the Virgin Mary and Jesus (c. 1260–80, made in Paris),

Talos (bronze giant in the Greek tale, Jason and the Argonauts)

and Venus (2nd century CE Roman copy of a Greek original).

In the Cantigas de Santa Maria, a collection of 420 songs in praise of the Virgin Mary by King Alfonso X and his court, 1257–83, there is a large group of songs featuring statues of Mary which talk, move, give protection, heal, and enact terrible acts of violence.

This article, the last in a series of six exploring the Cantigas, describes these surprising songs of sentient statues, placing them in the context of medieval beliefs about holy effigies and the long history of mythical moving images, including the goddess Venus, the adventures of Jason and the Argonauts, Pinocchio, and some current controversies.

We begin with a performance of Cantiga 42 on voice and vielle (medieval fiddle), in which a jealous Mary, inhabiting her statue, sends a man running terrified from his bed on his wedding night.

For this series of six articles on the Cantigas de Santa Maria, I read through the entire collection of 420 songs. I was, like most people interested in medieval music, familiar with its iconography of musicians at Alfonso’s court in 13th century Iberia, and I knew all the songs were in praise of the Virgin Mary, most of them versified accounts of miracles. Immersing myself in the Cantigas was a shock. The songs are fabulous and incredible, in the literal sense of based on fables, not credible, mythical, astonishing, and they inhabit an unfamiliar universe of supernatural events, deeply-ingrained chauvinism and casually-expressed violence. These abiding themes are explored in the previous Cantigas articles.

harps, gitterns, ouds and flutes.

(As with all pictures, click to see larger in a new window.)

The most ubiquitous element in the songs is statues of the Virgin, acting as conduits for the real presence of the Mother of God. The statues are always beautiful, powerful, and able to act at will. Mary’s image in wood or marble calms a storm (CSM 9); speaks (CSM 25, CSM 87 and CSM 303); her eyes are watchful and her arm moves (CSM 38); her fingers close around a ring (CSM 42); her breasts become real and give milk (CSM 46); she raises her wooden knee to receive an arrow to save a man’s life (CSM 51); she cries tears (CSM 59); her image protects a vineyard from hail (CSM 161), and causes the ships of her enemies to sink (CSM 264); her statue becomes angry, cries out and loses its colour (CSM 164); and so on. In each case, an image of Mary is animated supernaturally, behaving in ways that are recognisably human – moving, talking, expressing emotions – and recognisably divine – performing miracles to enact otherwise impossible power over people, objects and weather.

My aim in this article is to explore what these songs meant to Alfonso and his court in their own cultural milieu, to place these medieval miracle stories in their contemporary context and within the framework of stories of supernaturally animated images through history, from ancient Greece and Rome to the present day. With reference to the Cantigas, classical gods, Shakespeare, Pinocchio and present-day India and USA, we find that these medieval stories have more contemporary resonance and relevance than may at first appear.

Themes and meanings

In the Cantigas de Santa Maria, and indeed in medieval literature generally, there is no such thing as a random incident: every event has meaning, and carries a specific religious message. The type of stories in the Cantigas that involve images of the Virgin – large statues or portable icons – can be grouped into four categories or themes, presented here with representative examples.

(i) Healing

In CSM 324, Mary cured a deaf-mute man who had not spoken for two years, apparently as a reward for showing curiosity about her statue. He asked, with signs, what the statue was. Upon hearing the answer, “his tongue loosened and broke into speech, and he began to bless the Holy Virgin.”

In CSM 127, a mother was wounded and weeping because her son kicked her. She asked the Virgin to avenge her and consequently he suffered great pain. What follows appears to be the Virgin’s elaborate plan to make him suffer so he could be healed and forgiven. The son begged his mother’s forgiveness, and together they travelled on pilgrimage to the Virgin’s church at Puy in France. When they arrived at the church, a force (presumably Mary) prevented him from entering, though the people tried to drag him in. The priests, upon instructing him to make confession and hearing that he had already done so, told him to amputate his own foot. He did so and was then able to enter the church. His upset mother prostrated herself in front of the Virgin’s statue at the altar, pleading for her son. Distraught, she fell asleep and dreamed that the statue of Mary spoke, telling her to place her son’s severed foot on his stump, stroking it in the Virgin’s name. This she did and his foot was restored.

(ii) The protective power of the Virgin’s image

is contemporaneous with the Cantigas and is

from Castile, one of the regions ruled by

Alfonso X, chief author of the Cantigas.

It shows Mary wearing the veil which, in

CSM 332, she used to put out the convent fire.

She is, as CSM 342 expresses it, “holding her

son, who took on flesh from her, in her arms”.

This is the kind of image which, in CSM 342,

miraculously appeared in marble and, in

CSM 136 and 294, inspired terrible revenge.

In CSM 9, a monk bound for Syria promised to bring an icon of Mary back to an innkeeper he was staying with in Damascus. He returned from Jerusalem with the best image of the Virgin he could find for her. On the road he encountered a lion and some murderous thieves but both times he escaped harm due to the power of the icon. Then, in a storm at sea, a voice told him to hold the image aloft to save the ship from sinking. When he returned to the lodgings, he was determined to keep the icon himself, and was pleased when the innkeeper did not recognise him. However, once in the inn’s chapel he was prevented from finding his way out. When he discovered the door, he confessed to the woman and gave her the image, placing it on the altar, whereupon the icon became flesh and flowed with oil.

In CSM 332, a nun lit a candle in a convent in Carrizo (in modern-day Spain), and the fire lit straw, which was there in abundance because of the cold weather. The flames spread rapidly to the altar, and Mary’s “statue instantly seized the veil from its head and threw it in front of the fire. After that, the fire did not burn a single thing. Instead, it was immediately put out at the bidding of her who has the elements in her power”. This story is a favourable contrast to CSM 39, in which lightning burned down a monastery, consuming everything except the statue of the Virgin: neither the threads of her veil nor the whiteness of her statue was affected, due to her holy power. The monastery, by contrast, was clearly of no account and could burn.

(iii) The Virgin’s ingrained image as a miraculous sign

CSM 188 takes the idea of being in someone’s heart quite literally: “a maiden who loved Holy Mary with all her heart” died and was cut open. “Inside her heart they found, I swear it is true, a likeness of the Glorious One, which she has graven there.”

In CSM 342, the Byzantium Emperor ordered that a church be built in Constantinople. Blocks of marble were brought in for the Virgin’s altar. “While they were sawing one of them, they saw her image inside, painted in colours, just as God had painted it … holding her son, who took on flesh from her, in her arms.”

(iv) The Virgin’s revenge

As an earlier Cantigas article explores, the Holy Mother of 13th century European miracle stories is a long way from the meek, mild and obedient Mary of modern Catholicism. Stories of statues of Mary involved in divine revenge are abundant. Revenge for insulting the Virgin is enacted either by the Virgin in a dream, or as a living presence, or on her behalf by Christ, a crowd or the king.

In CSM 59, statues of Mary and Jesus act together. An otherwise devoted nun decided to run away from the convent “with a gallant, handsome and valiant knight”. On the night she planned to leave, she knelt in front of a statue of Mary to say goodbye, whereupon “the mother of the saviour began to weep so that the sinner might repent.” Since this didn’t have the desired effect, as the woman arose, “the crucifix suddenly pulled his hand from the cross and, as a man of authority, struck her with force. He gave her a blow near the ear so hard that she bore the mark of the nail always … thus she lay motionless and senseless like one dead … neither God or his mother would allow it … The nuns … sang thanks to God for this miracle.”

Cantigas 136 and 294 tell different versions of the same story, with different melodies: in Italy, a German woman who was losing at dice was given a death sentence for throwing a stone at a statue of the Virgin. In CSM 136, the furious losing gambler “ran towards the child the statue held [the statue of Jesus held by Mary] and viciously threw a stone to wound the baby in the face. However, the mother quickly raised her arm, and the stone chipped a little hole in her elbow”. For this, the king ordered that she be “dragged through all the streets of the town”, i.e. bound and tied to a horse which dragged her behind while she was flogged until dead: “In this way did the mother of God wreak her vengeance.” In CSM 294, an angel statue moved its hand to deflect the stone the gambler threw at the Virgin’s statue, and onlookers “immediately seized the woman and threw her into the flaming fire.”

a stone at a statue of Mary and Jesus. The illustration gives details not present in the song:

the horseback executioner’s flail; the devil pulling the hair or riding on the hair of the

woman in the throes of being excruciatingly killed; the crowd pointing to the man at

the front, drawing the viewer’s eye, who in turn points to the woman being killed while

raising his other hand palm out, which signifies astonishment mixed with pain.

Few of the Marian miracle stories in the Cantigas are original to that collection. Rather, they were collected from earlier written and oral sources by Alfonso and versified by him into sung forms. He tells us this himself in the introduction to many of the songs, though always without being clear about his sources:

CSM 33: “I wish to relate to you a miracle which I found in a book and chose from among 300 accounts of miracles”

CSM 191: “according to what was told to me”

CSM 284: “as I found it written in a book and from among others had it copied and made a song from it”

One of the Cantigas on the theme of the statue’s revenge is particularly interesting since there is clear evidence of earlier sources, and it shows that Marian miracle stories were not necessarily Christian in origin.

Mary and Venus: the statue brides

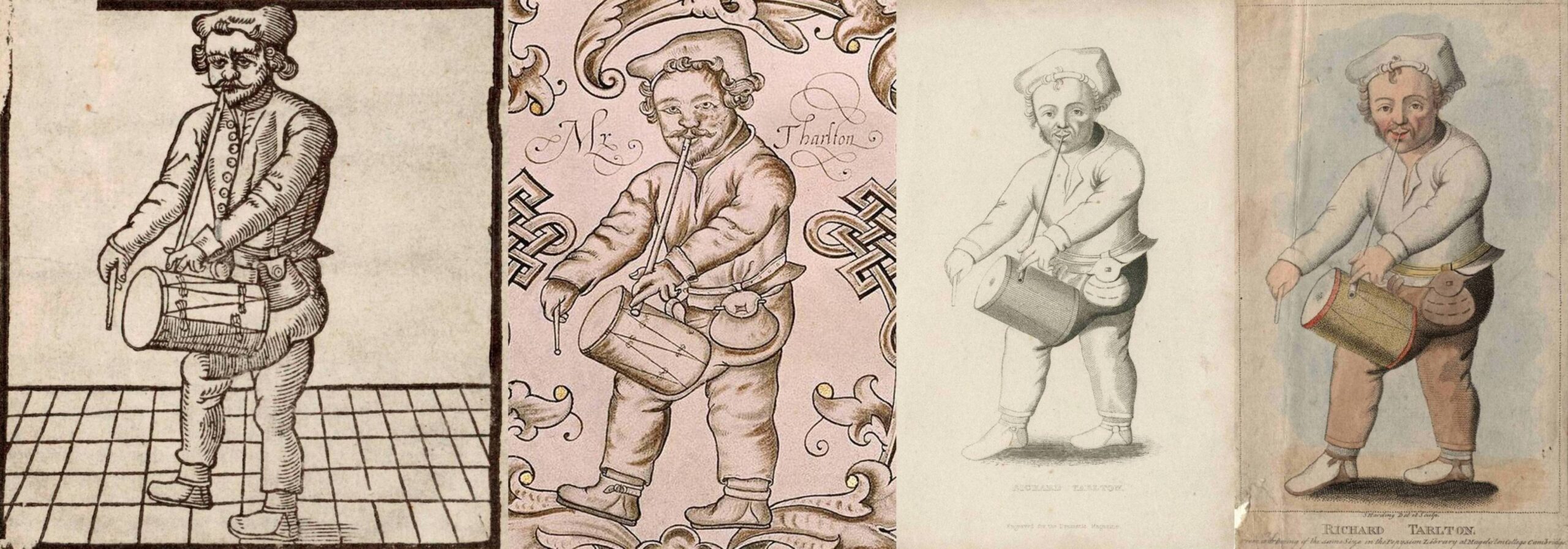

The idea of animated statues was not new in the 13th century, but was based on classical Greek and Roman models. Indeed, Cantiga 42 (performed on voice and vielle in the video above) has a story which is a direct adaptation of a Roman tale about the goddess Venus, changed to suit devotion to the Virgin.

The story as set out in Cantiga 42 is as follows.

A young man arrived with his friends at a park in Germany to play a bat and ball game. Before he played, he sought somewhere safe to place the ring given him by his beloved. He saw a statue of the Virgin placed under the portico of the town square while the church in which it usually stood was being renovated. As he placed his ring on the statue’s finger, he was struck by her beauty and declared that his betrothed now meant nothing, that he would now serve the Virgin, and that his ring was his pledge. As he knelt and then arose before the statue, he saw her hand close around the ring. He shouted, terrified, and a group came running to see. When they understood what had happened, they advised him to immediately join the monks at Clairvaux. This is significant: Saint Bernard of Clairvaux is credited with starting the cult of the Virgin Mary, and the Cistertian Order of France in Clairvaux was his.

The young man forgot his pledge to Mary and married his beloved. On his wedding night, he fell asleep and Mary appeared to him in a dream, shouting “Oh, my faithless liar!” She told him he must leave his wedding bed and his wife or she would make him suffer. He woke up but did not leave. He fell asleep again, and now saw Mary lying in the marriage bed, separating him and his new bride, angrily shouting, “Wicked, false, unfaithful one … why did you leave me and have no shame of it? If you wish my love, you will arise from here and come at once with me before daybreak.” He was so terrified that he left, wandered homeless for more than a month, entered a hermitage and served Mary, who then arranged for him to die so he could be with her forever.

Top left, friends play a ball game.

Right, one young man places his ring for safekeeping on a statue of Mary, pledging his love.

Bottom left, the jealous and vengeful Virgin haunts his dreams on his wedding night,

sending him fleeing in terror from his wedding bed.

Three details are striking about this account.

i. The statue is described as so beautiful that the young man immediately dismissed his beloved and their forthcoming marriage.

ii. The image is a living embodiment of Mary, a temporal stand-in for her eternal presence, its hand impossibly enfolding the ring as a living woman would.

iii. The Virgin’s jealousy is narcissistic (a theme further explored in the article, The Virgin’s vengeance and Regina’s rewards: the surprising character of Mary in the Cantigas de Santa Maria). Mary already has a husband in Joseph, is already Queen of Heaven, Mother of God, and the most important woman in the Christian universe. If a non-supernatural woman acted in the way this song describes, threatening vengeance if she does not receive total, eternal obedience after a fleeting encounter, then a healthy-minded person would not wish to serve her in fear the rest of their days, and would name her for what she is: a self-absorbed, dictatorial stalker. Essentially, CSM 42 is a Marian version of Fatal Attraction.

has a short affair with Alex Forrest (Glenn Close), bears a significant resemblance to

CSM 42, in which a betrothed man gives a ring to another woman – the Virgin Mary – with

promises of love. When he marries his original betrothed, the Virgin won’t let go, tracks him

down, appears in his nightmares, and sends him terrified from his wedding bed.

In Fatal Attraction, Alex likewise refuses to let go: “I’m not gonna be ignored, Dan.”

She stalks him and his family, with increasingly extreme attempts to wreak her

revenge on him and those he loves, as the Virgin Mary does in CSM 42.

There is an earlier story about Venus as a statue bride, upon which CSM 42 is based. The Venus story appears in the early 12th century work, De Gestis Regum Anglorum (On the Deeds of the Kings of the English), anglicised as The Chronicles or The History of the Kings of England, which covers the years 449 to 1127. The author of the anthology is Benedictine monk, William of Malmesbury. William relied on existing accounts, so the Venus story is earlier, but he gives no source and no earlier version survives. Though the story is set in Rome, it appears in a work on English kings without reason or explanation. Written down abound 150 years before the Cantigas, the Venus story is as follows.

A wealthy, young, noble-born, recently-married Roman liked to give frequent feasts. After one such event, he and his friends went to a field to play ball. To protect his wedding ring, he placed it on the finger of a bronze statue of Venus. After the game finished, he could not retrieve his ring since Venus’ finger had bent around it. He said nothing at the time, and returned to the statue that night with a servant, finding the finger straightened and the ring gone. He returned home and, as he got into bed, he felt something between him and his wife, “a kind of clouded sky, and dense, that it was able to be perceived, and it could not be seen”. He heard a voice, “Lie with me, whom you have married today. I am Venus, on whose finger you placed your ring, and I will not give it back.”

Some time passed, and during this period Venus prevented the young man from sharing any intimacy with his wife. Finally, because of his wife’s complaints, he related the events to his parents, who consulted Palumbus, a suburban priest and necromancer. Offered a reward for a positive outcome, Palumbus wrote a letter and gave it to the youth, saying, “Go to the crossroads at that hour of the night where they go to the quadruvium [medieval university], and stand silently and consider. A company of both sexes, of all ages and conditions, on foot and on horse, some merry and some sad, will pass by, but you must maintain silence. They will be followed by a man, rather tall in stature, stouter/fatter than the rest: give him the letter, and he will do what you wish.”

It happened just as the priest said. Among the procession was a woman, dressed like a whore, riding a mule, her hair loose, wrapped around her shoulder … The last in the procession was their demon chief. He gave the youth a terrible look and asked what he wanted. The young man remained silent and held out the letter. The demon did not dare disregard the familiar seal. He read the letter, lifted his hands to heaven and said. ‘Almighty God, how long will you suffer the wickedness of the priest, Palumbus?’ Without delay, he sent his followers to extort the ring from Venus and, eventually, she relinquished it. The young man thus regained the long-hindered love of his wife. However, Palumbus, when he heard the demon’s cry to God, knew that his life was nearly over, and soon after he died a miserable death, all of his limbs torn apart. William of Malmesbury adds to his uncredited source that Palumbus confessed unheard of atrocities before the Roman people.

In the middle of the 13th century, French Dominican friar, Vincent de Beauvais, gave a truncated account of the same tale in his Speculum Historiale (Mirror of History). Nearly all medieval accounts of the story are traceable to William of Malmesbury or Vincent de Beauvais, with attempts to date the event more or less precisely, because they were just as sure the Venus tale was an actual incident as Alfonso was sure the derivative Marianised version was true.

14th century fresco in the Church of

San Nicolò, Treviso, Italy.

By the time the story had been Marianised and transported to Germany in the Cantigas, a century and a half after William of Malmesbury, it had undergone several significant changes. The young married Roman was now a betrothed German; the statue of Venus had become the Virgin Mary; the supernatural “clouded sky” that prevented intimacy between husband and wife was replaced by the blocking body of Mary; and while Venus was unpleasant, jealous and obstructive, Mary was incandescent with threatening, vengeful, narcissistic rage. In the Marian version, gone altogether was the priestly necromancer and the mysterious other-worldly procession, led by a demon who had ultimate power over Venus and the necromancer’s mortal life: now Mary had ultimate power over the fate of the young man, in life and in death.

The details of William of Malmesbury’s story seem confused, as if it had been added to in ways that did not cohere with the original tale. The Roman goddess, Venus, symbol of love, beauty, sex and seduction, has been demoted and debased, having somehow become subject to the authority of the ghostly procession’s demonic leader, who can call on God to do his bidding. The suburban priest, Palumbus, appears to be both Christian and Satanic. Perhaps in William of Malmesbury we see a muddled Christianisation of an earlier story, associating Venus with evil forces to suit Christian theology, with other characters imported to drive home this point. The later Marian version in the Cantigas is neater and testament to the fact that, if a story is good enough to use for religious purposes, it really doesn’t matter if the religion is from a different time and place and the details don’t fit: that can be changed. The core elements remained: the ring as a symbol of marriage/betrothal, the supernatural statue imbued with the living human attributes of beauty, seduction, physical movement, malevolent emotions and jealous revenge, and the mortal man unknowingly drawn into a drama that threatens his most intimate relationship.

From Plato to Pinocchio: likeness comes to life

Not only does this story of the Virgin’s statue have a non-Christian antecedent, tales of living statues other than the Virgin Mary have historically existed in abundance.

The Greek epic poem, Argonautica, 3rd century BCE, tells of the dangerous voyage of Jason and the Argonauts to the remote kingdom of Colchis to retrieve the fleece of a winged ram with golden hair, symbol of authority and kingship. Along the way they battle hybrids and monsters, including Talos, a bronze colossus, created by Zeus (or, in some versions, created on Zeus’ orders) to protect Crete from invaders. Talos had life through his ichor, the fluid that is the blood of gods and immortals in Greek mythology. Talos’ ichor was a single vein of molten lead which ran through his bronze body, kept within by a bronze peg in his ankle. This bronze peg was his vulnerability and downfall, as many will remember from the 1963 film, Jason and the Argonauts.

In Plato’s account of Socrates’ dialogue with Meno, c. 402 BC, Socrates makes reference to statues created by Daedalus (father of Icarus), which were so realistic that “if they aren’t shackled, they escape – they scamper away. But if they’re shackled, they stay put … If you own an original Daedalus, unshackled, it’s not worth all that much … because it doesn’t stay put. But if you’ve got one that’s shackled, it’s very valuable.”

In Metamorphoses by the Roman poet, Ovid (43 BCE – 17/18 CE), the author includes the story of Pygmalion, who carved a woman from ivory so beautiful and realistic that he fell in love with his creation and lost interest in all human women. On the festival day of Aphrodite (Greek goddess of love, beauty, pleasure, and procreation, whose Roman counterpart is Venus), he wished for a human bride in the likeness of his carving. On returning home, he kissed the lips of his ivory woman to find them warm. He kissed her again, to find that she was becoming human. Aphrodite had granted his wish and they went on to have a daughter, Paphos.

in Nicolas Renouard, Les Metamorphoses d’Ovide Traduites en Prose Francoise,

et de nouveau soigneusement reveues, avec XV. Discours, 1651.

The detail of the young man so enchanted by the beautiful carving that he immediately fell in love with her and lost interest in all human women is repeated in CSM 42. It is a constant feature of Marian statues in the Cantigas that they are irresistibly beautiful to the faithful.

The stories of Ovid and other Roman and Greek writers continued to be retold and rewritten throughout the middle ages and the renaissance. Metamorphoses was hugely popular, being copied, printed and translated multiple times. William Caxton (c. 1422–c. 1491) was the first to translate it into English in 1480, and writers including Giovanni Boccaccio (1313–1375), Geoffrey Chaucer (c. 1343–1400), and William Shakespeare (1564–1616) used its stories.

Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale, 1611, has a mysterious final scene which echoes Pygmalion. Leontes, King of Sicilia, becomes paranoid about his beautiful and virtuous wife, Hermione, accusing her of being unfaithful. She suffers terribly because of her husband and eventually dies of a broken heart. In the final scene, a statue in honour of Hermione is revealed, which becomes living flesh and blood through Paulina’s working of a spell.

The Winter’s Tale, Act 5, Scene 3, lines 124–136:

and Rachael Sterling as Hermione’s statue,

in the 2016 Shakespeare’s Globe production

of The Winter’s Tale.

(As with all pictures, click to see larger

in a new window.)

PAULINA: Music, awake her! Strike!

[Music sounds.]

’Tis time. Descend. Be stone no more. Approach.

Strike all that look upon with marvel. Come,

I’ll fill your grave up. Stir, nay, come away.

Bequeath to death your numbness, for from him

Dear life redeems you.—You perceive she stirs.

[Hermione descends.]

Start not. Her actions shall be holy as

You hear my spell is lawful. Do not shun her

Until you see her die again, for then

You kill her double. Nay, present your hand.

When she was young, you wooed her; now in age

Is she become the suitor?

LEONTES: O, she’s warm!

A modern example of the theme is Pinocchio, the wooden boy made by the carpenter, Geppetto. Pinocchio is able to breathe, move and talk, since the wood he was carved from mysteriously had conscious life even before Geppetto began fashioning the block. Pinocchio, the work of Italian author, Carlo Collodi, first published in 1883, shows the wooden boy’s development from a child’s amorality to a developed morality through receiving the care of his creator, the long-suffering Geppetto. Pinocchio’s journey is filled with villains, tricksters, and the brutal violence that was normal in 19th century children’s literature. In the final pages, it becomes clear that Pinocchio’s trials and tribulations had been a series of moral tests: Pinocchio now understood Geppetto’s love and sacrifice, and repaid him by saving his life soon after Geppetto had saved his. Pinocchio learned that the fairy of the story was ill in hospital, and sent her his hard-earned money to pay for her treatment, which he had put aside for a suit. The fairy rewarded him by making him into a flesh and blood human, an element which is reminiscent of Pygmalion’s ivory statue, which required the supernatural wish-granting intervention of Aphrodite to make her human. It also echoes an occasional feature of the Mary icon stories in the Cantigas, in which part or whole of her image becomes living flesh through supernatural intervention.

The meaning of Mary’s animated images: “the one who sincerely believes finds power in a statue”

What is the Cantigas’ own understanding of Mary’s enlivened statues? Are they understood on the same or similar basis as the classical examples given: either like Talos, unliving material given life by the gods; or like Daedalus’ carvings, so lifelike that they live; or like Pygmalion’s ivory, Shakespeare’s Hermione and Geppetto’s Pinocchio, granted flesh and blood humanity by the gift of an external supernatural agency?

CSM 297 is the key, as it succinctly explains the importance of all the animated statue Cantigas. The unsung introduction explains the thrust of the song: “How Holy Mary showed her power through her statue, because a friar said that there was no power in carved wood.” The verses explain that “we must believe that God is complete power and that the saints receive it through him … And likewise, his great power is such that it can act through that thing which he deems worthy to be thus empowered. This is the true reason why the one who sincerely believes finds power in a statue. For just as living creatures receive power through hope, if only they believe, likewise the image receives it instantly from the saint it represents”.

Does the idea that an icon of Mary receives “power … instantly from the saint it represents” fit any of the other schemas? While most of these songs can be understood as an eternal living spirit animating temporal, non-sentient wood or marble, like the bronze giant Talos given life by Zeus, others clearly show Mary’s icons manifesting human biological substance, such as an icon becoming flesh (CSM 9), or having milk-expressing breasts (CSM 46), crying tears (CSM 59), or undergoing a change in complexion (CSM 164). The ‘living statue’ Cantigas as a whole do not seem to possess the internal logic of the Greek and Roman stories, but straddle disparate elements of pre-Christian stories.

From the early days of Christianity there was a belief that the bread and wine of the eucharist (the ceremony re-enacting the last supper) change their substance upon being blessed: they become the literal body and blood of Christ, without changing their qualities as bread and wine. Catholics call this change transubstantiation, a word first used in the 11th century and widespread by the end of the 12th, though the idea is clearly attested in the 4th century. If, in the medieval Catholic mind, blessed bread can be both bread and flesh without contradiction, and blessed wine can be both wine and blood without contradiction, then Mary’s statue can be both wood and womanly flesh without contradiction. Even so, the Cantigas statue miracles still contravene even the internal logic of Catholic doctrine. The real presence of Christ in bread and wine changes the substance but not the appearance: in the stories of Mary’s statues, both substance and appearance are altered.

This inconsistency is further illustrated in CSM 154, in which Mary is both an incorporeal heavenly spirit and a physical woman of bone and blood. In the song, a gambler loses and, in his anger, he shoots his crossbow up at heaven, aiming to wound “either God or his mother with an arrow”. He does so, showing that Mary’s presence in heaven is solid and physical, since “the arrow came down all covered with blood and struck the gaming board … they saw fresh, warm blood and … they understood that … the arrow had brought blood from heaven”. This was Mary’s miracle, performed “to free us from doubt”, with the effect that “the gambler without delay repented of his sins and entered a strict religious order, trusting in Holy Mary, the solace of sinners.” The meaning is clear: Mary in heaven has a solid body of flesh and blood.

Above, the gambler is annoyed at losing so he fetches his crossbow to aim at heaven (right).

wounding God or his mother in revenge for losing.

The internal evidence of the Cantigas is that these illogical conflations of physical body and heaven on high, of sentient life in non-sentient statues, did not trouble King Alfonso X or his sources. The medieval mind (if one can speak in such broad and generalised terms) was systematic up to a point, but relied more on rigid authority than on logical investigation. It reminds me of the words of Revd. Colin Morris (1968): “In everyday speech this is like saying that something is wet only because it is dry, near only because it is far away, and relevant only because it is irrelevant … Ah, breathes the theologian. That is paradox and, therefore, profound … Ah, says the man in the pew, it’s beyond me but I’ll take the parson’s word that it means something … So what? says the man in the street … say that he [a theologian] is unintelligible and he will take it as a compliment”.

Reverence and relevance

Navarra (now an autonomous province in

modern-day Spain) is from the time and place

of those revered by Alfonso and his

subjects in the Cantigas.

The subject of this article may seem the stuff of idle intellectual curiosity, but that would be to miss an important link between the world of Alfonso’s Cantigas and events around the globe today.

As we see in the Cantigas, statues that reputedly weep and move symbolise far more than a claim to the existence of the supernatural, and they inspire something far more potentially deadly than a polite debate between religious faith and rational thinking. The reverence given icons and statues is as potent and relevant now as in the 13th century of the Cantigas. Images not only represent the person being revered, they encapsulate the identity of a whole people, an ideology, an ‘us’ that is different to and opposed to ‘them’.

This is made clear in CSM 324, which describes an event in Seville that happened “because of a very beautiful statue of the Holy Virgin Mary that the king had brought there.” The statue is of “this glorious Virgin, who freed us from the great evil the devil did to us and placed us in the grace of her son, Jesus, who chose to become God and man.” When the congregation in the cathedral asked to see the statue in King Alfonso’s possession, they were not simply requesting a viewing of an interesting object, they desired to see a representation of that which defined them, which represented their truth, the meaning of life, their faith in eternal salvation which delineated them as ‘us’, the believers, apart from ‘them’, the wicked who do not believe, the latter characterised in the Cantigas as Moors, Jews and heretics (see the fifth article in this series).

For some, this division of the world into the faithful and the enemy, encapsulated in a statue, has barely changed. Indian author and public speaker Sanal Edamaruku, President of the Indian Rationalist Association, appeared on live television in March 2012 to investigate a statue of Christ on the cross in the Church of Our Lady of Velankanni, Mumbai. The water dripping from its feet had been perceived by the faithful as a miracle, attracting large numbers of devotees who collected the apparently holy water in bottles, some drinking it in the hope of curing illness. Sanal soon found the explanation: the water dripping from Christ’s feet was from an overflowing drain, pulled into the wall and onto the statue through capillary action. On live television, Sanal explained what he found: “This was sewage water seeping through a wall due to faulty plumbing. It posed a health risk to people who were fooled into believing it was a miracle.” He accused the church of manufacturing miracles to make money. Bishop Agnelo Gracias and others said they had never claimed the water was miraculous. It was special pleading: neither had they investigated the source of the water nor dissuaded the faithful from their beliefs. The church demanded an apology from Sanal, threatening him with legal action. He said he would debate with them in court. The issue soon escalated. Offended Christians went to police stations to press charges under the Indian Penal Code, section 259a, dealing with “deliberate and malicious acts, intended to outrage religious feelings”, i.e. blasphemy. In cases of blasphemy, the police could arrest without a duty to investigate until the trial, potentially many years away. Though the wording of the law did not fit the facts of the case – Sanal was not “malicious” nor did he intend “to outrage religious feelings” – he considered his liberty and possibly his life to be in danger when the Mumbai police refused to issue anticipatory bail, i.e. they denied him the possibility of bail if arrested and jailed. He left early for a speaking tour in Finland – and stayed there.

The message about faith, centred here on beliefs about statues and their supernatural powers, is the same as in the Cantigas : you must believe as we do; you are not allowed to dissent and, if you do, we will punish you with great force.

Sanal Edamaruku’s friend, Narendra Dabholkar, had campaigned for two decades for a legal anti-superstition bill, with punishments for self-styled holy men who claim to perform miracles, and the outlawing of rituals which supposedly ensure a pregnant woman gives birth to a son, the prohibition of human sacrifice in the name of religion, and of torture on the pretext of driving out evil spirits. It has yet to be written into law. For his campaign to bring the bill, Dabholkar received assaults and death threats. In August 2013, he suggested Sanal leave Finland and come to Mumbai, where he would protect him. Four days after his offer, Narendra was murdered by two unidentified gunmen at point blank range. Sanal remains in exile in Finland.

It is not only in the religious sphere that statues are given symbolic meaning and potency, expressing the ‘us’ we are meant to identify with, opposed to ‘them’, the enemy. Robert E. Lee was a commander of the US Confederate Army during the American Civil War (1861-65). The conflict was between the southern Confederate states, fighting to secede from the north so as to keep slaves and slavery, and the northern Unionists, fighting to unite all the states and ban slavery. A monument to Robert E. Lee was unveiled in 1924 in Charlottesville, Virginia. The event was a Confederate reunion, and the statue’s unveiling was performed by General Lee’s three year old great granddaughter, pulling off the huge Confederate flag that covered it.

In the intervening years, voices grew against the public monument to Robert E. Lee. A local official suggested in 2012 that the statue be removed. There was a pro-statue backlash. The calls for its removal grew louder. In August 2017, the planned removal of the statue led to a weekend of violence led by supporters of the statue with torches, shields and banners, with counter-demonstrators opposing them. One of the pro-statue protesters, James Alex Fields Jr., a self-proclaimed white supremacist, drove a car into a crowd, injuring 19 and murdering 32 year old Heather Heyer.

Remember: this was over a statue. When a statue (or a flag, a party, a country, a race, a religion) serves as a representation of communal identity, the individual merges with the group. Those who oppose the statue see themselves, as a group, threatened or disrespected by the existence of the statue. Those who see their own identity represented by the statue sees themselves threatened or disrespected by the possible or actual removal of the image.

Thus it is that, in the Cantigas, dissent is disallowed, and statues are often the locus of conflict. Moors, Jews and heretics are regularly depicted in the Cantigas disrespecting the image of Mary or Jesus, desecrating it or trying, without success, to destroy it. This serves to underline the idea that Moors and Jews are ‘them’, typically either killed or converted by the end of the song. Those who do not show appropriate respect and reverence to representations of Mary in painted wood, wax or marble are severely punished. Depending on the perceived gravity of the crime, some are released from pain after serving their sentence, while others are killed. In CSM 293, “a minstrel skilled in mimicry” was tempted by the devil – the ultimate representation of opposition – to mimic “a very beautiful statue of the peerless Virgin, holding her son in her arms … this displeased Jesus Christ, and he caused his mouth and chin to twist right up beside his ear. His neck as well and his arm writhed so violently that he could not remain standing and fell down on the ground.” People around him picked him up and carried him, running to the church. The minstrel prayed to God/Christ, confessing his sins, saying the punishment was deserved, but no mercy was shown. The next day, during mass, the “Virgin Mary had mercy on him and straightened his face and arm at once and made him well again”. His lesson learned, he would be too fearful to act any more as ‘them’, only as ‘us’.

who “caused his mouth and chin to twist right up beside his ear. His neck as well and his arm

writhed so violently that he could not remain standing and fell down on the ground.”

The woman who threw the stone at the statue of Mary and child did not get off so lightly as the minstrel. Perceived as too beyond the pale to be redeemed, she was killed by being bound and dragged behind a horse until dead (CSM 136) or seized by a crowd and burnt alive (CSM 294). Those who kill in the present day over symbolic statues, the murderers of Narendra Dabholkar and Heather Heyer, are ideologically at one with the killers in the Cantigas: the statue is ‘us’, and those who disrespect it must die.

One thematic link has run through all six of these Cantigas articles. For those of us in the present who wish to perform medieval music, a bridge has to be built between the world of Alfonso and the world of the listening audience. On the subject of statues, that bridge is there in plain sight: the vengeful, blood-thirsty and punitive aspects of the Cantigas have an uncomfortable resonance with modern events. It follows that some kind of conclusion and resolution must be reached if this material is to be performed.

The Cantigas de Santa Maria: summary of themes and performance questions

There are several contexts for understanding the background and motivation behind Alfonso’s Cantigas. The first article explored the huge influence of troubadour fin’amor – refined or perfect love – on medieval music and poetry, and the Catholic Church’s response, which was to apply the language and imagery of women in troubadour songs to the Virgin Mary. The second article examined the profound influence of this movement on the Cantigas. In Prologue B, Alfonso declared, “I wish from this day forth to be her [the Virgin Mary’s] troubadour”. The character of Mary in Alfonso’s songs is discussed in the third article, within the context of the hierarchical nature of medieval society. The fourth article about pilgrimage has, as its backdrop, medieval belief in the supernatural and its role in sending authoritative messages from a higher world; and the fifth article about the depiction of Moors and Jews in the Cantigas illustrates the role of religion in justifying the fight for political supremacy.

This final article about sentient statues has combined, to some extent, all of the previous themes. Statues of Mary in the Cantigas are always described as irresistibly beautiful, a result of the Catholic Church’s response to descriptions of adored women in troubadour fin’amor. Implicit throughout this article has been the character of the Virgin Mary, wielding her divine power with narcissistic demands for exclusive attention, punishing anyone who crosses her or who gives her less than her entitlement of worship and supremacy. Stories of Marian icons are always about authoritative, supernatural messages from a higher world; and part of that message is the rigid categorisation of people into the faithful and the heretics, the saved and the damned, Moors and Jews being supreme examples of the latter in the Cantigas. What this article has added is an understanding that, despite all the Cantigas’ internal assertions of righteous, religious purity, this claim is a grandiose illusion: 13th century Catholicism was syncretistic, absorbing not only the secular sensuousness of fin’amor, but aspects of Greek and Roman mythology, repackaged as tales of the Virgin.

Researching the Cantigas brings a series of jolts to the modern reader. The songs are, by turns, entertaining, fascinating and deeply shocking. There is a clash of worlds between the songs and the performer: the songs are medieval, religious, fundamentalist, chauvinistic, and supernatural; the performer will be contemporary, possibly atheist, hopefully nuanced, and probably with a modern scientific outlook. It does no justice to the material to ignore or avoid this clash, and this collision, in my experience, is the creative dissonance which makes the songs come alive.

Engagement with and performance of the material raises some potentially difficult questions:

• What is my attitude to miracles as I sing them?

• When I sing of the punishment and death of unbelievers, what thoughts and feelings do I bring to that, and what do I wish to convey to an audience, knowing the song is celebrating violence?

• Do I sing any of the songs about Jews being murdered by the Virgin Mary, reflecting divisive and punitive 13th century attitudes?

• Are there some songs too beyond the pale to sing?

• Am I, in the way I introduce the song and perform it, inviting the audience back in time to suspend their modern judgement and morality, or are we listening together with a knowingly modern understanding?

• Perhaps the most fundamental performance question is about communication and intelligibility: do I sing in the original language, knowing it is most likely that no one will understand, or do I devise a modern English version of the words, reconstructing the original syllable count and rhyme scheme so the audience can comprehend?

To these questions there are not always easy or universally-applicable answers. My hope is that this series of six articles about the absorbing and disturbing Cantigas de Santa Maria will go some way, for the performer of medieval music, to promote an engagement with the questions.

~ ~ ~ 0 ~ ~ ~

Three articles follow about the performance of medieval music, intended as practical guides, using the Cantigas as an exemplar for musical arrangements in historically-informed styles:

- Performing medieval music. Part 1: Instrumentation

- Performing medieval music. Part 2: Turning monophony into polyphony

- Performing medieval music. Part 3: The medieval style

Translation credits

The translations of the Cantigas de Santa Maria in this article are by Kathleen Kulp-Hill – see bibliography. Since the syntax of different languages makes it impossible to create a meaningful line by line literal translation in English that rhymes in all the same places as Castilian, Kathleen Kulp-Hill’s translation is presented in her book in verses without retaining individual lines. This is replicated in the above article.

My role in creating English verses in the videos that accompany these articles was to recreate, as far as possible, the original syllable count and rhyme scheme. The versification in English of CSM 42 is © Ian Pittaway, and the musical arrangement is © Ian Pittaway and Kathryn Wheeler.

Bibliography

Baum, Paull Franklin (1919) The Young Man Betrothed to a Statue. In: Publications of the Modern Language Association of America, Vol. 34, No. 4 (1919), pp. 523-579. [Available online by clicking here.]

Beresford, Adam (2005) Plato: Protagoras and Meno. London: Penguin.

Bennett-Smith, Meredith (2012) Sanal Edamaruku, Indian Rationalist, Proves ‘Weeping Christ’ Miracle A Hoax, Now Faces Years In Jail. [Online – click here to go to website.]

Bromwich, Jonah Engel and Blinder, Alan (2017) What We Know About James Alex Fields, Driver Charged in Charlottesville Killing. [Online – click here to go to website.]

Chakraborty, Abhishek (2018) Delhi, Maharashtra Police On Alert After Statues Vandalised: Highlights. [Online – click here to go to website.]

Collodi, Carlo (1883) The Adventures of Pinocchio. [Online – click here to go to website.]

Dissanayake, Samanthi (2014) The Indian miracle-buster stuck in Finland. [Online – click here to go to website.]

Express Web Desk (2016) Narendra Dabholkar murder case: A timeline. [Online – click here to go to website.]

Fortin, Jacey (2017) The Statue at the Center of Charlottesville’s Storm. [Online – click here to go to website.]

Jackson, Deirdre E. (1997) Shields of Faith: Apotropaic Images of the Virgin in Alfonso X’s “Cantigas de Santa Maria”. In: RACAR: revue d’art canadienne / Canadian Art Review, Volume 24, Number 2, Breaking the Boundaries: Intercultural Perspectives in Medieval Art / Entamer les frontières : perspectives interculturelles dans l’art du Moyen-Age, pp. 38-46. [Available online by clicking here.]

Kulp-Hill, Kathleen (2000) Songs of Holy Mary of Alfonso X, The Wise. A translation of the Cantigas de Santa Maria. Tempe, Arizona: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies.

McDonald, Henry (2012) Jesus wept … oh, it’s bad plumbing. Indian rationalist targets ‘miracles’. [Online – click here to go to website.]

Morris, Colin (1968) Include me out! Confessions of an ecclesiastical coward. Peterborough: Epworth Press.

Pinocchio: Carlo Collodi. (2018) Children’s Literature Review. [Online – click here to go to website.]

Rao, Anshumanth (2017) The Dangers of Dissent – Sanal Edamaruku. [Online – click here to go to website.]

Sutton, Benjamin (2017) The Story Behind Charlottesville’s Robert E. Lee Monument. [Online – click here to go to website.]

Vojvoda, Rozana and Paranko, Rostyslav (undated) Gestures of the Hand. [Online – click here to go to website.]

© Ian Pittaway. Not to be reproduced in any form without permission. All rights reserved.