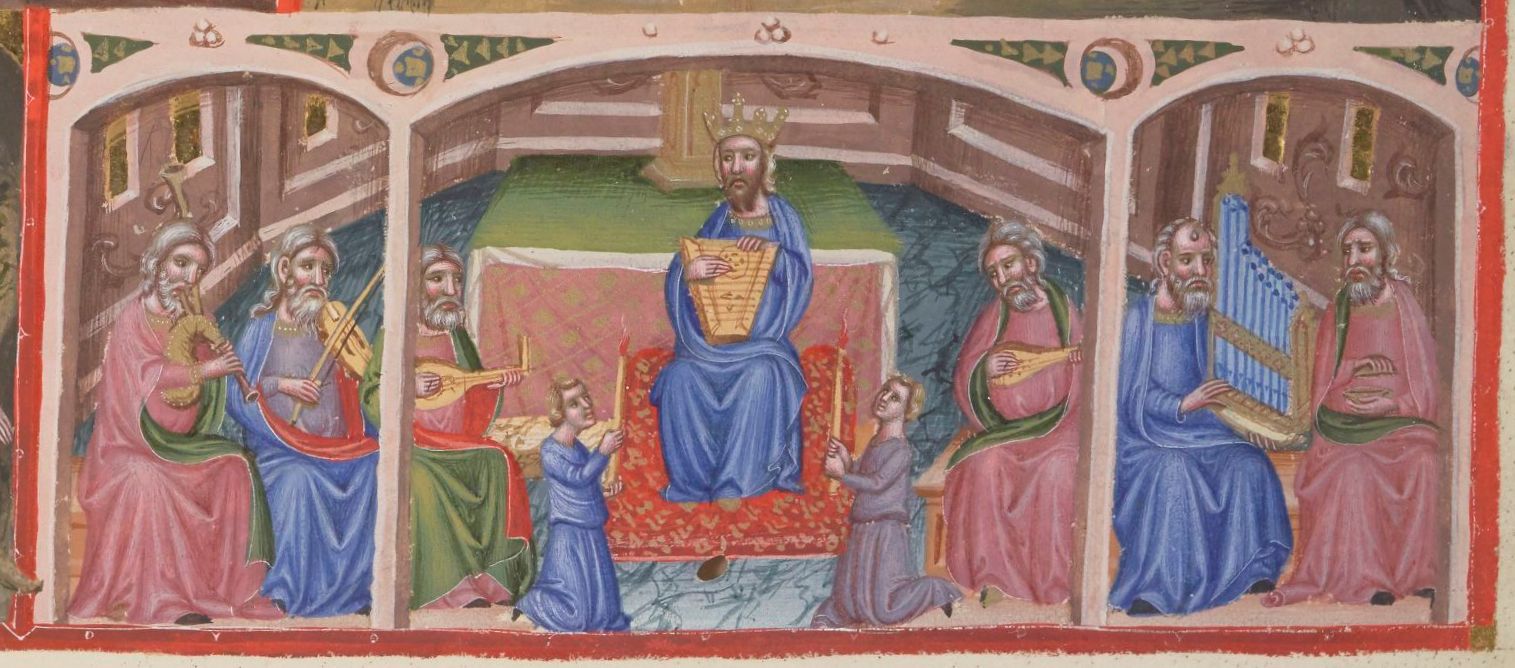

Our chief source of information for medieval musical instruments is iconography, meaning the art of manuscripts, paintings, and sculptures. That this art must be viewed critically is a commonplace understanding. Due to its highly stylised nature, some argue that all medieval iconography is suspect and of no value for gleaning real-world information. This series of articles argues that this conclusion is a mistake: if we come to iconography with an historically-informed approach, medieval art has much to teach us about historical musical instruments.

How do we judge medieval symbolism, artistic conventions and the limitations of the medium (manuscript, stone, paint) so as to gather information valuable to a luthier, a music historian and a modern player of medieval instruments? That is what this article sets out to describe, outlining 10 principles when viewing iconography for practical musical purposes.

The first article introduced the topic by outlining the characteristics of medieval art. The third and final part puts the 10 principles of the present article into practice with the recreation of a gittern painted by Simone Martini in 1312-18.