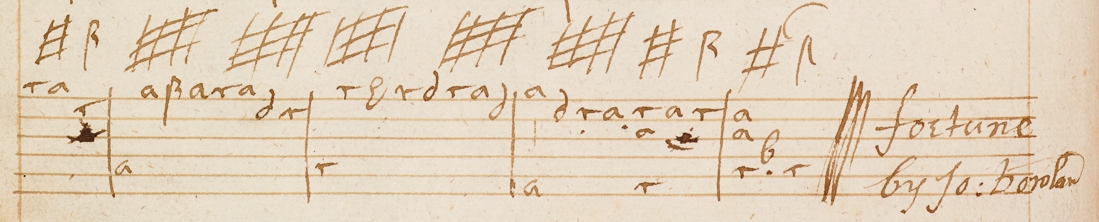

Mirie it is while sumer ilast, dated to the first half of the 13th century, is the earliest surviving secular song in the English language, preserved only by the good luck of being written on parchment, torn from a discarded book and used as the flyleaf for an unrelated manuscript. We have the music and a single verse. This may be a fragment, but its wonderful melody and poignant lyric embody in microcosm the medieval struggle to get through the winter, nature’s most barren and cruel season. This article examines the original words and notation, showing both that the now-standard version of the song performed by early music revival players is not a true representation of the text and music, and that the manuscript with the only surviving version of the song poses multiple problems of interpretation.

Mirie it is while sumer ilast, dated to the first half of the 13th century, is the earliest surviving secular song in the English language, preserved only by the good luck of being written on parchment, torn from a discarded book and used as the flyleaf for an unrelated manuscript. We have the music and a single verse. This may be a fragment, but its wonderful melody and poignant lyric embody in microcosm the medieval struggle to get through the winter, nature’s most barren and cruel season. This article examines the original words and notation, showing both that the now-standard version of the song performed by early music revival players is not a true representation of the text and music, and that the manuscript with the only surviving version of the song poses multiple problems of interpretation.

This is a second revision of the article, originally published in February 2016, revised in August 2018. This third edition is published in June 2025, with further analysis of the melody and poetry, the addition of a medieval source as the basis for interpretation of the music, and a new performance video arranged for voice and medieval harp.

We begin with a video performance of the song; followed by a translation of the Middle English verse into modern English and an exploration of its meaning; then a description of the social context of the song; and finally a step by step reconstruction of the music.