Richard Tarleton – fool, actor, playwright, poet, musician and legend – was the foremost stage clown of his age, celebrated in his own lifetime and well beyond. As an actor, he was a star of the stage when permanent theatre buildings were new, a fool or comedian of great physical and verbal wit, a serious player of affecting pathos, and a member of Queen Elizabeth I’s own acting company, The Queen’s Players. As a successful playwright, he wrote in the tradition of morality plays. As a poet and essayist, he wrote on the theme of natural disasters and divine displeasure. As a musician, he was a player of pipe and tabor and a creator of extempore comedy songs. As a legend, much-loved and much-missed after his sudden death, he was a byword for exemplary wit, his name used to sell literature for decades, his image still used and recognised two centuries later.

Richard Tarleton – fool, actor, playwright, poet, musician and legend – was the foremost stage clown of his age, celebrated in his own lifetime and well beyond. As an actor, he was a star of the stage when permanent theatre buildings were new, a fool or comedian of great physical and verbal wit, a serious player of affecting pathos, and a member of Queen Elizabeth I’s own acting company, The Queen’s Players. As a successful playwright, he wrote in the tradition of morality plays. As a poet and essayist, he wrote on the theme of natural disasters and divine displeasure. As a musician, he was a player of pipe and tabor and a creator of extempore comedy songs. As a legend, much-loved and much-missed after his sudden death, he was a byword for exemplary wit, his name used to sell literature for decades, his image still used and recognised two centuries later.

This is the first of four articles trawling 16th and 17th century sources to build up a picture of the man. This introductory article begins with a short history of fools in their three types – natural, ungodly, and artificial – to put Tarleton in his historical context; clarifies what contemporaneous writers meant when they described him as a jester; then describes his ‘country fool’ clown’s costume and notable physical appearance. Two neglected topics comprise the second and third articles. Part 2: Tarleton the player and playwright considers his range as a comic and serious actor and his style as a playwight, with an evidenced reconstruction of his lost play, The Secound parte of the Seven Deadlie Sinns. Part 3: Richard Tarleton the musician and broadside writer examines his style as a taborer; describes Tarleton as a comedic creator of extempore songs from themes called out by the audience; and surveys the evidence for Tarleton as a composer of ballads. Part 4: Tributes to Tarleton – with a musical discovery from the 16th century summarises the broadside ballads, books and plays which praised Tarleton and used his persona after his premature death. In particular, a musical biography of Richard Tarleton, A pretie new ballad, intituled willie and peggie, has its words and music reunited after 400 years of separation in a featured video performance.

tarletones riserrectione: John Dowland’s musical tribute

tarletones riserrectione Jo: Dowlande from the handwritten Wickhambrook lute book, c. 1595,

played by Ian Pittaway on an orpharion by Paul Baker, with Ian’s divisions second time through.

Musical tributes top and tail this series of articles about Richard Tarleton, exemplary Elizabethan clown, beginning with the well-known instrumental by John Dowland, and ending with a new discovery, reuniting words and music separated for 400 years.

John Dowland (1563–1626) was England’s foremost lutenist and composer. He wrote for the solo lute; for 1 to 4 voices with lute, orpharion or viola da gamba accompaniment; and for viol consort with lute. He published 4 best-selling books of lute songs, the first book so popular it was printed 4 times in 13 years; and was internationally known for his composition, Lachrimae, much imitated by other composers. He was employed as a musician in the courts of King Christian IV of Denmark and King James I of England, and also worked in France, Germany, and Italy; he had patrons among the aristocracy, after whom many of his compositions are named (The Lady Russell’s Pavan; The Lady Rich’s Galliard; Sir John Smith, His Almain, etc.); and he translated Musice Active Micrologus, the treatise of German music theorist, Andreas Vogelsang, known as Ornithoparcus, for English readers.

Before the modern period’s ticketed events and recordings for sale, most musicians relied wholly on performance, teaching and, in some cases, printed publications for a sustainable income. The best way for a professional musician to be sure of a living was to have employers and patrons for whom music could be composed and played. It is significant, then, that tarletones riserrectione Jo: Dowlande, as it appears in the handwritten Wickhambrooke lute book, c. 1595, was a piece dedicated with no hope of financial reward, expressing Dowland’s own feelings. There may have been a personal connection, but there is no evidence the two men ever met. Both were public figures loved by others from afar, so Dowland was most likely an admirer, wishing to pay tribute to the much-loved musical comedian.

Finding the real Richard Tarleton

Who was the real Richard – or Dick – Tarleton – or Tarlton – and why was he so well-loved by John Dowland, and by the Elizabethan public generally? Separating the man from the myth takes some digging. The most detailed account of his route to fame, and now the most often cited, is dubious. A few of the stories of his verbal and physical wit in the posthumous jest books bearing his name are clearly genuine, but many repeat standard jest book material with Tarleton’s name inserted. Just one of his plays survives, but only in plot outline (reconstructed in the second article), and his surviving verse and prose (described in the third article) has been almost universally ignored in the modern day. He was remembered as a fine musician, but none of the music he played has previously been known to survive (newly investigated in the third article); and a surviving and well-attested broadside ballad written in posthumous tribute has been silent until now (words and music newly reunited in the fourth article). What emerges from the witnesses and evidence is incomplete, as any account of a life must be, but the real Dick Tarlton is far from being a shadowy or mysterious figure.

What follows in this first article is an investigation into the meanings of the terms used for Tarleton – fool, jester and clown; a clarification of what it meant to say Tarleton was a jester; the connection between fools and morris dancing; and a summary of the many accounts of Tarleton’s theatrical clown clothes, which he is seen wearing in the famous image of him playing pipe and tabor.

In these essays I use both spellings of his surname – Tarleton and Tarlton – according to the historical source.

Tarleton in context: a short history of fools

The fool or clown became a stock figure in Elizabethan theatre. Among those who played the part, there are more accounts of Tarlton’s fooling or clowning than for any other in that role. In the account of Tarlton in History of the worthies of England, 1662, Thomas Fuller discusses Tarleton’s choice of career.

His History of the worthies of England

was published posthumously in 1662.

“Many condemn his (vocation I cannot term it, for it is a coming without a calling) Imployment as unwarrantable. Such maintain, that it is better to be a Fool of God’s making, born so into the World, or a Fool of Man’s making jeered into it by general Derision, than a Fool of one’s own making, by his voluntary affecting thereof. Such say also, he had better continued in his Trade of Swine-keeping, which (though more painful, and less profitable) his conscience changed to loss, for a Jester’s place in the Court, who, of all men have the hardest account to make for every idle word that they abundantly utter.

Others alledge in excuse of their practises; That Princes in all Ages were allowed their fools, whose virtue consisted in speaking any thing without control: That Jesters often heal what Flatterers hurt, so that Princes, by them arrive at the notice of their Errors, seeing Jesters carry about with them an Act of Indemnity for whatsoever they say or do: That Princes, over-burdened with States-business, must have their Diversions; and that those words, are not censurable for absolutely idle, which lead to lawful delight.”

Some explanation is needed. There was a common understanding of three types of fool in the medieval and renaissance periods, as delineated here by Fuller: natural; ungodly; and artificial.

The natural fool – what Fuller calls “a Fool of God’s making, born so into the World” – was someone who, in today’s parlance, has a learning difficulty or developmental disability. English royalty were often patrons of natural fools, giving them a stable home at court and an allowance of fine livery. For example, Isabella, Queen of King Edward II, sheltered Michael in 1311–12, termed a fool in the royal accounts, given money described as alms rather than wages; Richard II kept two fools, both William, supplying them with large quantities of fine clothing during his reign in 1377–80; Henry VIII kept “Sexten the king’s fole”, also known as Patch, during his reign, 1509–47, paying three men to look after him, and he subsequently sheltered “William Somer, oure foole”; and Elizabeth I kept two natural fools during her reign of 1558–1603, Ippolyta the Tartarian and a Spaniard named Monarcho.

It shows the King playing a harp next to his natural fool, William Somer (also Somers or Sommers).

(As with all pictures, click to see larger in a new window.)

For the sovereign, this was more than an act of charity. In his work of 1511, In Praise of Folly, Desiderius Erasmus explains: “take notice of this no contemptible blessing which Nature has given fools, that they are the only plain, honest men and such as speak truth. And what is more commendable than truth? … For whatever a fool has in his heart, he both shows it in his looks and expresses it in his discourse; while the wise men’s are those two tongues … whereof the one speaks truth, the other what they judge most seasonable for the occasion. These are they that turn black into white, blow hot and cold with the same breath, and carry a far different meaning in their breast from what they feign with their tongue.” The natural fool, the innocent, was the person who did not understand the servile and self-serving fawning to which kings and queens were regularly subject: thus the monarch could be sure of hearing the truth from the innocent, who thereby provided an invaluable royal service. As Thomas Fuller stated in The Holy State and the Profane State, 1648: “It is unnatural to laugh at a natural”: the natural fool was not for merriment, but for rare candour.

The ungodly or immoral fool – Fuller’s “a Fool of Man’s making jeered into it by general Derision” – was someone who used their reasoning faculties unwisely to act against God’s laws or wishes. A broadside of 1569 (1570 in the modern calendar), The xxv. orders of Fooles, versifies 25 types of ungodly fools who “the carte of sin now-a-dayes doth drawe”, concluding, “God grant that all fooles wisedome may learne, And that they may good from yll alway discerne … God grante that on all partes we may now begin To repent of our follye, and flye from our sin.” Such people were the subjects of a subgenre of medieval and renaissance moral poetry which imagined ungodly fools of various types sailing together in a ship. This included Jacquemart Giélée’s Renart le Nouvel (Renart the New), France, 1288; Heinrich Teichner’s Das schif der flust (The ship of the river), Austria, c. 1360; and Jacob van Oestvoren’s Die blawwe schute (The blue boat), the Netherlands, 1413. The idea was developed most famously in Sebastian Brant’s Narrenschiff (Ship of Fools), Germany, 1494, which versified ungodly foolishness in various categories, including the vain, the gluttonous, those who get rich by robbing the poor, the hypocritical, the arrogant, adulterers, the complacent, the envious, astrologers, blasphemers, the gullible, deceivers, and slanderers.

by a woodcut. As we see from the cover, fools were visually signified by a hood with

stylised asses’ ears tipped with bells. The significance of this clothing is explored below.

The third category, the artificial fool – Fuller’s “a Fool of one’s own making, by his voluntary affecting thereof” – was a professional fool, a clown or comedian like Dick Tarleton. The artificial or “voluntary affecting” fool, when employed in royal service, is now popularly known as a jester and shown with the fool’s cap or hood, with two stylised asses’ ears tipped with bells, sometimes with the addition of a central protrusion representing a cockerel’s comb or coxcomb, dressed in pied colours, and often with a fool’s club, bauble/bladder on a stick, or marotte (stick topped with a miniature fool’s head). Dick Tarleton was described as, in Fuller’s words, “the most famous Jester to Queen Elizabeth.” We might expect Tarleton, then, to have worn the pied jester’s outfit with the ass-eared hood so familiar in modern images, but modern assumptions about jesters are misleading.

The earliest surviving records of entertainers in the European courts are from the 8th and 9th centuries. They were termed scurrae, meaning professional buffoons, and joculatores, literally jokers. The term joculatores developed into the more general jongleurs, meaning itinerant entertainers who performed juggling, acrobatics, music, and recitation. Before the 16th century, a gestour (spelt variously) was an entertainer who delivered gestes, stories, either in the form of songs or as narrative jokes. It is almost certainly in this sense that Alexander Mason, who served Edward IV, Richard III and Henry VII in succession in the 15th century, was described as both a geyster, a singer of stories, and a minstrel, literally little servant, by then meaning musical servant. It wasn’t until the reign of Henry VIII in the 16th century that jester took on the now commonly-understood meaning of a professional artificial fool.

The instantly recognisable ass-eared hoods did not appear until the 14th century and were not associated with professional fools, but with amateur societies. The outfit had its origin in the Feast of Fools, a festival which began in the Christmas season during the 11th century to enact the Magnificat of Luke’s Gospel (1: 46–55), in which the Virgin Mary says God “has brought down the powerful from their thrones and lifted up the lowly” through the birth of Jesus. For the Christmas season, high-ranking clergy changed places with junior clergy, and a fool bishop or boy bishop was elected to preside over worship until the Feast of the Circumcision on the 1st of January. In 14th century France, Germany and the Low Countries, this Feast of Fools gave rise to the amateur Sociétés Joyeuses (Happy Societies) who, at Christmastime, took part in fools’ plays and processions. It was these societies, which flourished into the 17th century, who introduced fools’ hoods with stylised asses’ ears, tipped with bells, as we see below.

We see this fools’ clothing internationally in psalters of the 14th and 15th century. This might lead us to believe that artificial fools everywhere wore fools’ hoods with asses’ ears, coxcombs and bells, and carried fools’ clubs, baubles, bladders or marottes. This wasn’t the case, as we know from English court records of livery ordered for both artificial and natural fools in the medieval and renaissance periods, which make no mention of this paraphernalia. Since artificial fools outside of France, Germany and the Low Countries did not, in reality, dress this way, why were they represented so in English psalters and in the decorative carvings of English churches?

in Henry VIII’s Psalter, c. 1540.

There were two reasons. (i) Such costumes were worn in France, and the art of English psalters – and church decoration, too, when it came to fools – was influenced by the Parisian school of manuscript illumination. (ii) Iconographical conventions require recognisable representations. The most typical illustration of a fool in a psalter was in the illumination for Psalm 53, which says, “The fool says in his heart, ‘There is no God.’” The psalm is clearly referring to an ungodly or immoral fool, which cannot easily be shown visually, so the effortlessly recognisable ass-eared hood and accoutrements of the French artificial fool act as a stand-in. In exactly the same way, the narrative in Sebastian Brant’s Ship of Fools describes ungodly fools, but the woodcut illustrations indicate this with the costumes of artificial fools (as seen above). In Henry VIII’s Psalter, c. 1540, an image of the King’s natural fool, William Somer, acts similarly as a visually familiar substitution for the ungodly fool of the psalm (rather cruelly, we might think). Further details in this image (above) serve to show the visual symbolism inherent in medieval and renaissance art. Neither a costumed French artificial fool nor William Somer the natural fool was the ungodly fool indicated in Psalm 53, but visual signifiers pointing to the intended meaning. In a similarly symbolic way, Henry VIII is shown playing the harp, indicating a divinely-chosen king in the mould of the biblical King David, typically represented as a harpist. Furthermore, the English king is shown with a clarsach, the Irish wire-strung harp, showing that he was Lord of Ireland, that he owned the clarsach supposedly possessed by the 10th century Irish chieftain and harpist Brian Boru (which he returned to Ireland in 1543) and was, from 1541, King of Ireland.

Right: An artifical fool for Psalm 53 in British Library Harley 1892, c. 1475–c. 1525.

Illuminations in other psalters give variations on the theme of fool symbolism. Above left is the illuminated initial for Psalm 53 from The Queen Mary Psalter (BL Royal MS 2 B VII, f. 150v), England, 1310–1320. The king looks at the fool and points heavenward, indicating the words of the pslam, “The fool says in his heart, ‘There is no God.’” The man he views is partially undressed, without hose or shoes, holding a bladder on a stick with his left hand, a familiar visual representation of a natural fool: the word for fool in medieval Latin was follis, originally meaning a leather sack or bag filled with air. In his right hand, the fool holds a large, round piece of bread, illustrating further lines from the psalm, “Do all these evildoers know nothing? They devour my people as though eating bread”. Above right is the same psalm from BL Harley 1892, a psalter produced in four sections between c. 1475 and c. 1525 (this image is from the second section, f. 68r), made in France and England or the Netherlands. The king points to the main subject of the image, showing the viewer that this is the ungodly fool – illustrated as an artificial fool this time – who says there is no God, who devours God’s people as though eating bread.

The ass-eared, bell-costumed fool, originating in the Sociétés Joyeuses, was recognised and used internationally as an instantly recognisable visual emblem, a symbol pointing to the meaning beyond it, but outside of the Sociétés Joyeuses of France, Germany and the Low Countries, it bore no relationship to the clothes worn by actual natural, ungodly, or artificial fools, with one exception: the stylised and costumed artificial fool of morris dancing.

The fool of the morris dance

English morris dancing, originally Morys, moreys, or morisse daunce, began as courtly entertainment in the mid-15th century, known in Flanders as mooriske danse, in Germany as Moriskentanz, in France as morisques, in Croatia as moreška, and in Italy and Spain as moresco, moresca or morisca. This originally high status display dance was performed in English parishes by the mid 17th century. Early accounts of morris make clear that it gets its name from Moorish dancing, as we see illustrated below.

The illustration above is from an edition produced in 1463 of Speculum historiale (The Mirror of History) by 13th century Parisian Dominican friar, Vincent of Beauvais (BnF Fr. 51, f. 171r). It shows two scenes from the life of Saint Josaphat, and it is the scene in the foreground which concerns us. No musician is shown, but we clearly see four male morris dancers dancing around a woman, variously called the Queen of May, judge, or goddess of luck.

The illustration above is from an edition produced in 1463 of Speculum historiale (The Mirror of History) by 13th century Parisian Dominican friar, Vincent of Beauvais (BnF Fr. 51, f. 171r). It shows two scenes from the life of Saint Josaphat, and it is the scene in the foreground which concerns us. No musician is shown, but we clearly see four male morris dancers dancing around a woman, variously called the Queen of May, judge, or goddess of luck.

The plot of the early morris dance was the wooing of the maid by the other dancers, who made exaggerated and extravagant movements to impress her. The winning dancer – the fool – was presented with an apple or golden ring as a love token by the maid. The fool has his stylised hood and marotte. All wear bells on their calves and ankles, and all have bells on their wrists except for the fool, who instead has them on the tails and elbows of his doublet. The dancer on the left carries a characteristically eastern scimitar, a visual indication of Moorishness, and the imitations of tall sikke or kyula hats of camel wool, worn on turbans, also indicates that the dancers are emulating Muslims or, in the parlance of the time, Moors: Moorish dancers = morris dancers. (At this time, tall conical head-dresses were popular in the west, too, but worn only by women, and made of cloth stretched over card or wire, as we see below.)

We see the same type of morris dance above with exaggerated movements, a fool, a maid and two male Moors in a manuscript of Augustine’s City of God, produced c. 1475 and 1478-1480 in Paris (The Hague, MMW, 10 A 11, f. 48v). The clothing is very similar to that seen above in Speculum historiale, 1463, and again the musician is out of the frame.

In the images of morris dancing above and below, by German engraver, printmaker and goldsmith, Israhel van Meckenem (c. 1445–1503), we see the same wooing story played out again by the dancers in a range of characters, including the fool in his distinctive clothes. Above, in Moriskentanz, c. 1475, we see the fool facing the Queen of May with his ass ears, coxcomb and marotte. Below, in Dance of the Lovers, c. 1490, we see the fool with his three visual indicators – marotte, pied clothes, and tongue out – and dancers in the character costumes of the rich and rural poor. In both these images, the visual imitations of Moorishness are now absent, and in both depictions we see the musician playing the universal instrument of the morris: pipe and tabor. With this instrument, we are now almost full circle in returning to the artificial fool, Richard Tarleton.

(As with all pictures, click to see larger in a new window.)

In Beverley Minster, a church in the East Riding of Yorkshire, there is a set of 68 choir stalls with magnificent misericords carved in 1520. Misericords – mercy seats – are shelves on the underside of choir stall seats. When the seats are upright, clergy rest their buttocks on the shelf, enabling them to remain standing during long services. Misericords were not simply functional, but crafted works of art, depicting everyday, fantastical, moral, didactic and symbolic scenes. On the seat above we see five ass-eared morris fools. In the centre, the left dancer is on the ground, and the dancer on the right is carrying a scimitar behind his head (hidden from view in this photograph), indicating Moorish or morris dancing. The central dancer has the asses’ ears on his hood in common with the other four figures, with an additional representation of the cockerel’s crest, the cock’s comb or coxcomb, a visual emblem meaning ‘I strut about like a cock: vain, conceited, a fool’. In William Shakespeare’s Henry V, Fluellen describes all the meanings present in a fool’s cap in less than one sentence: “an ass, and a fool, and a prating coxcomb” (Act 4, Scene 1). The fool circled on the left is carrying what appears to be a bell on a stick rather than the usual inflated bladder on a stick, and the fool circled right (detail above) is playing a pipe and tabor, the universal morris dancing instrument. The one image we have of Tarleton, replicated many times, has him playing pipe and tabor, as we will see below.

In the 15th century, the pipe and tabor became associated with the new courtly entertainment of morris dancing and therefore with artificial fools. The opening lines of Act 3, Scene 1, in Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, 1602, confirm the ongoing connection between the fool and the pipe and tabor:

Enter Viola, and Clown with a tabor.

Viola: Save thee, friend, and thy music! Dost thou live by thy tabor?

Feste: No, sir, I live by the church.

Shakespeare’s clown or artificial fool, William Kemp (or Kempe), was a morris dancer, famous for dancing the morris all the way from London to Norwich in his nine daies wonder accompanied by his taborer, Thomas Slye, as we see from the woodcut on the cover of his publication (below) telling of his feat. Richard Tarleton was both an artifical fool and a taborer (pipe and tabor player). The topical connections are clear: morris dancers had an artificial fool and danced to a pipe and tabor; fools were associated with taboring; Kemp the artificial fool danced the morris to a pipe and tabor; Tarleton the artifical fool played pipe and tabor. With such overlapping themes, it is reasonable to consider whether Richard Tarleton was a taborer for morris dancers. This is certainly possible and circumstantially credible, but overt historical testimony is lacking.

(23 days if you count the days off!), performed, written about and published in 1600, for

which the Mayor of Norwich gave Kemp a forty shilling a year pension for the rest of his life.

Tarleton the jester

For Tarlton’s origins and rise to fame, we return to Thomas Fuller’s History of the worthies of England, 1662, which has an entry for a jester in the court of Queen Elizabeth named Thomas Tarlton. That Fuller made the basic error of getting Richard’s first name wrong should alert us to the possibility that this may not be an accurate account.

“THOMAS TARLTON. My intelligence of the certainty of his birth-place, coming too late, (confessed by the marginal mark), I fix him here, who indeed was born at Condover in the neighbouring County of Shrop-shire, where still some of his Name and Relations remain. Here he was in the field keeping his Father’s Swine, when a Servant of Robert Earl of Leicester (passing this way to his Lords Lands in his Barony of Denbighe) was so highly pleased with his happy unhappy answers, that he brought him to Court, where he became the most famous Jester to Queen Elizabeth.

Our Tarlton was master of his Faculty. When Queen Elizabeth was serious (I dare not say sullen) and out of good humour, he could un-dumpish her at his pleasure. Her highest Favourites would, in some cases, go to Tarlton before they would go to the Queen, and he was their Usher to preface their advantageous access unto Her. In a word, He told the Queen more of her faults than most of her Chaplains, and cured her Melancholy better than all her Physicians. Much of his merriment lay in his looks and actions … Indeed, the self-same words, spoken by another, would hardly move a merry man to smile; which, uttered by him, would force a sad soul to laughter. This is to be reported to his praise, that his Jests never were profane, scurrilous, nor satyrical; neither trespassing on Piety, Modesty, or Charity.”

It is an engaging description of Tarlton’s origins and skills and it is therefore tempting to view it as a firsthand account. However, both aspects, the origin story and his relationship with the Queen and her courtiers, are dubious. As well as the discrepancy in Tarlton’s name, we must take into account that Fuller had no first hand knowledge – Fuller was born in 1608, 20 years after Tarlton died, and he wrote 50 years after Tarlton’s death – whereas the actor and playwright Robert Wilson worked alongside Tarlton, and he gives an altogether different account.

Right: Elizabeth’s principal secretary, Sir Francis Walsingham, painted 1585.

In 1583, the principal secretary to Queen Elizabeth, Sir Francis Walsingham, formed her royal acting company. Walsingham recruited Tarlton from The Earl of Sussex’s Men, so he was already an actor when he became a royal appointee: he was not therefore “in the field keeping his Father’s Swine,” nor discovered by “a Servant of Robert Earl of Leicester” and taken to the royal court. The Queen’s Players (also called The Queen’s Men, Queen Elizabeth’s Men, or The Queen’s Majesty’s Players) also included several former members of Leicester’s Men, including Robert Wilson. Robert Wilson’s play, the three Lordes and three Ladies of London, was published in 1590, only 2 years after Tarlton’s death. In it, the character Simplicity describes Wilson’s colleague Tarlton as “a prentice in his youth of this honorable city [London], God be with him: when he was yoong he was leaning to the trade that my wife vseth nowe, and I haue vsed, vide lice shirt [videlicet – viz. – namely], water-bearing”. Wilson knew Tarlton personally; used his correct name; stated that he came from London, not Condover in Shropshire; and that he was originally a water-bearer, not a pig farmer. An attempt to combine the two accounts soon runs into trouble. It is inconceivable that Tarlton was discovered on his father’s supposed Shropshire pig farm by “a Servant of Robert Earl of Leicester”, taken to be Queen Elizabeth’s jester, then became a water-bearer, then an actor in The Earl of Sussex’s Men before being recruited back into the Queen’s service: it can only be that Wilson is correct and Fuller in error. That Tarlton was a water-carrying labourer before being a comic actor tells us that he was certainly not from a wealthy family, and that he had physical stamina. This working class origin confirms the anonymous book, Tarltons Newes out of purgatorie, 1600, which states “he was only superficially seene in learning, having no more than but a bare insight into the Latin tung, yet he had such a prompt wit”.

Tarlton, along with the other Queen’s Players, was appointed as an Ordinary Groom of the Queen’s Chamber, a title which carried prestige but no regular income. Being an Ordinary Groom did supply some benefit in kind in an entitlement to livery. As a member of The Queen’s Players, he was not permanently resident at court, as the acting troupe toured, nor was he wholly dependent on acting for his income – with his wife, Kate, he also owned and let a tavern in Gracious Street, an ordinary (a tavern which serves meals) in Paternoster Row, and he wrote plays, broadsides and books (described in the second and third articles). It may have been that, as an Ordinary Groom, Tarlton employed his wit as Fuller described but, if so, it is difficult to see how anyone who wasn’t there would know, and how this account could be verified.

A popular posthumous account of Tarlton’s wit was published in three parts, the first in 1600: Tarltons Iests [Jests]. Drawne into these three parts. 1 His Court-wittie Iests 2 His sound Citie Iests. 3 His Country prettie Iests. Full of Delight, Wit, and Honest Myrth. It includes stories of Tarlton’s clowning at court, entertaining the Queen outside of his stage role in The Queen’s Men. For reasons explored in the second article, these accounts are not to be taken at face value, so verification is needed that Tarlton did indeed play a solo jesting role at court, and this is found in a surviving scrap of paper from August 1588, now collected in the British state papers. It describes one incident in which Richard entertained the Queen with his physical comedy, using her dogs as comedy partners: “How Tarlton played the God Luz with a flitch of bacon at his back, and how the Queen bade them take away the knave for making her to laugh so excessively, as he fought against her little dog, Perrico de Faldas, with his sword and long staffe, and bade the Queen take off her mastie [mastiff dog]; and what my Lord Sussex and Tarlton said to one another. The three things that make a woman lovely.”

Tarleton may rightly be described, then, as a stage clown and court jester. He was not the modern stereotype in a costume of asses’ ears and bells, but he did have a distinctive way of dressing to signify his status as an artifical fool.

Tarleton’s appearance

The portrait of Richard Tarleton below is in an alphabet book by John Scottowe. Since the praising poem on the page (which will be examined below) was written in tribute after the comedian’s death, it must be dated 1588 or later. The fact that the letter T has an image of and poem about Tarleton tells us of his popularity and immediate physical recognisability.

The image is remarkably similar to that used for the earliest surviving copy of Tarltons Iests. The cover of the 1613 edition, on the right, has him in the same pose, similarly dressed, and with the same full moustache, short pointed beard and curly hair. This woodcut is so like Scottowe’s portrait that one must be based on the other, or both based on a common original.

The image is remarkably similar to that used for the earliest surviving copy of Tarltons Iests. The cover of the 1613 edition, on the right, has him in the same pose, similarly dressed, and with the same full moustache, short pointed beard and curly hair. This woodcut is so like Scottowe’s portrait that one must be based on the other, or both based on a common original.

Robert Wilson’s aforementioned play, the three Lordes and three Ladies of London, 1590, performed 2 years after Tarlton’s death, makes a clear reference to an image of Tarlton on a broadside ballad, as follows.

Wea[lth]. What daintie fine Ballad haue you now to be sold?

Sim[plicity]. Marie child, I haue chipping Norton a mile from Chappell othe heath, A lamentable ballad of burning the Popes dog: The swéet Ballade of the Lincoln:shire bagpipes, And Peggy and Willy, But now he is dead and gone: Mine own sweet Willy is laid in his graue la, la, la, lan ti dan derry, dan da dan, lan ti dan, dan tan derry, dan do.

Wit· It is a dolefull discourse, and sung as dolefully …

Here simp. sings first, and Wit after, dialoguewise, both to musicke if ye will …

wil[l]. I pray ye honest man, what’s this?

Sim. Read and then shalt see.

wil. I cannot read.

Sim. Not read & brought vp in London, wentst thou neuer to schole

wil. Yes, but I would not learn.

Sim. Thou wast the more foole: if thou cannot read Ile tel thée, this is Tarltons picture: didst thou neuer know Tarlton? …

O it was a fine fellow as ere was borne,

there will neuer come his like while the earth can corne.

O passing fine Tarlton I would thou hadst liued yet.

Wea[lth]. … there is no such finenes in the picture that I see.

sim. … the finenes was within, for without he was plaine

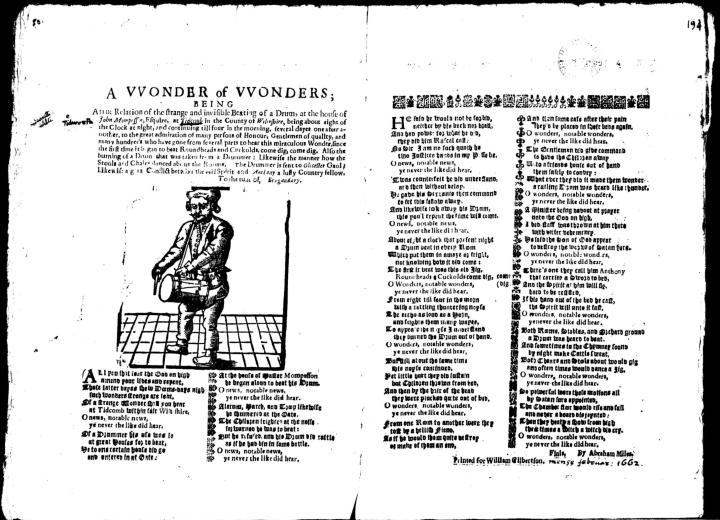

This passage makes clear that Tarlton’s likeness circulated as a woodcut printed on a broadside. Since woodcuts were used multiple times on a range of publications, it is almost certain that the image of Tarlton referred to in the play was the same as that used on the cover of Tarltons Iests, 1600 (shown above), and used again on the ballad of a ghost drummer, A Wonder of Wonders, 1662 (below).

at the house of John Mompesson, Esquire, at Tidcomb in the County of Wiltshire, a broadside ballad

of 1662, illustrates the story of a ghostly drummer with the familiar woodcut of Richard Tarlton.

The broadside is now in the Bodleian Library, Bod 18714

Wher’s Tarleton?, a poem in Quips upon Questions, or, A Clowenes conceite on occasion offered, 1600, published under the pseudonym Clunnyco de Curtanio Snuffe (Clown at the Curtain Theatre, i.e. Robert Armin of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, for whom Shakespeare acted and wrote), almost certainly refers to the same play and the same image in the lines,

Within the Play past, was his [Tarlton’s] picture vsed,

Which when the fellow saw, he laught aloud …

The simple man was quiet, and departed.

And hauing seen his Picture, was glad harted.

It is significant that the image chosen to represent Richard Tarleton was in musical performance on pipe and tabor. As we will see in the third article, music was integral to his comedy.

John Scottowe’s poem, next to his depiction of Tarleton in his alphabet book, reads as follows. In the second verse, “Counterfet” (counterfeit) means imitation or acting; and “sturtups” or startups are the ankle-length or calf-length boots we see Tarleton wearing in the image.

The picture here set down

The picture here set down

within this letter T

Aright doth shew the forme & Shap

of Tharlton unto the.

When hee in pleasaunt wise

The Counterfet expreste

of Clowne w[i]t[h] cote of russet hew

and sturtups with the reste.

Whoe merry many made

when he appeard in sight

The grave and wise as well as rude

at him did take delight.

The partie now is gone,

and closlie clad in claye,

Of all the Jesters in the lande

he bare the praise awaie

Now hath he plaid his p[ar]te

and sure he is of this

If he in Christe did die to live

with him in lasting blis.

John Scottowe’s description of Tarlton wearing a character costume, “The Counterfet expreste of Clowne”, is confirmed by the posthumous anonymous fantasy, Tarltons News out of purgatorie, 1600, that he was “artificially attyred for a Clowne”, by Tarltons Iests, that “Tarlton was in his clownes apparel”, and in Greenes Newes both from Heaven and Hell by B. R., 1593, in which “in comes Dick Tarlton, apparrelled like a Clowne”.

The stock idea of the country fool, the lower class rural bumpkin, had been a comedy commonplace since well before the middle ages. In the 16th century, the idea was carried visually in theatrical foolery by clothes and colour, and it was this part that Tarlton played. His “clownes apparel” included the startups mentioned in Scottowe’s second verse, leather boots up to the ankle or calf, worn by rural men and women to give protection from the mud and weather. On his legs he wore loose-fitting breeches called slops, likewise associated with country living. Slops came in various lengths and degrees of bagginess, and the long straight slop and startups worn by Tarleton was a combination also worn by mariners. The association of Tarlton with slops is confirmed by The Prologue in William Percy’s play, The cuck-queanes and cuckolds errants, 1601, in which Tarlton’s ghost speaks of having “My Drum, my Cap, my Slop, my Shooe, yea that same old and merry Mr Tarlton”. In the anonymous The Partiall Law: a tragic-comedy, c. 1615–1630, a dance tune is described as being “as old as the beginning of the world, or Tarlton’s Trunk-hose”, suggesting that the slops of Tarlton’s comic country character affected an age-worn look. (This is a play on words so beloved of the period, as the beginning of the world and Tarlton’s Trunk-hose are also tune titles, as we will see in the third article about Tarlton the musician.) In Samuel Rowland’s pamphlet, The Letting of Humours Blood in the Head-Vaine, 1600, he wrote satirical verses in which he compared fashionable gallants’ wearing of slops to the famous clown:

When Tarlton clown’d it in a pleasant vaine

With conceites did good opinions gaine

Upon the stage, his merry humours shop.

Clownes knew the Clowne, by his great clownish slop.

But now th’are gull’d, for present fashion sayes, gull’d: duped, fooled

Dick Tarletons part, Gentlemens breeches plaies:

In every streete where any Gallant goes,

The swagg’ring Sloppe, is Tarltons clownish hose.

Sir Thomas Wright’s treatise, The Passions of the Minde, 1601, gives a more detailed and deliberately ludicrous description: “some times I have seene Tarleton play the Clowne, and use no other breeches than such sloppes, or slivings, as now many Gentlemen weare, they are almost capable of a bushell of wheate, and if they bee of sacke-cloth, they woulde serve to carrie mawlt to the Mill.”

head”: a fool in russet wearing a buttoned cap, from an

anonymous Flemish satirical diptych, early 16th century.

Working our way up Scottowe’s image, the poem describes Tarleton’s “cote of russet hew”. Tarltons News out of purgatorie, 1600, confirms the jacket colour, cap, and bag: “I saw one attired in russet with a buttond cap on his head, a great bagge by his side, and a strong bat in his hand, so artificially attired for a clowne as I began to call Tarlton’s wonted shape to remembrance”. Similarly, Henry Chettle, in his Kind-Hartes Dreame, 1592, confirms the colour and other details: “by his sute of russet, his buttoned cap, his taber, his standing on the toe, and other tricks, I knew to be either the body or resemblaunce of Tarlton, who liuing for his pleasant conceits was of all men liked, and dying, for mirth left not his like.”

The title of William Rankins’ work of 1587 leaves the reader in no doubt of his view of the theatre: A mirrour of monsters wherein is plainely described the manifold vices, &c spotted enormities, that are caused by the infectious sight of playes, with the description of the subtile slights of Sathan, making them his instruments. Rankins doesn’t mention Dick Tarleton, but in his sweeping condemnation of all players he does state that red-brown russet was the recognised colour worn by artificial fools playing the part of a country clown: “theyr Clownes cladde as well with Country condition, as in Ruffe russet”. Among many witnesses to confirm the association of rural russet with artificial fools or clowns is the royal order in 1565 of clothes for Jack Grene, the first person to be named Queen Elizabeth’s artificial fool: “a payre of Hose of russet clothe for Jacke our said foule with lyninges of lynnen … for making of a payre of sloppes of fryse trimmed with red frendge”, along with other clothes in “sundry collors”.

This is not to state that startups, old slops, bag, russet coat, buttoned cap, and pipe and tabor was Tarlton’s only look. As we will see in the second article, he wore whatever the role demanded; and when his clown’s role was required, as it often was and for which he was most fondly remembered, his stylised country clown clothes were his recognised trademark.

Tarlton’s physical form, as well as his clothes, was the subject of comment. We have seen above the remark in Robert Wilson’s play, the three Lordes and three Ladies of London, that “the finenes was within, for without he was plaine”.

Tarlton’s physical form, as well as his clothes, was the subject of comment. We have seen above the remark in Robert Wilson’s play, the three Lordes and three Ladies of London, that “the finenes was within, for without he was plaine”.

Two witnesses, both dated 1600, make the same observation about one of Tarlton’s eyes. In Quips upon Questions, Robert Armin, who very likely knew Tarleton personally, wrote of “the squint of Tarletons eie”, and in the first of Tarltons … sound Citie Iests, Tarlton’s iest of a red face, we read that “the gentlemen and gallants, they enquired of him why melancholy had got the upper hand of his mirth. To which he said little, but, with a squint eye, as custome had made him hare eyed, hee looked for a jest to make them merry.” The term “hare eyed” has, since its use by the Roman encyclopaedist Aulus Cornelius Celsus in the 1st century CE, referred to lagophthalmos, a medical condition of the upper or lower eyelid or both, which prevents the eyelids from completely closing. Lagophthalmos can be genetic or a result of trauma to facial nerves. If the latter, its cause may be related to the only story in Tarltons Iests written by the anonymous author in the first person. This singular eye-witness account concerns the after-play jig – the light-hearted and humorous performance which included stories, dances and songs – and Tarlton’s nose.

“Tarlton’s answer in defence of his flat nose

I remember I was once at a play in the country, where, as Tarlton’s use was, the play being done, every one so pleased to throw up his theame [shout out themes for Tarlton to create extempore songs] : amongst all the rest, one was read to this effect, word by word : –

Tarlton, I am one of thy friends, and none of thy foes.

Then I prethee tell how cam’st by thy flat nose :

Had I beene present at that time on those banks,

I would have laid my short sword over his long shankes.

Tarlton mad at this question, as it was his property sooner to take such a matter ill then well, very suddenly returned him this answere : –

Friend or foe, if thou wilt needs know,

Marke me well :

With parting dogs and bears, then, by the ears,

This chance fell:

But what of that?

Though my nose be flat,

My credit to save,

Yet very well, I can by the smell,

Scent an honest man from a knave.”

The story tells us that Tarlton was sensitive about his flattened nose, and perceived – rightly or wrongly – that the audience member knew this and was trying to goad him, not “an honest man [but] a knave”, so his versified reply is an angry retort rather than comedy; and that his nose was damaged defending his financial interest in bear baiting. Bear baiting, present in England since the middle ages, became big business in the mid-16th century when permanent venues for animal fights became established, for example, on the south bank of the Thames. It wasn’t only bears: bets were placed on dogs, bulls, chimpanzees and other animals in their fight to the death for human entertainment, and this bloody spectacle was the chief commercial competition for the theatre. As we see below in the detail from Claes Visscher’s engraving, Londinium Florentissima Britanniae Urbs, The Bear Gardens and The Globe were neighbours on the bank of The Thames. It wasn’t only the pastime of commoners: Queen Elizabeth organised bear-baiting for the visit of the French ambassador, and King James I used the Tower of London’s animal menagerie as stock for private shows pitting polar bears against lions.

showing The Bear Gardens and The Globe as neighbours on the bank of The Thames.

Though hugely popular in the 16th and 17th centuries, such blood sports had their critics. Some of the clergy attacked it, not for its brutal cruelty, but for its association with sinfulness: gambling on the outcome was a vice, associated with drunkenness and prostitution. Others recognised its inherent violence. The English diarist John Evelyn visited The Bear Gardens in 1670 and denounced the games as a “rude and dirty pastime” of “barbarous cruelties.”

Fechthaus, an entertainment venue in

Nürnberg, being used as an animal baiting

arena: dogs are set on a bull while more

dogs attack a bear tied to a stake.

Bear-baiting was the most popular animal ‘entertainment’: a bear in a pit was chained to a stake by the neck or leg and attacked by a pack of bulldogs or mastiffs. The winner was the bear if s/he killed several dogs, or the dogs if the bear was bitten into defeat. Since bears were imported from abroad and therefore expensive, it was in the interests of organisers to make sure the bear didn’t die in the pit. Since Tarlton’s riposte in the jig was that “With parting dogs and bears, then, by the ears … my nose be flat, My credit to save”, he was involved financially in bear-baiting and was protecting his investment by pulling the dogs off a bear, attacked himself by one or more of the unfortunate animals in the process.

We have seen from his pre-performance years as a water-bearer, and from Henry Chettle’s description of “his standing on the toe, and other tricks”, that Tarleton must have been a physically strong and capable man. This is further confirmed by his intervention in bear-baiting and by his participation in a fight in 1583 at the Red Lion Inn in Norwich, when a performance by The Queen’s Men became a violent brawl. There are several surviving testimonies, which all agree in substance. William Kylbye described how “hee dyd see three of the players rvnne of the stage with there swordes in there handes”; George Jackson referred to “one of the players in his players apperrell with a players berd vppon his face with a sworde or a raper in his hand drawen”; and Edmunde Brown remembered “the gate-keper and hee stryvynge, Tarleton came out of the stayge, and would have thrust hym out at the gate, but in the meane tyme one Bentley, he wich played the Duke, came of the stage, and with his hiltes of his sworde he strooke Wynsdon upon the heade, and offered hym another strype, but Tarleton defended yt, whereupon Wynsdon fled out of the gate.”

Remembering Richard rightly

We have seen that Richard Tarleton was a jester, meaning an artificial fool, a professional clown. As John Scottowe expressed it in his poetic tribute, he was remembered as the very greatest stage clown:

Of all the Jesters in the lande

he bare the praise awaie

The modern conception of the jester is that of a pied-costumed, ass-eared, coxcombed royal servant, an idea based largely on iconographical convention, reinforced by modern assumptions rather than actuality. In reality, when “artificially attyred for a Clowne”, Tarlton played pipe and tabor and wore a buttoned cap, russet jacket, slops and startups, the comedic image of a country fool. Thus dressed, he was a royal appointee as a member of The Queen’s Players, and a solo jester or artifical fool for the Queen at court.

He came from working class origins, a London water-bearer (not, as stated by Thomas Fuller, a Shropshire pig farmer). His strength meant that he was good in a brawl, that “his standing on the toe, and other tricks” were part of his physical comedy, and that he was confident enough to intervene in bear-baiting, resulting in permanent physical injury.

As we will see in the second article about Tarleton the player and playwright, his skill as a comic actor was much-loved, much written about, and much-missed after his sudden death. Neglected in both historical and modern accounts has been Tarleton’s skill as a serious actor, playwright and poet/essayist, so the second article includes his affecting role as a prodigal son and a reconstruction of one of Tarleton’s lost plays, The Secound parte of the Seven Deadlie Sinns. Equally neglected in modern accounts is Richard Tarleton the musician, the subject of the third article, which explains the nature of his comedic extempore songs and describes his religious/moralistic verse. The fourth article surveys posthumous tributes and includes, reuniting for the first time (as far as I am aware) the words and music of a broadside ballad written in homage, the tune previously and wrongly ascribed to John Dowland, the melody of which may well have been played by Tarleton in his after-play jigs.

© Ian Pittaway. Not to be reproduced in any form without permission. All rights reserved.

Bibliography

Andrews, Evan (2019) The Gruesome Blood Sports of Shakespearean England. Available online by clicking here.

Anonymous (1338–44) Romans d’Alexandre, Bodleian Library MS. Bodl. 264. Available online by clicking here.

Anonymous (1600) Tarltons newes out of purgatorie Onely such a iest as his iigge, fit for gentlemen to laugh at an houre, &c. Published by an old companion of his, Robin Goodfellow. Available online by clicking here.

Anonymous (c. 1615–30, this edition 1908, with an introduction by Bertram Dobell) The Partiall Law, A Tragi-Comedy. London: Bertram Dobell. Available online by clicking here.

Barber, Richard (1992) Bestiary, MS Bodley 764. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press.

Barroll, Leeds (editor) (1995) Shakespeare Studies Volume XXIII. Cranbury, NJ: Associated University Presses.

Baskervill, Charles Read (1929) The Elizabethan Jig and Related Song Drama. New York: Dover Publications.

Belfield, Jane (1978) Tarlton’s News Out of Purgatory (1590) A Modern-spelling Edition, with Introduction and Commentary. Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Birmingham Shakespeare Institute, October 1978. Available online by clicking here.

Bodleian Library (undated) Broadside Ballads Online from the Bodleian Libraries. Available by clicking here.

B. R. (1593) GREENES Newes both from Heauen and HelL Prohibited the first for writing of Bookes, and banished out of the last for displaying of Conny-catchers. Commended to the Presse By B. R. Available online by clicking here.

Brant, Sebastian (1494, translated 1944) The Ship of Fools, translated into rhyming couplets with introduction and commentary by Edwin H. Zeydel. New York: Dover.

British History Online (2019) References to Tarlton. Available online by clicking here.

British Library (2015) Robin Goodfellow, His Mad Pranks and Merry Jests, 1639. Available online by clicking here.

British Library (2015) The Terrors of the Night by Thomas Nash, 1594. Available online by clicking here.

Campbell, Lily B. (1941) Richard Tarlton and the Earthquake of 1580. Huntington Library Quarterly, Vol. 4, No. 3 (April 1941), pp. 293-301. Available online by clicking here.

Cavendish, William (1649) The Country CAPTAINE, And the VARIETIE, Two COMEDIES, Written by a Person of HONOR. Lately presented by His MAJESTIES Servants, at the Black-Fryers. Available online by clicking here.

Chettle, Henry (1592) Kind-Hartes Dreame. Available online by clicking here.

Clark, Andrew (1907) The Shirburn Ballads 1585–1616. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Available online by clicking here.

Crystal, David & Crystal, Ben (2002) Shakespeare’s Words. A Glossary & Language Companion. London: Penguin.

Dickson, Wilma Ann (1987) The rhetoric of religious polemic: a literary study of the church order debate in the reign of Queen Elizabeth I. Doctoral thesis, Durham University. Available online by clicking here.

Elgin, Kathy (2005) A History of Fashion and Costume. Volume 3. Elizabethan England. Hove: Bailey Publishing. Available online by clicking here.

Ellis, Sir Henry (1798) The history and antiquities of the parish of St. Leonard Shoreditch, and liberty of Norton Folgate, in the suburbs of London. London: J. Nichols. Available online by clicking here.

English Broadside Ballad Archive. Available online by clicking here.

Forrest, John (1999) The History of Morris Dancing, 1458-1750. Cambridge: James Clarke.

Fuller, Thomas (1648, this edition 1840) The Holy State and the Profane State. London: William Pickering. Available online by clicking here.

Fuller, Thomas (published posthumously in 1662, this edition 1811) The history of the worthies of England. A new edition, in two volumes. Vol. II. London: John Nichols and Son. Available online by clicking here.

Gaskell, Ian (2009) The Matthew Holmes Consorts. The Cambridge Consort Books c.1588–?1597. Available online by clicking here.

Graves, Thornton S. (1921) Some Allusions to Richard Tarleton. Modern Philology, Vol. 18, No. 9 (Jan. 1921), pp. 493-496. Available online by clicking here.

Greenblatt, Stephen; Cohen, Walter; Howard, Jean E.; Eisaman Maus, Katharine; Gurr, Andrew (1997) The Norton Shakespeare. New York: Norton.

Greene, Robert (1594, this edition 1907) The Historie of Orlando Furioso, one of the twelve Peeres of France. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Available online by clicking here.

Haig, Edward (undated) A Study of Satire in a Seventeenth Century Pamphlet. Available online by clicking here. (This source is useful for some information about Pigges Corantoe, but the historical meaning it gives to the word corantoe and to possible historical events behind “old Tarltons song” are confused and misleading.)

Halliwell, James Orchard (1844) Tarlton’s Jests, and News Out of Purgatory, with notes, and some account of the life of Tarlton. London: The Shakespeare Society. Available online by clicking here or here or here. (Note that Halliwell’s introduction includes a song, Tarlton’s Jigg of a horse loade of Fooles, purportedly 16th century and before Tarlton’s death, which was later shown to be a forgery by its ‘finder’, John Payne Collier.)

Halliwell, James Orchard (1886) The Nursery Rhymes of England. London and New York: Frederick Warne and Co. Available online by clicking here.

Harper, Sally (2005) An Elizabethan Tune List from Lleweni Hall, North Wales. Royal Musical Association Research Chronicle, No. 38, pp. 45-98.

Holl, Jennifer (2019) “The wonder of his time”: Richard Tarlton and the Dynamics of Early Modern Theatrical Celebrity. Historical Social Research / Historische Sozialforschung. Celebrity’s Histories: Case Studies & Critical Perspectives, Supplement No. 32, pp. 58-82. Available online by clicking here.

Howes, Edmund (1631) Annales, or, a generall Chronicle of England. Begun by Iohn Stow: Continved and Augmented with matters Forraigne and Domestique, Ancient and Moderne, vnto the end of this present yeere, 1631. Available online by clicking here.

Huth, Alfred Henry (ed.) (1867) A Collection of Seventy-Nine Black-Letter Ballads and Broadsides, printed in the reign of Queen Elizabeth, 1559-1597. A new edition of ‘Ancient Ballads and Broadsides published in English in the 16th century.’ London: British Library.

Hutton, Ronald (1994) The Rise and Fall of Merry England: The Ritual Year, 1400-1700. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ishikawa, Naoko (2011) The English Clown: Print in Performance and Performance in Print. A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The Shakespeare Institute, The Department of English, The University of Birmingham. Available online by clicking here.

Jakacki, Diane (2020) The Tarlton Project. Available online by clicking here.

J. S. (1651) An excellent comedy, called, The Prince of Priggs revels: or, The practises of that grand thief Captain James Hind, relating divers of his pranks and exploits, never heretofore published by any. Repleat with various conceits, and Tarltonian mirth, suitable to the subject. Available online by clicking here.

Kathman, David (2004) Reconsidering The Seven Deadly Sins. Early Theatre, Vol. 7, No. 1. Available online by clicking here.

Keenan, Siobhan (1999) Provincial Playing Places and Performances in Early Modern England, 1559-1625. Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Warwick, Centre for the Study of the Renaissance. Available online by clicking here.

Kemp, William (1600) Kemps nine daies vvonder. Performed in a daunce from London to Norwich. Containing the pleasure, paines and kinde entertainement of William Kemp betweene London and that Citty in his late Morrice. Wherein is somewhat set downe worth note; to reprooue the slaunders spred of him: many things merry, nothing hurtfull. Written by himselfe to satisfie his friends. Available online by clicking here.

Levin, Richard (1999) Tarlton in The Famous History of Friar Bacon and Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay. Medieval & Renaissance Drama in England, Vol. 12, pp. 84-98. Available online by clicking here.

Long, John H. (1970) The Ballad Medley and the Fool. Studies in Philology, Vol. 67. Available online by clicking here. (Though this essay includes valuable information about the medley form, some of John H. Long’s claims should be approached with caution. For example, he states that “Apparently, Tarleton used the ballad medley extensively” and “we find the medley an almost inseparable companion of the stage fool Tarleton”, without providing any substantiating evidence.)

MacGregor, Neil (2014) Shakespeare’s Restless World. London: Penguin.

Marprelate, Martin [pseudeonym] (1589) Hay Any Work For Cooper. Or a brief pistle directed by way of an hublication to the reverend bishops, counselling them if they will needs be barrelled up for fear of smelling in the nostrils of her Majesty and the state, that they would use the advice of reverend Martin for the providing of their cooper. Because the reverend T. C. (by which mystical letters is understood either the bouncing parson of East Meon, or Tom Cook’s chaplain) hath showed himself in his late Admonition To The People Of England to be an unskilful and beceitful tub-trimmer. Wherein worthy Martin quits himself like a man, I warrant you, in the modest defence of his self and his learned pistles, and makes the Cooper’s hoops to fly off and the bishops’ tubs to leak out of all cry. Penned and compiled by Martin the metropolitan. Available online by clicking here.

McAbee, Kris & Murphy, Jessica C. (2007) Ballad Creation and Circulation: Congers and Mongers. Available online by clicking here.

McIlvenna, Una (2012) A Woeful Sinner’s Fall: ballads of execution. Broadcast on Into The Music, ABC Radio National, on 15th December 2012. Available online by clicking here.

McInnis, David (2012) Evidence of a Lost Tarlton Play, c. 1585, probably for the Queen’s Men. Notes and Queries. Vol. 59, No. 1 (March 27, 2012), pp. 43-45. Available online by clicking here.

Morris Ring (undated) Morris History – Before the Restoration. Morris Before The Restoration of Charles II in 1660. Available online by clicking here.

Nash(e), Thomas (1592) Pierce Penilesse His Supplication to the Devil. Describing the overspreading of vice, and suppression of virtue. Pleasantly interlaced with variable delights, and pathetically intermixed with conceited reproofs. Available online by clicking here.

Nashe, Thomas (1592) Strange Newes, Of the intercepting certaine Letters, and a Conuoy of Verses, as they were going Priuilie to victuall the Low Countries. Available online by clicking here. Modern spelling version available by clicking here.

Nebeker, Eric (2007) Ballad Sheet Sizes. Available online by clicking here.

Peacham, Henry (1634, 1638, 1642; this anthology 1962) The complete gentleman, The truth of our times and The art of Living in London. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press for the Folger Shakespeare Library. Available online by clicking here.

Percy, William (1601, this edition 1824) The cuck-queanes and cuckolds errants, or, The bearing down the inne. A comaedye. Available online by clicking here.

Poulton, Diana (1982) John Dowland. Second edition. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Preiss, Richard (2014) Clowning and Authorship in Early Modern Theatre. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rankins, William (1587) A mirrour of monsters wherein is plainely described the manifold vices, &c spotted enormities, that are caused by the infectious sight of playes, with the description of the subtile slights of Sathan, making them his instruments. Available online by clicking here.

Rasmussen, Eric, & DeJong, Ian (2016) Shakespeare’s London. Available online by clicking here.

Rastell, John (1510–20, this facsimile edition 1908) A new interlude and a mery of the nature of the .iiii. elements. London: Issued for subscribers by T. C. & E. C. Jack. Available online by clicking here or here.

Robinson, John (2018) Music Supplement to Lute News 127 (October 2018). Guildford: The Lute Society.

Rollins, Hyder E. (1967) An analytical index to the ballad-entries (1557-1709) in the registers of the Company of Stationers of London. Hatboro, Pennsylvania: Tradition Press.

Saunders, Anthony (2014 ) Italian Rapier Play c. 1570–1620. Available online by clicking here.

Scottowe, John (after 1588) Alphabet book, British Library Harley 3885. Available online by clicking here.

Sharp, Cecil J. & MacIlwaine, Herbert C. (1907) The Morris Book. A history of morris dancing with a description of eleven dances as performed by the morris-men of England in two parts. Part I. London: Novello and Company. Available online by clicking here.

Simpson, Claude M. (1966) The British Broadside Ballad and Its Music. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Smith, Douglas Alton (2002) A History of the Lute from Antiquity to the Renaissance. Massachusetts: Lute Society of America.

Southworth, John (1998) Fools and Jesters at the English Court. Stroud: Sutton Publishing.

Spring, Matthew (2001) The Lute in Britain. A history of the instrument and its music. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stradling, John (1607) Epigrammatum Libri Quatuor. Available online by clicking here.

Tarleton, Richard (c. 1585) MSS 19 – The ‘Platt’ (or Plot) of The Second Part of the Seven Deadly Sins 1612-1626. Available at The Henslowe-Alleyn Digitisation Project by clicking here.

Thorpe, Vanessa (2015) Actor who plays Archers villain in shock at social media onslaught. Available online by clicking here.

Wager, William (c. 1568, this facsimile edition 1910) The longer thou liuest the more fool thou art. Issued for subscribers by the editor of the Tudor facsimile texts. Available online by clicking here or here.

Welsford, Enid (1935) The Fool: His Social and Literary History. New York: Faber & Faber.

Williams, Sir Roger (1590) A Briefe discourse of Warre. Written by Sir Roger Williams Knight; With his opinion concerning some parts of the Martiall Discipline. Available online by clicking here.

Wilson, Robert (1590) The pleasant and stately morall, of the three lordes and three ladies of London With the great ioy and pompe, solempnized at their mariages: commically interlaced with much honest mirth, for pleasure and recreation, among many morall obseruations and and other important matters of due regard. by R.W. Available online by clicking here and in facsimile here.

Winchcombe, Alys (2015) Henry VIII and the harp. Available online by clicking here.