One of the earliest extant pieces of English instrumental music has survived with the 13th–14th century manuscript, Douce 139, now in the Bodleian Library, Oxford. It is exciting in its musical drive and complexity, but interpretation of the neume notation has its problems, leaving us to make judgements about intention. The music is untitled, and is often named Estampie or English Dance in modern sources.

One of the earliest extant pieces of English instrumental music has survived with the 13th–14th century manuscript, Douce 139, now in the Bodleian Library, Oxford. It is exciting in its musical drive and complexity, but interpretation of the neume notation has its problems, leaving us to make judgements about intention. The music is untitled, and is often named Estampie or English Dance in modern sources.

This article works through the puzzles to gain performable answers. What is an estampie? Is the Douce 139 piece an estampie? Was the estampie really a dance? How can the musical problems left by the scribe’s imperfect notation be reconciled? This article looks for historically informed solutions, with a video of the music played on citole.

This is a revised version of an article first published in February 2019, with a more detailed analysis of the music and a new performance video.

An untitled instrumental piece from c. 1270 in the English manuscript,

Douce 139, often titled Estampie or English dance in modern editions,

played by Ian Pittaway on citole.

Some aspects of the music are inconsistent and subject to interpretation,

as described in the video above and the article below.

(Citole based on the British Museum citole, commissioned by Ian Pittaway, made by Paul Baker.)

The manuscript

(As with all pictures, click for larger version.)

Francis Douce (pronounced Douse), 1757–1834, was an English antiquarian who collected manuscripts, prints, books, drawings, coins, and games dating from the 8th to the 19th century. On his death he bequeathed his collection to the Bodleian Library, Oxford, including a manuscript catalogued as Douce 139. We can be sure it dates from the late 13th to mid 14th century since specific dates are mentioned: 1286–1307, 1303, 1332 and 1352. The document comprises statutes from various towns; other legal matters; items relating to Coventry, such as gifts of land and letters to and from the prior of the Benedictine Priory of Coventry Cathedral, including the only known record of the death of its 11th century founder, Countess (now referred to as Lady) Godiva; and verses on love in three languages. There are also some leaves of music, not integral to the manuscript, all written out by the same scribe: Foweles in þe frith for two voices (about which there is an article here), a three voice French motet (Au queer / Ja ne mi / Joliettement), and the mostly monophonic melody which is the subject of this article, which fits the rubric for being an estampie. The notation for the music suggests a date circa 1270, slightly earlier than the earliest date in the main body of Douce 139.

Is the Douce 139 piece an estampie?

The piece at folio 5 verso, without title in the manuscript, is often called Estampie or English dance in modern sources. The estampie, its Old French and Middle French name, was a popular musical form of the 13th and 14th centuries, called estampida in Occitan, istanpitta or stampita in Tuscan, and stantipes, stantipede, stantipedem, stantipedis, stampania, or stampetum in Latin.

If we are judge whether the untitled instrumental in Douce 139 is an estampie, we must first define our terms. An article to be published on this site in 2025 will look at all the surviving historical evidence for estampies and existing estampie music, and delineate four types. In summary, three features define the form and unite all types of estampie. The first is the double versicle, a term taken from the liturgy in which the celebrant or cantor sings a line and the congregation sing a response back. In the estampie, this typically means there is a musical phrase followed a response, the open ending (1st time bar in modern terms), then the same musical phrase again followed by a close ending (2nd time bar in modern terms). The second feature is that the open and close endings begin with the same notes as each other then diverge. The third feature is that there is no standard phrase length for either the call or the response of the double versicle, so the only element that gives the piece shape is the open and close ending.

With this as the foundation, surviving examples show us that there were four types of estampie.

i. stanzaic estampie

There were sung estampies and instrumental estampies: the stanzaic form only occurs with sung estampies. The music of each stanza is the same, which means that each stanza is a complete estampie. The earliest surviving estampie is in the stanzaic form: the tune to the song, Kalenda maya, with words by the troubadour Raimbaut de Vaqueiras, fl. 1180–1207, set to the melody of an estampie played on vielles (medieval fiddles) by visiting French jongleurs at the court of Montferrat in northern Italy where Raimbaut was serving. (Jongleurs were itinerant entertainers who performed music, juggling, acrobatics, and recitation.)

ii. consecutive or linear estampie with fixed open and closed endings

In an estampie we may call consecutive or linear, each unit of new musical material, beginning with material A, has an open ending, x, then A repeats leading to a close ending, y. This musical unit, akin to a double versicle, may be written AxAy. This unit of music is called a punctus (pl. puncta) by Parisian music theorist Johannes de Grocheio (or Grocheo) when describing the estampie in his Ars musicae (Art of music), c. 1300. The next punctus is new material B with the same open and close ending as before, which may be written BxBy; and so on for as many consecutive or linear puncta the estampie has, with the same open and close ending each time. If there are four puncta, for example, the form would be AxAy BxBy CxCy DxDy. The eight French royal estampies of Manuscrit du roi, c. 1300, are all of this type. As with all estampies, neither the length of the punctus, the length of the open ending or the close ending, nor the number of puncta is fixed.

iii. consecutive or linear estampie with mixed open and closed endings

This is the same as type ii, except that the open and close ending changes during the piece. As we will see below, the untitled English estampie of Douce 139 is of this type.

iv. compound estampie

Types ii and iii are consecutive or linear, i.e. each consecutive punctus has new material before the open and close ending, progressing in a linear fashion. The eight Italian istanpittas of British Library Add 29987, c. 1400, are examples of a different type: compound estampies, i.e. each punctus after the first starts with new material, then repeats a section or several sections of material from a previous punctus before the open and close ending. There is no fixed compound pattern, other than that the new material comes first in each punctus, and each punctus is given shape by the open and close ending. To take two examples from BL Add 29987, the form of Tre fontane is

ABCDxABCDy EBCDxEBCDy FCDxFCDy GDxGDy

and the form of Ghaetta is

ABCxABCy DECxDECy FECxFECy GBCxGBCy

Was the estampie a dance?

The aforementioned Parisian music theorist, Jean de Grouchy, better known by his Latinised name, Johannes de Grocheio (or Grocheo), wrote in Ars musicae that the estampie is irregular and complicated, requiring concentration from both performer and listener. The name of this musical form given by Grocheio is stantipes or stantipedes, Latin for standing feet. The assumption of almost every modern writer is that the estampie/stantipedes was a dance. Inasmuch as all dances are performed standing up, this doesn’t tell us a great deal, unless we understand it to mean standing on one spot. In Spanish, la estampida is a stampede, which may give us a clue if we suppose the estampie was a dance: paintings from the period indicate that one dance may have involved stamping, which is one way of interpreting the painting below: a shepherds’ dance in an antiphonal missarum from Poitiers, 1485 (Bibliotheque nationale de France MS Lat. 873, folio 21r). However, all historical data refutes the idea that this could be a stamping estampie: the joining of hands indicates a carol; this is 45 to 55 years after the last written evidence of the estampie; no manuscript with estampie music states that it was danced; and there is no historical evidence that the estampie was a dance.

Swimming against the tide of almost all previous attempts to describe the estampie form, Christiane Schima (Die Estampie, thesis at Utrecht University, 1995) put aside modern assumptions and surveyed all the available historical evidence. She concludes that the estampie was not a dance, but a vocal and instrumental musical form for a listening audience. For example, French court historian Jean Froissart made a distinction between the estampie and the carol in his L’espinette amoureuse, written 1365–72: “And as soon as [the minstrels] had stopped the estampies that they beat, those men and women who amused themselves dancing, without hesitation, began to take hands for carolling.” Taken in isolation, this may mean that dancers performed estampies without joining hands, then joined them for the carol. Other accounts make the meaning clear. For example, in his poem, Remède de Fortune, French poet and composer Guillaume de Machaut (c. 1300–1377) describes a lavish entertainment in which first the company are observers and listeners, entertained by minstrels playing estampies, and then they become participants in dancing plus, in Machaut’s account, “games, singing, and music”. In Remède de Fortune the division between non-participatory and participatory entertainment is especially clear, and estampies are unambiguously played by minstrels for listeners, not dancers. In Christiane Schima’s study, every medieval reference to the estampie follows the same pattern, yielding no historical evidence that it was a dance form.

Swimming against the tide of almost all previous attempts to describe the estampie form, Christiane Schima (Die Estampie, thesis at Utrecht University, 1995) put aside modern assumptions and surveyed all the available historical evidence. She concludes that the estampie was not a dance, but a vocal and instrumental musical form for a listening audience. For example, French court historian Jean Froissart made a distinction between the estampie and the carol in his L’espinette amoureuse, written 1365–72: “And as soon as [the minstrels] had stopped the estampies that they beat, those men and women who amused themselves dancing, without hesitation, began to take hands for carolling.” Taken in isolation, this may mean that dancers performed estampies without joining hands, then joined them for the carol. Other accounts make the meaning clear. For example, in his poem, Remède de Fortune, French poet and composer Guillaume de Machaut (c. 1300–1377) describes a lavish entertainment in which first the company are observers and listeners, entertained by minstrels playing estampies, and then they become participants in dancing plus, in Machaut’s account, “games, singing, and music”. In Remède de Fortune the division between non-participatory and participatory entertainment is especially clear, and estampies are unambiguously played by minstrels for listeners, not dancers. In Christiane Schima’s study, every medieval reference to the estampie follows the same pattern, yielding no historical evidence that it was a dance form.

Questions of interpretation

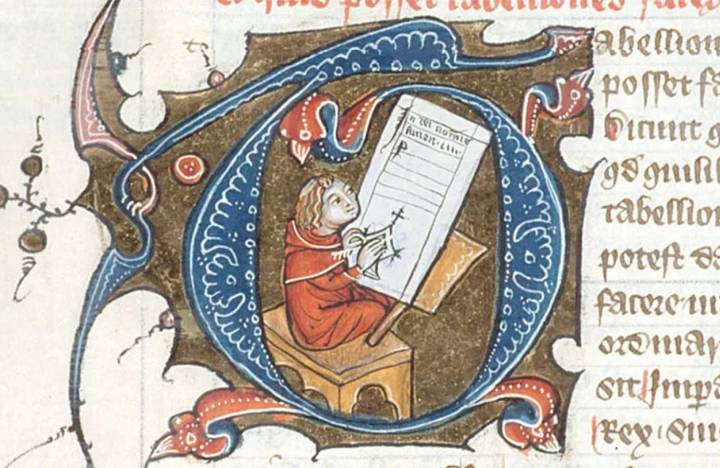

English estampie. Thank you to the Bodleian

Library for permission to use this image,

which is © Bodleian Library.

(As with all pictures, click to enlarge in a new window,

click in new window to further enlarge.)

To make this estampie playable, there are some issues of interpretation due to the scribe not always being clear about musical intention. The manuscript page is reproduced on the right, and below is an annotated version.

In the commentary that follows, each section of music is presented in turn, in the original neumes and in modern notation, so the reader can see exactly what is being discussed. The complete music in modern notation is at the end of this article. It includes a fixed Bb, as written in the manuscript, and does not include a time signature: there are no time signatures in neume notation, and putting the music in modern 3/8 or 3/4 time would be musically misleading. Instead, there are bar lines to indicate each perfection – a unit of 3 beats – and the open and close endings are shown as 1st and 2nd time bars.

General comments

For clarity, below I have marked the beginning of each punctus or section with a letter: 10 puncta, marked A to J.

The neume notation is written clearly, but there are several errors. We see rubbings out and corrections in puncta B, E, G, H, I and J. The halves of puncta F and I are split on two parts of the page, both half-puncta written after the end of the piece. Unique of all surviving estampie music, instead of writing out the music for the section or punctus, followed by the open ending then the close ending, repeated music is written out in full, but inconsistently.

(As with all pictures, click to enlarge in a new window, click in new window to further enlarge.)

Punctus A

As just noted, the punctus is written out in full in the manuscript. My added downward-pointing black arrow on the annotated manuscript page indicates the point at which the music returns to the beginning of the punctus. The unmarked open ending therefore begins at some point before this. The downward-pointing red arrow indicates the point at which the ending diverges from the melody of the first half. The point at which the open and close endings begin is not indicated in the music. To discern this, I have followed the way other surviving estampies are written: the open and close start with the same notes at the beginning of a phrase, then diverge, as shown in my modern transcription.

Punctus A is completed in the close ending with a perfect longa on f’, 2 short vertical lines indicating a caesura, another perfect longa on f’, and 4 short vertical lines (see right). The final 4 lines indicate the end of the puncta each time they appear, with the exception of punctus B, which ends with 2 lines and punctus G, which ends with 3. The latter are clearly not musically meaningful, just inconsistencies in the scribe’s writing along with other inconsistencies: the rubbings out and the forgotten two half-puncta added to the end of the music. What the 2 line caesura between the final 2 notes indicates is not clear. It may be intended to show that the penultimate longa is stopped short or imperfect, 2 beats and a rest rather than 3 beats. Theoretically, it could indicate that at this point we return to the beginning of the punctus and play it again, terminating in the final note between the 2 lines and the 4 lines, but this is highly unlikely since the scribe has already fully written out a clear unit of music with an open then a close ending, a complete punctus as defined by Johannes de Grocheio in his description of the estampie. I leave open the question of the meaning of the caesura, and interpret the ending as 2 consecutive f’ notes.

Punctus A is completed in the close ending with a perfect longa on f’, 2 short vertical lines indicating a caesura, another perfect longa on f’, and 4 short vertical lines (see right). The final 4 lines indicate the end of the puncta each time they appear, with the exception of punctus B, which ends with 2 lines and punctus G, which ends with 3. The latter are clearly not musically meaningful, just inconsistencies in the scribe’s writing along with other inconsistencies: the rubbings out and the forgotten two half-puncta added to the end of the music. What the 2 line caesura between the final 2 notes indicates is not clear. It may be intended to show that the penultimate longa is stopped short or imperfect, 2 beats and a rest rather than 3 beats. Theoretically, it could indicate that at this point we return to the beginning of the punctus and play it again, terminating in the final note between the 2 lines and the 4 lines, but this is highly unlikely since the scribe has already fully written out a clear unit of music with an open then a close ending, a complete punctus as defined by Johannes de Grocheio in his description of the estampie. I leave open the question of the meaning of the caesura, and interpret the ending as 2 consecutive f’ notes.

There is a contextual reason for interpreting the ending as 2 consecutive f’ notes: having the final note play twice is a typical feature in the close ending of an estampie. In the eight French royal estampies of c. 1300, the final note of the close ending is played twice in every one. In the Italian istanpittas of British Library Add 29987, c. 1400, the final note of the close ending is played twice in 6 out of 8 pieces (or possibly 6 out of 10 pieces, depending on how we count the istanpittas – this will be explored in an article in 2025 considering all medieval evidence for the estampie form). The English estampie of Douce 139 has 10 puncta and therefore 10 close endings. If we interpret the fully written out puncta as complete and therefore not to be repeated, and we interpret the last 2 notes played consecutively as just described, then we have a double final note in 6 out of 10 endings, and the final note is played 7 times in punctus H, and 5 times in puncta I and J.

Punctus B and C

All the same points apply to puncta B (above) and C (below) as to punctus A: the scribe wrote the music in full; I have annotated the manuscript with black arrows to show when the music begins to repeat and red arrows for the notes beyond the repeat, i.e. the last notes of the close ending; and the caesuras at the end are treated in the same way.

What is unique about punctus A, B and C compared to any other estampie is that they are identical except for the opening notes. This is somewhat like the compound estampie – my estampie type iv above – in that puncta B and C start with new material, then repeat material from punctus A before the open and close ending. The true compound estampie has a more complex form, such as Tre fontane – ABCDx ABCDy EBCDx EBCDy FCDx FCDy GDx GDy – whereas this estampie changes only the opening notes in the first three puncta; and the repeated material in puncta A, B and C does not reappear thereafter. In all other respects, this estampie is my type iii, a consecutive or linear estampie with mixed open and closed endings, as the open and close endings of the first 3 puncta are not repeated in subsequent sections.

Punctus D

From this point, each punctus has only new material, as we would expected in a consecutive or linear estampie. In estampie type iii, with mixed open and close endings, we would usually expect that the new open and close of punctus D would repeat in some of the subsequent puncta: instead, from here the open and close are different each time, with punctus G and H having no distinct open and close.

In puncta A, B and C, the open and close endings are the same up to the point that the close ending extends the melody, so there I have added only one red arrow indicating the extension of the melody in the close ending. As we see above, in punctus D the open and close have divergent endings rather than the close being an extended ending, so above I have added 2 red arrows to indicate divergent material in the 2 halves of the punctus.

One of the key features of any estampie is that there is no set number of measures in a section. A, B and C all had 7 measures before the endings; now D, E and F have 8.

Punctus E

In this section, my modern notation cannot have a repeat sign, as the melody is slightly different the second time in the 5th and 6th measures. In modern notation, I have therefore included the 1st and 2nd time bars to show the open and close, but reproduced the music in full, and highlighted the variation in a red box in the neumes and the modern notation.

This variation within a punctus is unique to this estampie, so it raises the obvious question: is this scribal error? We see from the neumes and notes inside the red boxes that the 3 notes in question are identical in pitch the first and second time, but the neume grouping and therefore the rhythm is different. Both times it makes musical sense, so this does not resolve the question of error. We see that the 2nd, 3rd and 4th notes of the punctus, when repeated after my vertical black arrow, are written differently by the scribe the second time but mean the same, so this raises the question of scribal consistency. The obvious errors in the rest of the piece (rubbings out and two missed half-puncta added at the end) make scribal error probable, but not certain. Since both times the notes in the red box make musical sense, it leaves open the question of which notes to correct if we assume error.

In my notation and performance, I decided to keep the variation in, on the basis that I prefer to edit as lightly as possible and assume scribal intentions are as written unless there is an inescapable error. (On the subject of modern over-editing, to the point of completely obscuring the original medieval music, see my comments on E. J. Dobson and F. Ll. Harrison’s now standard modern rendering of Mirie it is, under the heading, Deciphering the music.)

If this is a genuine and deliberately-written variation, a likely explanation is that it developed during performance and the scribe wished to keep it in. If so, it underlines the fact that notation is fixed and static, whereas performance is dynamic and develops over time. Any musician who has committed a piece of music to memory knows this, and if you are such a person you have probably had the same experience as I: we don’t perform the piece for a while, we return to it from memory and a phrase eludes recall; so we return to the written music, then discover we have unknowingly made now-established changes in performance over time – and sometimes prefer them to what we originally learned.

The idea that any piece of music ought to be performed exactly the same each time is predicated on the notion that music ought to be fixed and final, performed precisely as written. As I explore in the articles on Kalenda maya and the medieval performance style, this is an idea that can only persist where there is both written music and literate musicians, and is alien to a musical tradition that works by learning from performance or that values extempore additions, as is the case with both traditional and medieval music (as I argue in the articles).

Punctus F

As noted above, the scribe’s method was to write everything out instead of notating repeated sections once followed by distinct open and close endings. The scribe wrote the music for punctus F only once, realised his omission, then added the repeat of punctus F at the end of the music, as we see on the annotated manuscript page, indicated above by Fi and Fii.

We see the same issue in punctus F as in E – deliberate variation or scribal error? – shown above in the same way with red boxes. I opted for the same solution as in the previous section, keeping both versions.

Punctus G

There are 4 notable features of punctus G:

i. There are a lot of rubbings out and corrections in this section. Is this a scribe correcting a faulty memory; or in the process of working out a new musical idea; or an accident-prone scribe on a bad day?

ii. The music is written only once and …

iii. … does not have an open and close ending. To match the estampie form, based on the double versicle, and to conform to the rest of this piece, I have added a repeat in modern notation and performance.

iv. Punctus G is a simplified version of punctus F, missing out the 5th interval jumps. The only difference between the open and close in punctus F is the repeated rather than singular note f’. In punctus G, the final note is a maxima (double longa) rather than the 2 longas in F.

Punctus H

As with punctus G, section H has many rubbings out and corrections; the music is written only once and does not have an open and close ending, so I have added a repeat to match the estampie form.

Punctus I

Like punctus F, section I is split, but not because the scribe forgot to write it twice: what is clearly the first portion is added to the end of the music after the also misplaced and added second half of punctus F, and the two halves of punctus I make one unrepeated whole, indicated by the scribe marking a cross.

Like punctus F, section I is split, but not because the scribe forgot to write it twice: what is clearly the first portion is added to the end of the music after the also misplaced and added second half of punctus F, and the two halves of punctus I make one unrepeated whole, indicated by the scribe marking a cross.

As with puncta G and H, since the music for I is written once and does not have an open and close ending, I have added a repeat to match the estampie form.

Punctus J

Punctus J is in 2 sections, and leaves us with a question about how to end the piece.

The first part (above) is monophonic, as are all the previous puncta; whereas the second part (below) splits into 3 voices: the middle voice repeats the monophonic first part with a different ending; the top voice is a punctuated drone on f’’, an octave above the finalis; and the bottom voice turns the final portion of music into a gymel, a form of medieval music based on harmonising in thirds, found only in England and Scotland. (For more on the gymel, click here.)

It is not unknown for an additional voice to be added only at the end of a piece of music. For example, Lambeth Palace Library MS 457, c. 1200, includes 3 pieces of music for 2 voices (about which there is an article here). At the end of the third piece, Mater dei (Mother of God), a third voice is added for the final phrase only. (That music can be heard by clicking here.) In Mater dei the music repeats with new words, which means the third voice disappears on the da capo repeat and reappears again in the final phrase. Should the 2 additional voices at the end of the Douce 139 estampie likewise disappear and return by repeating punctus J from the beginning?

I judge the answer to be no: an examination of the monophonic first half of punctus J and the middle voice of the polyphonic second half shows that this is the same material repeated until the monophonic open ending and the polyphonic close ending. This is demonstrated below and shows that, like most other puncta, J is written out in full, with a polyphonic ending on the repeat.

Conclusion and remaining questions

Together with three tunes in British Library Harley 978, c. 1261–65, probably ductias, and three more estampies (one only a fragment) in the Robertsbridge Codex (British Library Additional 28500), c. 1320–1400, this English estampie is a cultural treasure: these tunes collectively comprise the small remnant of English medieval instrumental music to have survived.

As we have seen, the chief distinguishing feature of the estampie form was irregular section lengths. As Johannes de Grocheio put it, the stantipes or estampie “is determined by puncta since it is lacking in that percussive measure which is in the ductia, and is recognised only by the differences between its puncta.” Since the estampie format was not rigid and unyielding, we would expect variation within the genre, as described above with 4 types of estampie. We have seen this in practice in the Douce 139 instrumental, which is my estampie type iii: consecutive or linear with mixed open and closed endings, with a nod in the first three puncta to type iv, the compound estampie.

We have seen the following issues and inconsistencies with the writing of this untitled piece, all requiring interpretation:

• Open and close endings are clearly intended, but not marked as such in the music.

• However, 3 out of 10 puncta do not have open and close endings.

• Repeated sections of music are written out in full rather than written once with a repeat indicated, but the music for 3 puncta is not written twice.

• In 2 of the puncta, repeated music is written with a variation the second time: is this the scribe’s intention or scribal error?

• The whole piece is monophonic except for the polyphonic repeat in the otherwise monophonic final punctus.

Some questions remain.

• Was this the script of a composer working out musical ideas, changing his mind leading to notation erasure, with some of the open/close endings yet to be formulated? Or a musician with a failing memory, trying to remember quite how the piece went? Or a scribe on an off-day, making many notation mistakes and correcting most but not all of them?

• Does the lack of an open/close ending for some sections mean this was a musician sitting loosely to convention? Or one who didn’t fully understand it? Or one who couldn’t remember all the details of a remembered melody?

• Does the polyphonic ending indicate an instrument that can play three parts at once, a harp or a keyboard? Or separate instruments, an ensemble of three?

• Would three instruments play in unison and split at the end? Or one instrument play solo and two more join at the end? Or would polyphonic accompaniment be added extempore where the music is written monophonically, before the written polyphony at the end?

Since we have only one source and can make no comparative judgements, and have insufficient historical data about estampie performance, none of these questions have answers.

My own performance in the video which begins this article (also available by clicking here) is what I make of the manuscript, my own attempt to reconcile the problems. Whatever decisions we make to arrive at a musical compromise between imperfectly-written music and a convincing performance, the original material is so strong that, whatever decisions are made, I am convinced we will arrive at an exciting, engaging, melodically interesting and historically important piece of 13th century English music.

© Ian Pittaway. Not to be reproduced in any form without permission. All rights reserved.

What a wonderful post! It’s so lovely to find such deep thinking about medieval musical matters outside of the academic paper mill.

I’m wondering about the irregularity of the English piece you write about. It’s my understanding that the (late/r 14th c) Italian istampitta had irregularities similar to what you describe here, though the Italian examples are considerably more complex (ie. Chominciamento de Goia). I expect you would raise – and answer – a host of questions pertaining to potential sources of influence, or not (given the gap in time).

Your thoughts?

Thank you, Leslie. All the surviving French estampies from c. 1300 and Italian istampittas from c. 1400 can be read clearly from the page, and don’t have the host of interpretation problems this English piece has. They’re all complex in the sense that a punctum does not have a set length, which is indeed what indicates an estampie, but as you suggest there is something special about the Italian examples. The English estampies in the Robertsbridge Codex, c. 1370-1400, follow the straightforward French model, i.e. Ax/Ay, Bx/By, Cx/Cy, etc., whereas the Italian istampittas have a compound structure. For example, Ghaetta is ABCx/ABCy DECx/DECy FECx/FECy GBCx/GBCy. It’s important to notice that this isn’t peculiar to Italian istampittas – nearly all the pieces in the Italian source of c. 1400 have this compound structure, that is to say, the trotto and the four saltarelli have it, too. This seems to suggest that this extra complexity is about what was happening in the milieu of this Italian source, rather than in istampittas specifically, especially given the closeness in time to the estampies in the Robertsbridge Codex, which do not follow the compound model.

I think we can sure that the English estampie – if that’s what it is, as it appears to be – in the article above, late 13th to mid 14th century, follows the English/French model. Though its notation is problematic, it is at least clear that it doesn’t have the compound structure of the istampittas.

All the best.

Ian

Greetings again, Ian!

Have you considered thinking through the metrical questions using what is known about dance and “choreometrics”, as described by Joan Rimmer (for instance)?

Leslie

Hello, Leslie, and thank you for your question.

There are three problems with trying to work on a piece like this using notions of choreography. Firstly, there is no evidence that the estampie was a dance, as I state in the article above. Despite the fact that modern writers repeatedly call the estampie a dance, no medieval writer says so. Secondly, even if we did have a clear medieval statement that the estampie was danced to – and all the evidence points the other way – we know next to nothing about dance from the period of this piece, the late 13th to mid 14th century, beyond static images, with no notion of what came before or after the figure shown, or even what dance is being depicted much of the time. We know most about the carole, but even in this case some of the evidence is arguable, and we have no detailed choreography. Thirdly, the idea of metrics in dance and dance music, a recurring pattern of rhythmic beats, is rather antithetical to the estampie form, which is characterised by rhythmical variety and unequal lengths of puncta.

All the best.

Ian

Thanks very much for your reply, Ian!

I’m aware of the evidentiary issues and thin support for characterizing transmitted estampie as danced dances. To be honest, given the nature of the record (and the range of quite interesting accounts from outliers in the academic community), I’m not even sure that more of the transmitted troubador/trovere material might not have been both danced as well as sung, as well as serving as musical bases for courtly contrefacta.

I’m actually quite interested in moving “off” the texts, or rather, approaching the transmitted musical texts as evidence (at best) of a kind of oral process. Which means that their notated forms are provisional (at best). Which means that they might be just as susceptible of analysis through the (admittedly limited) evidence of actual dance (or what might be inferred or borrowed from ethnomusicology, or “chorometric” anthropology) as through the usual historiographic models. Something like historical musicology meets ethnomusicology.

I haven’t seen anyone respond to Joan Rimmer’s comments, and I wondered if you might have a few thoughts. Perhaps in the future ….

All the best,

Leslie

Hello, Leslie.

There is some clear evidence of medieval sung dances – the carole was one – and this may have included some of the Cantigas de Santa Maria, as I show in this article https://earlymusicmuse.com/performingmedievalmusic3of3/ under the heading ‘Musical function’. It’s certainly true that some of the borrowed troubadour tunes were originally dance music, but there is some serious doubt about whether they were sung dances as performed by troubadours, for reasons I explore under ‘Non-mensural music, free rhythm, and its implications’ in this article: https://earlymusicmuse.com/performingmedievalmusic3of3/

There’s plenty of evidence for an oral process at work in troubadour material (which I will present in articles that will appear here eventually, too long in the pipeline, alas), and the continuing process of the oral tradition is a clear factor in musical variation – see https://earlymusicmuse.com/kalendamaya/ and https://earlymusicmuse.com/angelusadvirginem/

I’m very sceptical of drawing on ethnomusicology for research into medieval music, if what you mean is the implicit model that suggests medieval music is old, people in location X have traditions unchanged for hundreds of years, therefore the two are linked. Firstly, we need evidence of an unchanging tradition, and in my reading that is usually assumed based on cultural stereotypes, then we need to show that there is a real link between what happened in location A 600 years ago and what is happening in location B in the present day, and I’ve never seen any evidence presented.

Joan Rimmer wrote a great deal, so I’d need a specific reference to give any thoughts.

All the best.

Ian

My partner is looking for an interpretation (ie not in tablature) of the pieces in the Robertsbridge Codex. He is working on the earliest known keyboard instrument, RCM1, the clavicytherium.

I have not been able to find any printed matter for sale nor reference – have you any suggestions? Presumably you, when you played the etampe had had the piece interpreted. Going to commercial sites on the web takes me down rabbit holes or round the mulberry bush (to mix one’s metaphors) but doesn’t get me the sheet music!

Any help would be much appreciated.

Hello, John and Grant.

The interpretation of the estampie in the video above is my own from the original neumes, and I explain the problems of interpretation in the article.

The Robertsbridge Codex keyboard pieces are numbers 42-44 in modern notation in Timothy McGee (1990) Medieval Instrumental Dances. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. It is for sale on the following pages:

https://www.abebooks.co.uk/servlet/SearchResults?sts=t&cm_sp=SearchF-_-home-_-Results&tn=Medieval%20Instrumental%20Dances

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Medieval-Instrumental-Dances-Music-Timothy/dp/0253333539

https://biblio.co.uk/medieval-instrumental-dances-by-mcgee-timothy-j/work/3413124

https://www.brownsbfs.co.uk/Product/McGee-Timothy-J/Medieval-Instrumental-Dances/9780253333537

https://www.whsmith.co.uk/products/medieval-instrumental-dances-music/timothy-j-mcgee/paperback/9780253333537.html

https://www.alibris.co.uk/Medieval-Instrumental-Dances-Timothy-J-McGee/book/39147030

https://wordery.com/medieval-instrumental-dances-timothy-j-mcgee-9780253333537

I hope you’ll post again with news of the clavicytherium.

All the best.

Ian

Thank you very much. I’ve passed it on to Grant and hopefully he will be able to make sense of it – he’s the organologist, I merely help.

Hi Ian ,

I am a student at the BRIT school, and I’m creating a sound design for Shakespeare’s ‘Richard II’ and I need to gather medieval music . Would it be ok for me to use your English estampie, 13th-14th century – citole interpretation.

If it is, would it be okay to ask for an MP3 or MP4 of it?

Hope you are well,

Many thanks,

Faye Knight

Hello, Faye.

I replied yesterday by email. If you haven’t seen it, please check your spam folder. If it’s not there, do let me know.

All the best.

Ian

Hello Ian: Great article, and a musically very satisfying and intuitive reconstruction that deserves to make the rounds of the traditional music crowd – I think it would become a favorite!

I’ve sent you a separate inquiry about a related musical inquiry. With regard to the discussion in the above comments, I was fascinated by the structure of the Italian estampie example “Ghaetta” that you cited. Do you have a recommended source for hearing those Italian estampies?

I’ve done a great deal of private work on notations for tune structure, derived on my practice working with traditional Irish and American fiddle tunes. If I rewrite the structure you listed:

ABCx/ABCy DECx/DECy FECx/FECy GBCx/GBCy

using my format, I get the following:

A B C D

A B C E

F G C D

F G C E

H G C D

H G C E

I B C D

I B C E

Viewed this way, we can see that the structure actually interleaves (in “acrostic” fashion) four different patterns:

AA FF HH II -> AA BB CC DD the “narrative” structure of chained couplets

DE DE DE DE -> the alternating trailing refrain lines (open/closed)

C C C C … -> a recurring medial “spine” that helps integrate the form

and the most interesting pattern of all…

BB GG GG BB – a chiasmus form ABBA

Perhaps the apparent complexity of the form arises from the interplay of these four interleaved patterns.

Are you aware of any theorists writing in source materials from the time that would have discussed these sorts of design patterns? Or modern academic (or non-academic!) writers investigating these structural devices?

All the best – Mark

Hello, Mark, and thank you for an interesting question.

I see exactly what you mean about the “chained couplets”, which of course is integral to the open and close endings. We have to be careful with the idea of the spine and the chiasmus, as every estampie is different, and there appear to have been national, regional or temporal differences. The spine is certainly there in all the Italian istampittas of c. 1400, but not in the English estampies or the French estampies of c. 1400. The chiasmus I remain to be convinced by. In other words, we can’t view either as integral to the estampie form per se, but the spine does appear to be part of the national (Italian) or temporal (c. 1400) variant of the form. I therefore don’t see any musical theoretical underpinning for your suggestion of interleaved patterns.

Later this year I’ll be publishing an article analysing all the French estampies together, each with a video.

I’ll reply to your other enquiry by email.

All the best.

Ian

Another great post! I’m glad you revisited this estampie and gave more clarifications regarding its structure and how it fits in with the others.

My first question is this: how do we know that the English estampie is meant to be interpreted as a single piece of music, rather than a collection of two or more short pieces? After all, I do not know of any other estampie with more than 8 puncta.

My second question is twofold and may be unanswerable without going into a long discussion. It is about general performance practice of the monophonic estampies. When interpreting the Italian istampittas and other instrumental works in Add MS 29987 I run into issues with musica ficta, and the general issues pertaining to monophonic music of the period. Firstly, can we assume that the leading tone should be raised at the end of pieces such as these (E.g., Trotto ends with a whole-tone F to G, which could be altered to F# to G)? This is done today in virtually all polyphonic music written after 1300 or so, but performers seem to make exceptions when playing monophonic music. Secondly, should we assume that these are meant to be interpreted polyphonically, with an improvised tenor, for example? Although most performances of these pieces seem to interpret them without accompaniment, or with only heterophonic accompaniment, the endings do not always seem to fit the musical style unless we assume there is an implied lower voice. For example, Tre Fontane ends on A, and I have yet to find a single piece of polyphonic music from the 14th century ending on that note, except in cases where there is a chordal root of D provided in another voice. A peculiar monophonic virelai by Guillaume de Machaut (V11 “He! dame de valour”) also ends on A. We do know that estampies could be played with multiple voices, thanks to Douce 139 and the Robertsbridge Codex, and I think the lack of independence of voices in these sources indicates that perhaps these polyphonic estampies are polyphonic expansions of originally monophonic estampies. I would love to hear your thoughts on this matter.

Many thanks!

Hello, Riley, and thank you for your comment.

The answer to your first question is easy. How do we know that the English estampie is meant to be interpreted as a single piece of music? Because that is how it is clearly written on the page, so this isn’t an interpretation, it’s just how it is. There’s nothing specific about 8 for the number of estampie sections. This unnamed estampie fits the rubric for the form: no fixed number of measures in a punctus, and no fixed number of puncta.

On the second question about most estampies being written monophonically, I’d make the following points.

i. The musica ficta of the Add MS 29987 istanpittas is clearly written on the page, and there’s a lot of it, so there is no need to add more that is not written.

ii. I hear a lot of performance of late medieval monophonic music where the 7th is habitually raised and it is clearly wrong, such as performers assuming a modern major key when the music is, for example, mixolydian.

iii. Ficta in monophonic and polyphonic music is not the same. In monophonic music, it is about the composer adding spice to the melody line. In monophonic music, therefore, the composer wrote what the player should play or the singer should sing. In polyphonic music, it is about smoothing the intervals between voices, as we know from writers such as James of Hesbaye, Speculum musicae, c. 1325. In Book II, Chapter 80, he noted that when two polyphonic voices sing notes moving to a unison, and the notes prior to the unison form a major third, singers prefer to alter the interval to a minor third: “And if two people sing at the same time, one la la la sol and the other la fa fa sol, does not the one descending to fa sing musica falsa? This singer would rather use not the major third but the minor third, because its voices more greatly please the ear.” The musica ficta changes to written polyphonic music were based on the principle of the closest approach from an unstable to a stable interval between two voices. In monophonic music, of course, this isn’t relevant.

iv. We don’t know how monophonic estampies were performed, but the existing polyphonic estampies suggest what type of second line may have been played. In the estampies of the Robertsbridge Codex, we have what looks very much like a tenor line. At the end of the Douce 139 estampie, we have a punctuated drone and gymel accompaniment.

v. I don’t think we can draw conclusions from the finalis of an estampie, as they don’t follow modal rules. They all seem to have their own rules, so I would need to be convinced that comparing the finalis of one with another is musically significant.

All the best.

Ian

Thanks for the thorough reply! I hadn’t thought about leading tones only being relevant in polyphonic music. I’m glad to know I can just play the istanpittas as written without the headache of trying to figure out what the unwritten fictas are.

Your point about the finalis of an estampie not following modal rules makes sense. I suppose the near contemporary music of Oswald von Wolkenstein confirms this, where he frequently uses a finalis of E in his monophonic works, while his polyphonic works fit more neatly under the typical modal framework (I.e., finalis of C, D, F, or G) of Guillaume de Machaut or Francesco da Firenze.

It is great to see historical discussion of musica ficta in Speculum Musicae. I haven’t had much luck finding free translations of medieval treatises, so getting to know the medieval perspective on musica ficta is a real treat.

Thanks again!

Hi Ian,

I am working on a podcast project for Sandwich Guildhall museum at the moment, and we need some medieval music for our intro. Could I make a recording of your estampie transcription?

All the best,

Katie

Hello, Katie.

Yes, of course. What instrument will you be playing on? When it’s done, I’d love to hear it.

Ian