To modern ears, the most distinctive musical wind sound of the renaissance is the crumhorn, the J shaped wind cap instrument of the 15th–17th centuries. So unusual is its sound today that it was used in a Doctor Who episode to help create an unfamiliar soundscape (Doctor Who and the Silurians, 1970). In the renaissance, however, it was associated with the royal court, with ceremonial occasions and religious worship. This article briefly traces its history, and its perhaps surprising link with the bagpipes. With three accompanying videos: a crumhorn / lute pairing; the sound of the crumhorn’s probable predecessor, the bladder pipe; and a pavan played by a crumhorn consort.

To modern ears, the most distinctive musical wind sound of the renaissance is the crumhorn, the J shaped wind cap instrument of the 15th–17th centuries. So unusual is its sound today that it was used in a Doctor Who episode to help create an unfamiliar soundscape (Doctor Who and the Silurians, 1970). In the renaissance, however, it was associated with the royal court, with ceremonial occasions and religious worship. This article briefly traces its history, and its perhaps surprising link with the bagpipes. With three accompanying videos: a crumhorn / lute pairing; the sound of the crumhorn’s probable predecessor, the bladder pipe; and a pavan played by a crumhorn consort.

Crumhorn played by Andy Casserley, lute by Ian Pittaway, together as The Night Watch,

playing their arrangement of the 16th century French traditional song/dance,

Quand je bois du vin clairet / When I’m drinking claret.

Origins

The crumhorn seems to have originated in Germany, its name derived from the variously spelt crum, krumm or krumb meaning crooked, curved or bent, and horn (meaning horn). Its musical associations, historically, are largely with Germany, Italy and the Low Countries (a European coastal region at or below sea level, especially the Netherlands and Belgium).

The first definite record of crumhorns are the Krummpfeyffen, meaning curved/crooked pipes, at the 15th century court of Albrecht Achilles of Ansbach (reigned 1440–1486), in what is now Germany. No image of these instruments has survived. The first surviving crumhorn iconography is from Italy, in Lorenzo Costa’s painting, The Triumph of Death, 1488–90. Trying to find it in the small detail of a huge and complex painting, with its biblical scenes, crowds, animals, air-borne saints and angels and figures of death is like a music-related version of Where’s Wally?, so I’ve given you the answer in the picture below.

Right: The small detail in the bottom right corner of a seated vielle player and, on his right,

a small child holding a crumhorn. (As with all pictures, click to enlarge in a new window.)

The crumhorn is a reed cap instrument, meaning that the player’s lips do not make direct contact with the reed, as they do with a shawm or a modern oboe: instead the crumhorn’s double reeds, made of cane, are capped inside a wooden mouthpiece, thus the player makes lip contact with the wood; and because the reeds are capped, the player has little volume control and needs to exert considerable breath pressure in order to play cleanly.

Though the renaissance crumhorn first appeared at the 15th century German court, the word Krummhorn was used in medieval Germany from c. 1300, indicating a probable predecessor and developmental line. The earlier Krummhorn had no wind cap, so players placed their lips directly on the reed. Like the renaissance crumhorn, it was curved (as one would expect, given the name), a feature which itself implies an origin from the use of an animal horn, such as we find with medieval bladder pipes. The only explanation for the musically and technically unnecessary bending of the wood into the distinctive bend seems to be this shape-matching of the crumhorn’s developmental origin.

in praise of the Virgin Mary. Its author, Alfonso X, ruled regions now in Spain and Portugal.

Right: A bladder pipe from the Heidelberger Totentanz, 1488, a German book of 38 prints

from woodcuts, author unknown, depicting the dance of death.

You can see and hear a bladder pipe being played by clicking here.

Elevated status

The first extant recorded appearances of the renaissance crumhorn at the royal court of Ansbach and in Lorenzo Costa’s painting already indicate its elevated status, and other examples confirm it.

Four crumhorns and other instruments accompanied the Mass at the wedding of Duke Johann of Saxony to Sofia of Mecklenburg at Torgau in 1500.

among other instruments, a crumhorn on the table.

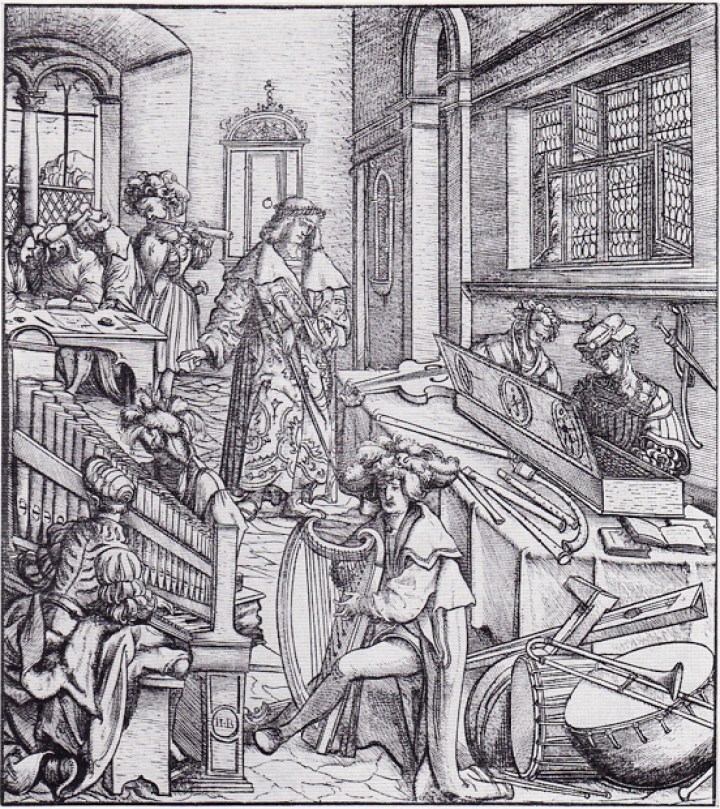

Holy Roman Emperor, Maximilian I (1486–1519), wrote Der Weisskunig (The White King) with his secretary between 1505 and 1516. This thinly-disguised idealised autobiography includes woodcuts by Hans Burgkmair, one captioned ‘How the young white king learned to know music and string playing’, shown above. We see Maximilian surrounded by musicians and instruments, including a harp, lute, tromba marina, sackbut and, on the table, a crumhorn.

In 1516-18, Maximilian commissioned Triumphzug (The Triumphal Procession or The Triumph of Maximilian), a series of woodcuts by several artists. It was again Hans Burgkmair who created the image depicting Hans Neuschel, court sackbut player and leader of the court wind band, with a group which comprised his sackbut plus 2 shawms and 2 crumhorns.

woodcut by Hans Burgkmair for Maximilian I’s Triumphzug, 1516-18.

Heinrich Aldegrever, from his series of 1551,

The Small Wedding Dancers, depicting three town

pipers in livery cloaks and badges playing crumhorns.

(As with all pictures, click to enlarge the

picture in a new window.)

In England, an inventory of instruments on the death of King Henry VIII in 1547 shows that, amongst his varied and impressive collection, he owned 11 crumhorns – or possibly 18, if the 7 ivory “crok horns” were also crumhorns – which indicates that they were played at his court. The Earl of Arundel also owned crumhorns, and poet and composer Sir William Leighton (fl. 1603–1614) at least knew of them, mentioning “Crouncorns” among other instruments in his paraphrase of the Psalms in his song book, The Teares or Lamentations of a Sorrowful Soule, 1613.

A print by the German painter and engraver, Heinrich Aldegrever, in his 1551 series, The small wedding dancers, shows 3 crumhorn players wearing livery cloaks and badges, worn to indicate employment and allegiance (shown on the right). Given that they’re musicians, this would signify that they’re town pipers, Stadtpfeifer, employed by the town council to perform at official occasions, weddings, baptisms, royal visits, and so on, with the exclusive right to provide official music within the boundaries of the town or city. In England, such municipal bands were known as the waits.

Music

During this period there are only limited instances of written music specifying crumhorns (the reason for which is discussed below). Some examples:

Thomas Stoltzer (also Stolczer or Scholczer, c. 1480–1526) was a German composer who noted that his setting of Psalm 37, Erzürne Dich Nicht (Fret Not Yourself), written in 1526, may be played with crumhorns (except for the soprano part, which occurs only in the last movement). From a surviving letter in his hand, it appears that the motivation behind this setting was to enjoy favour so as to join the court of Duke Albrecht of Prussia in Königsberg. However, Stoltzer died shortly afterwards.

Francesco Corteccia (1502–1571), one of the best known early Italian madrigalists, was court composer for Cosimo de’ Medici, required to compose for lavish and spectacular court entertainments, with a huge array of instruments and elaborate costumes. One such event was the wedding of Duke Cosimo to Eleonora di Toledo in 1539, for which Corteccia wrote a set of 7 madrigals, including Guardan almo pastore, indicating that its 6 part voicing was to be repeated, doubled by crumhorns.

German musician, Johann Hermann Schein (1586–1630), composed his Banchetto musicale (Musical banquet) in 1617, probably as dinner music for the courts of Weissenfels and Weimar. It includes 20 variation suites, one of the earliest works of its kind, ending with a Padouane (Pavane) “à 4 Krumhorn”, which you can see and hear performed by clicking here.

Musical context

So we see that crumhorns were played for religious, royal and municipal occasions, and for court entertainments. The crumhorn seems to have been reserved exclusively for these contexts. In 15 inventories of musical instruments which specifically include crumhorns, dated between 1518 and 1593, from Italy, Flanders, England, Germany and Spain, all of the crumhorns were owned by royalty, by cathedrals, by noblemen, or by the waits, the municipal city bands (known as piffari in Italy and Stadtpfeifer in Germany). There are no examples of any musician either owning or playing a crumhorn in any country who was not either a professional court or municipal musician or a member of the aristocracy. No household books include music for it, as we have for the lute, cittern and bandora, and no music for private consumption was published for it, as it was for the lute, viol, violin, 4 and 5 course guitars, cittern and bandora. Even in the court, there appear to have been no crumhorn specialists, as there were, for example, lutenists: it seems to have been one of many instruments the court required a versatile multi-instrumentalist employee to play.

showing the crumhorn in a religious setting, with a lutenist and a viola da braccio player.

(Click to see larger in a new window, click in new window to further enlarge.)

It seems to be for this reason that, while there are many contemporaneous representations of shawms, sackbuts, lutes, and so on, crumhorns are more difficult to find: its status was both elevated and restricted. This is attenuated by the fact that the geographical reach of the instrument was small, limited largely to Germany, Italy and the Low Countries. In England, for example, though Henry VIII and the Earl of Arundel owned crumhorns, there are no records of anyone else doing so and no images; and whereas Heinrich Aldegrever showed German waits playing crumhorns, the instrument does not appear in the inventories of English waits. It was known in France as the tournebout, meaning ‘the turned up end’, with only 3 references: illustrated in Marin Mersenne’s Harmonie universelle, 1636; referred to by Pierre Trichet in his Traité des instruments de musique, c. 1640; and by the time Denis Diderot published his Encyclopédie, 1765, he described it as an “instrument ançiens”.

The crumhorn consort

Like recorders, viols and lutes, crumhorns were made in a range of sizes and therefore pitches, meant to be played together as a consort. The German musical treatises of both Sebastian Virdung (Musica getutscht, 1511) and Martin Agricola (Musica instrumentalis Deudsch, 1529) describe crumhorn consorts of 4 instruments in 3 distinct sizes and pitches: 1 descant in g, 2 tenors in c (also called alto-tenors or tenor-altos), and 1 bass in F. It may be that the creator of the woodcut illustrations was confused by 4 instruments in 3 sizes, since both Virdung’s and Agricola’s pictures (the latter clearly copied from the former) show 4 sizes, not supported by the text.

Left: From Sebastian Virdung, Musica getutscht, 1511, showing 4 crumhorn sizes,

though the text describes only 3. Next to them is a “Platerspil”, a bladder pipe.

Right: Illustrations identical to Virdung but reversed in Martin Agricola,

Musica instrumentalis Deudsch, 1529, also with a “Platerspiel”, a bladder pipe.

numbers his illustrations: 1. the mysterious

“Bassett: Nicolo”, an otherwise unknown

instrument whose identity and very existence is

now debated, but which appears to be a hybrid

of the extended bass crumhorn and bassett

(between tenor and bass) shawm;

the crumhorn consort; 3. cornetts; 4. bagpipes.

One concern of musicians and instrument-makers ever since the beginning of the renaissance was to extend the pitch range of their instruments. The crumhorn generally has a range of only an octave and a note. An extra three notes above an octave plus one are possible with extreme effort, but controlling those notes is so difficult that you’ll rarely find a crumhorn player prepared to do it. Under-blowing can extend the range of the crumhorn with lower notes, but this is only possible on large crumhorns. So since the pitch of a crumhorn could not be extended, together the consort of different sizes hugely increased the range of music that could be played, and the way to extend the pitch range further was to add a larger and smaller instrument to each end of the consort.

Michael Praetorius, in his Syntagma musicum II, 1619 (3 volumes, 1615–1620), described just such an extension, adding the great bass to the bottom and the small descant or exilent to the top. The exilent may not have been a new innovation. Francesco Corteccia’s madrigal of 1539, Guardan almo pastore, specifically required the stortina, a small crumhorn. Was this the same as Praetorius’ exilent? It may be that Virdung’s and Agricola’s illustrations showing 4 sizes of crumhorn were indeed correct, the text omitting the highest pitched instrument.

Praetorius proposed a crumhorn consort of 9 players: 1 exilent, 2 descants, 3 tenor-altos, 2 basses, and 1 great bass. Again, this may not have been new when he published in 1619: in 1539 the Bavarian city of Nuremberg bought a set of 9 crumhorns for its waits, their municipal musicians.

The crumhorn’s cousin, the cornamuse, and their link with bagpipes

The crumhorn had a cousin, the cornamuse. Like the crumhorn, the cornamuse seems to have been German in origin, since Michael Praetorius was the only person to describe it. He did so as follows:

“Cornamuse are straight … They are covered below, and … have several little holes, from which the sound issues. In sound they are quite similar to crumhorns, but quieter, lovelier, and very soft. Thus they might justly be named still, soft crumhorns.”

and the only reference to the instrument is by Michael Praetorius in 1619.

Andy Casserley playing Quodling’s Delight a.k.a. Goddesses,

traditional, early 17th century, on cornamuse.

As Praetorius described it, the cornamuse was essentially a straight crumhorn and therefore, presumably, shared the same repertoire. Due to lack of evidence for its wider use or longevity, with no surviving instruments and no iconography, its popularity appears to have been local and short-lived; whereas the crumhorn’s continued use lasted until the middle of the 17th century.

Praetorius’ wind cap cornamuse shares the same name as the Italian cornamuse and the French cornemuse, both meaning bagpipes. We have to be cautious about linking them, since there are many examples in early music of different-naming of the same instrument – the crumhorn being a case in point, known in France as the tournebout – and the same-naming of very different instruments – the gittern, for example, over time meant a medieval bowl-back quill-played instrument, the renaissance 4 course guitar in England and France, and a small, wire-strung cittern in baroque England, all sharing the same name, all quite different. With the wind cap cornamuse and the bagpipes, the same-naming appears to signify real organological as well as etymological links.

Their mutual etymological origins are in the Latin cornu, horn, and musa, literally meaning wind, but since the writing of German music theorist Regino von Prüm in the 9th century musa has also meant music, and since the writing of English music theorist Johannes Cotto (working in Germany), c. 1100, it has also come to mean specifically bagpipes. Indeed, one name for the crumhorn in Italy was cornamuto torto, which can be read literally and prosaically as horn wind crooked or horn music crooked; but since cornamuse was the name for Italian/French bagpipes, I don’t think it would be pushing it to too far to read Praetorius’ cornamuse as a deliberate linguistic nod in bagpipes’ direction.

Here’s why. The crumhorn, cornamuse and bagpipes have in common a cylindrical bore, meaning that their tubes are parallel (as distinct from a conical bore, which gradually widens). The effect is to give them all a range of only 9 notes and essentially the same method of note production. Crumhorn and cornamuse players blow into the wind cap for the reeds to vibrate, without touching them directly; bagpipers blow into the mouthpiece for the reeds to vibrate, without touching them directly, which also has the effect of filling the airbag to produce a continuous sound. Remove the airbag and drones from a bagpipe, assemble what you have left, and you have a wind cap cornamuse; bend it to a J shape and you have a crumhorn.

The end

The end of the crumhorn came in the middle of the 17th century as a result of changing musical tastes. Since instrument makers, composers and players had long been expanding their pitch range, it’s a testament to the distinctive sound of the crumhorn that it lasted as long as it did with only 9 notes. Here’s one last burst of that wonderful sound.

La Volta, traditional 17th century, from Michael Praetorius’ compendium of dance music,

Terpsichore, 1612, played on crumhorn by Andy Casserley.

© Ian Pittaway. Not to be reproduced in any form without permission. All rights reserved.

Thanks for an interesting history. It is good to hear that even back then the krumhorn was a minority interest. I have a couple of questions:

1. how is it possible to some of the lower crumhorns can “underblow”: an F instrument can blow (with careful breath control!) a C below the F.

2. you didn’t mention the Rauschpfeife. Is that related? It’s also a capped reed, but otherwise functions quite differently.

Hello, Vic. Under-blowing can extend the range of the crumhorn with lower notes, but this is only possible on large crumhorns. I don’t think the rauschpfeife is in the same family as the crumhorn. Though both rauschpfeife and crumhorn are reedcaps, the rauschpfeife has a conical bore and the crumhorn a cylindrical bore, so the rauschpfeife is more like a windcap shawm.

The psalm by Stoltzer ist No. 37 (not 27). And: the whole piece has to be transposed down a fourth; the fact that Stoltzer said the soprano part doesn’t fit the range of a crumhorn only shows that he was not aware of the instrument: Obviously they were very rare; only three (or so) survived.

Thank you, Uwe. I have corrected the psalm number.

All the best.

Ian

What an extraordinary history to my favourite instrument! how fascinating!!! I am going to the Royal Conservatoire of crumhorns to study, wish me luck fellow crumhorners! Find out more about my crumhorn experience by my website.

Cordially

Hamish D G H Pa