Early music and dance enthusiasts will be familiar with the work of authors such as John Playford, who published the series of dance instruction books called The (English) Dancing Master from 1651 onwards, and with Jehan Tabourot, who in 1588 wrote instructions for the dances of his youth under the anagrammatic pen name, Thoinot Arbeau, published in France as Orchésographie in 1589. There is evidence of earlier dancing masters – dance instructors – from the medieval period, but the first to write surviving choreography were in the renaissance of 15th century Italy, and the earliest of these was Domenico da Piacenza (c. 1390/1400–1476/7). This article briefly outlines Domenico’s dance manual of c. 1450, the social context of his dances, his wide influence, and some ways in which his choreography and music notation can be interpreted using one example, La giloxia (The jealousy), a video of which begins this article.

Early music and dance enthusiasts will be familiar with the work of authors such as John Playford, who published the series of dance instruction books called The (English) Dancing Master from 1651 onwards, and with Jehan Tabourot, who in 1588 wrote instructions for the dances of his youth under the anagrammatic pen name, Thoinot Arbeau, published in France as Orchésographie in 1589. There is evidence of earlier dancing masters – dance instructors – from the medieval period, but the first to write surviving choreography were in the renaissance of 15th century Italy, and the earliest of these was Domenico da Piacenza (c. 1390/1400–1476/7). This article briefly outlines Domenico’s dance manual of c. 1450, the social context of his dances, his wide influence, and some ways in which his choreography and music notation can be interpreted using one example, La giloxia (The jealousy), a video of which begins this article.

La giloxia (The jealousy), music and dance by Domenico da Piacenza, from

De arte saltandi & choreas ducendi (The art of dancing & choreography), c. 1450.

The music is played by Paul Baker, recorder, and Ian Pittaway, lute, and danced by

Saltus Gladii, Lithuania, and Soubor Anello (Ensemble Anello), Czech Republic.

Many thanks to Saltus Gladii and Marie Vozková on behalf of Soubor Anello

for permission to use their dance videos.

Recreating medieval dance

The level of difficulty in reconstructing something from a medieval source depends on the surviving material. With paintings, we have the object and the material used to create it: brushstrokes can be studied, paint pigments can be analysed, and thus the method of its construction can be recreated. Medieval music is more tricky. When we have the object – a manuscript with music notation – we do not have the material used to create it – the medieval voice or other instruments – so our analysis can only go as far as written accounts of performance will take us, and we’re still left to interpret the medieval understanding of their descriptions of a “sweet”, “loud” or “bitter” voice.

In contrast with both examples, the recreation of any medieval dance is impossible. We have neither the object – a living dance instructor or written dance instructions – nor the material used to create it – medieval dancers. When writers did describe dances, they wrote with such a dearth of detail that it always begs more questions that it answers, so the ephemeral and transient movements of long-dead dancers leave us nothing to be studied except vague descriptions in writing and the static bodies of dancers in art, hinting at movements that are lost, keeping their secrets, not yielding to us visually even the type of dance being performed, nor the pace, nor what comes before or after the moment the artist has frozen in time.

The detail above from Allegory of Good Government by Ambrogio Lorenzetti, painted 1338-40, illustrates the problem with reconstructing medieval dance. Some details are beautifully clear. We see that all the dancers are women, that the music is provided by a single woman who sings while playing timbrel, and that this dance figure, with a single line moving under a single-handed arch, looks very much like the ceilidh figure today called thread the needle. Other details are impossible to judge from a single static image. How are the feet and legs moving as they progress? What speed are they dancing? Are they dancing forward under the arch, or backwards? What is the music for this dance? Is the singer vocalising a textless melody or singing the words of a song? What dance type is it? Did this dance type only ever include women, or could it be mixed or danced by men alone? What happens in the dance before and after this figure?

There were medieval dancing masters, but what they taught is lost with the unwritten memories of the dancers. We have the name of only one: in 1313, Rabbi Haçen ben Salomo taught a dance to the congregation of Saint Bartholomew’s Church, Zaragoza, Spain, but neither the choreography nor the music was recorded. It is only from the renaissance onwards that dance instructions survive, and the earliest in surviving records are in Domenico da Piacenza’s manuscript of c. 1450, De arte saltandi & choreas ducendi (The art of dancing & choreography).

Domenico da Piacenza

Domenico da Piacenza – also known as Domengo da Piacenza, Domenico da Ferrara, Domenichino, or Domenegino – was born c. 1390-1400 in Piacenza, and worked in northern Italian cities – Milan, Modena, Faenza, Forlì, and Ferrara. He died in Ferrara in 1476/7.

painted by Giovanni da Oriolo, c. 1447.

The d’Estes were Ferrara’s ruling family from the 13th to the 16th century. Leonello d’Este, who was to be Domenico’s patron, ruled as Marquis of Ferrara and Duke of Modena and Reggio Emilia from 1441 to 1450. Leonello made Ferrara an international centre of humanist culture. The city attracted and employed painters in the new renaissance style such as Jacopo Bellini and Antonio di Puccio Pisano (Pisanello) and the polymath architect Leon Battista Alberti. In 1436, under Leonello’s patronage, Guarino da Verona became Professor of Greek at Ferrara. For five years, Guarino had been a pupil of Manuel Chrysoloras, a pivotal figure who furthered the values of the Italian renaissance by reintroducing the Greek language to Italy, which had not been studied there for 700 years (as this article explains).

Domenico’s first contact with Leonello d’Este may have been through Leonello’s marriage to Margherita Gonzaga in 1435. It is possible that Domenico’s dance, Lioncello Novo, was created for the wedding of Leonello and Margherita. In 1439, Domenico first appears in the d’Este court registers of the mandati (ambassadors/diplomats), paid for his services as dancing master. His name reappears in the records of the salariati (employees) of the d’Este court until the end of 1472, then again through 1475, near to his death in 1476/7.

The record of monthly salaries for the year 1456 under Borso d’Este, Leonello’s successor, is particularly interesting. Along with Domenico’s name we are given the identities and instruments of court musicians. They are the Italian master of the lute, gittern and cetra, Pietrobono; the lutenist Niccolò Todescho (Nicholas the German, who appears in salary records first as a singer in 1436, and continues to appear until 1481); the German shawm player, Corrado de Alemagna; a second German shawm player, unnamed; an unspecified number of unnamed trumpeters; and an unnamed harpist. This potentially makes Domenico’s dance instrumentation a choice from two lutes, two shawms, trumpets, and a harp.

Domenico da Piacenza’s skill and reputation as a dancing master was such that his students became great dancing masters themselves. Domenico’s student, Antonio Cornazano (or Cornazzano), wrote his own dance manual in 1455, Libro dell’arte del danzare (Book of the art of dancing). Guglielmo Ebreo (William the Jew) came to live in Milan to study with Domenico, and he wrote his own treatise in 1463, De pratica seu arte tripudii (On the practice or art of dancing). His patron, Alessandro Sforza, Lord of Pesaro, convinced Guglielmo to convert to Roman Catholicism and so, between 1463 and 1465, he was baptised and was thereafter known as Giovanni Ambrosio. Under this latter name he updated his treatise in c. 1470. Both Antonio Cornazano and Guglielmo Ebreo / Giovanni Ambrosio acknowledge their debt to Domenico in their own works, thus adding to their credibility as dancing masters by association with “the master of the art”.

For his services to dancing, Domenico was awarded a knighthood, the highest honour possible for a non-noble. Specifically, he was made a Knight of the Golden Spur, of the Order of the Golden Militia, in Italian, Militia Aurata, a title conferred by the Holy Roman Emperor. The date of the award is unknown, but is likely to have been 1452, when Emperor Frederick III visited Italy and presented many knighthoods, close in date to the production of Domenico’s De arte saltandi et choreas ducendi in c. 1450.

The social role of dance

For humanist renaissance writers of the 15th century on, dance was about far more than movement: it was about character-building, promotion of health, the perpetuation of social bonds, the appreciation of aesthetics, and thus it was an integral part of an all-round aristocratic education. Thus, when Jehan Tabourot, under his anagrammatic pen-name, Thoinot Arbeau, wrote in Orchésographie that, “quite apart from the many other advantages to be derived from dancing, it becomes an essential in a well-ordered society”, he was expressing in 1588 the view of dance that had been present in written accounts since Domenico in the mid-15th century.

Jehan Tabourot was the first in surviving records to describe popular urban dances, the social dances of 16th century France. In surviving 15th century Italian writings, dance was a way for the elite to distinguish and separate themselves from the ordinary masses, expressing refinement in movement, seeking novelty in order to communicate high-value uniqueness and rarity. In June 1469, Lorenzo de’ Medici was to be married to Clarice Orsini. Dancing master Filippus Bussus wrote to Lorenzo with a suggestion to emphasise their high status through dance (and through this means gain his employment): “And if you would like to learn two or three of these balli and a few bassadanze from me, I would come eight or ten days before the festivities to teach them to you with my humble diligence and ability; and in that way it will also be possible to teach your brother Giuliano and your sisters so that you will be able to acquire honour and fame in these festivities of yours by showing that not everyone has them [the dances], since they are so little known and rare.”

In his dance manual, Guglielmo Ebreo refers to popular festivals for which he choreographed the dances, but in their works Domenico da Piacenza and Antonio Cornazano refer only to teaching the elite. This class connection was critical to Domenico’s success, and to the fact that his work has survived: it was the elite who were literate. Domenico’s wife was Giovanna Trotto of the Trotto family, courtiers and ambassadors to the d’Estes. Given that marriage was based on status, we can say with certainty that Domenico was not a ‘poor boy made good’, but was born into the class who served the elite. In a milieu when no noble would dance with her social inferior it is telling that, as dancing masters, Guglielmo Ebreo danced with Isabella d’Este (the d’Estes were Ferrara’s ruling family), Antonio Cornazano with Ippolita Sforza (the Sforzas were the ruling family of Milan), and Domenico da Piacenza with Bianca Maria Sforza.

As dancing master to the aristocracy, Domenico was called upon to make their marriages lavish and memorable by choreographing unique wedding dances. For this reason, in 1455 Domenico was brought to Milan by Francesco Sforza for the wedding of his son Tristano Sforza to Beatrice d’Este. Later in the same year, he choreographed dances with Guglielmo Ebreo for Ippolita Sforza’s engagement to Alfonso d’Aragona. The two dancing masters worked together again in 1462 in Forlì for the wedding dances of Pino de Ordelaffi and Barbara Manfredi.

The d’Este family appointed Domenico as “maestro di buone maniere ed esperto danzatore” – master of good manners and experienced dancer. Besides dancing, a dancing master was tasked with teaching a rounded intellectual and artistic education focussed on physical movement and beauty: music, dance, athletics, fencing and riding. This reflects the fact that renaissance humanists led a cultural celebration of the human body. Leon Battista Alberti, 15th century Italian polymath, epitomised the approach when he wrote, “To you is given a body more graceful than other animals, to you power of apt and various movements, to you most sharp and delicate senses, to you wit, reason, memory like an immortal God.”

However, this celebration of the human form, most visually obvious in the revival of the art of classical Greek and Roman sculpture, expressed socially in the art of physical movement, had its moral dangers for those who thought in terms of the fate of their eternal soul. For this reason, the influential 15th century Italian educator Vittorino da Feltre warned that dance was only morally acceptable when its exertions did not lead to “laziness or sensual excitement”. (In the 16th century, the dance la volta was considered by many moral commentators to cross this line and excite Satanic lust.)

but the focus on the idealised human form brought moral dangers for humanist writers: appreciate

the human form God gave you, enjoy it in physical activity, but don’t get turned on. Left to right,

four examples of classical art celebrating the human form, loved and emulated in the renaissance:

Roman discobolus, c. 140 CE (National Roman Museum, Palazzo Massimo alle Terme);

Venus Genetrix, Roman Empire, 2nd century CE (J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles);

Hermes, Rome, 1st or 2nd century CE (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York); nymph resisting a satyr,

Rome, 2nd century CE copy of a 2nd or 1st century BCE Greek original (Portland Art Museum, Oregon).

What of the dances of the bourgeoisie and the land-working proles or peasantry? In his Libro dell’arte del danzare (Book of the art of dancing), 1455, Antonio Cornazano stated that the bourgeoisie were entertaining themselves with Domenico’s dances, suggesting a cultural imitation of the aristocracy by the middle class, and the distinct possibility that there were dancing masters making a living by serving middle class tastes. Of the common majority we can say little: being largely illiterate, and with no one in surviving records writing about them in any detail, their dances have been lost. We have only vague descriptions such as Florentine writers who mention young people on May Day festivals singing songs boisterously and dancing with lusty movements. This description may be indicative of the writer’s distinction between the mannered decorum of the aristocracy and the energetic rowdiness of the common people, using dance to suggest differences in culture and refinement, expressing a perception of the classes’ respective collective characters.

The scene above, filling folio 20v of The Hours of Charles of Angoulême, France, 1480-1496, is one of the few sources of 15th century peasant dance, and the stylised, still image leaves us with the same problems described above with all iconography of earlier medieval dance. This image by French illuminator and painter, Robinet Testard (fl. 1470-1531), is a late 15th century attempt to capture the dancing joy of the shepherds at the nativity. In the sky is a kneeling angel with Latin scrolls on either side, including the words, “Gloria in excelsis Deo” – Glory to God in the highest. Down on the ground, seven shepherds dance around a tree to a single bagpiper. Their dancing appears at first sight to be disorderly, but if the male dancer with his right knee forward is circling the other dancers back to place at the open part of the ring, we may imagine it to be a snapshot of choreography known to Testard. But this is speculation and not the only way to read the image. It would be fanciful to try and glean anything but unverifiable conjecture about choreography from this single page.

Domenico’s dance manual

Domenico wrote his book of dances in vernacular Italian rather than learned Latin so as to include all possible readers, including women, rather than only educated men. Domenico’s choreography, the earliest that survives, is detailed, but it is not a complete record. Assumptions are made, as readers were expected to be proficient dancers, so some instructions are ambiguous to the modern reader. The music, always a single line rather than a complete arrangement, contains some errors. As we will see below, this can lead to more than one credible interpretation of a dance and its music.

(The art of dancing & choreography), c. 1450.

As well as choreography, in De arte saltandi & choreas ducendi Domenico explains his philosophy of dance in the renaissance writing style, in which an activity must be underpinned with justifying principles and, often, classical references. Underlying Domenico’s choreography is a sense of control, order and decorum. He explains that the components of dance combine to make as refined a demonstration of intellect and effort as can be found anywhere.

These elements consist of:

Measure: understanding the music’s tempo and moving the body in time.

Memory: memorising the steps, their order and timing, and how they fit the music.

Agility and manner: “with smoothness, appear like a gondola that is propelled by two oars through waves when the sea is calm as it normally is. The said waves rise with slowness and fall with quickness.”

Measuring the ground: maintaining poise and a connection with the ground as you move.

Physical fluidity: “at each tempo one appears to … be of stone in one instant, then, in another instant, take flight like a falcon driven by hunger.”

After 16 chapters describing the aspirations of a refined dancer, 18 balli (singular: ballo) are described, complete with Domenico’s music, and 5 bassadanze, none with music. The ballo in the 15th century was a complex dance, any example of which combined steps from 4 different dance types in different metres:

bassadanza – compound duple time (modern 6/4), slow;

quaternaria – quadruple metre (modern 4/4), moderate speed;

saltarello – usually simple triple time (modern 3/4) or compound duple time (modern 6/8), quite quick;

piva – simple duple time (modern 2/4), fast.

The bassadanza was a slow, semi-processional dance which originated in Italy, popular in central Europe from the 14th century to the second half of the 16th century. It often had forward and backward movements and consisted of a combination of 8 types of step, danced close to the ground, without jumps or leaps. The music for the bassadanza – missing in Domenico’s book – usually consists in 15th century sources of the tenor only, long notes over which another musician would improvise a melody. If playing an instrument capable of two-handed polyphony, such as a harp or lute, a single musician could play the tenor and improvised melody.

Example: La giloxia

In modern commentaries, Domenico’s La giloxia is often given its spelling in other contemporaneous dancing masters’ manuscripts, gelosia, since this is also the modern spelling. In English, La giloxia / gelosia is The jealousy. It is one of the more straightforward balli in De arte saltandi in terms of its instructions, but both the music and the choreography still leave the modern musician or dancer with problems of interpretation.

First the music. When Paul Baker and I were asked to provide some period appropriate music for the TV series, The White Princess, about the marriage of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York (more about the issues of such historical programmes and films here), we decided to find some music new to us. We found Domenico’s La giloxia, c. 1450. Antonio Cornazano mentions it in passing in his work of 1455, but considers it too well-known to be worth describing. Nevertheless, it is included in full by Guglielmo Ebreo, 1463, and again when he writes as Giovanni Ambrosio, c. 1470. Guglielmo Ebreo’s work of 1463 was still being copied late in the 15th century, so it can be included in the date range of the Henry/Elizabeth story, set in the 1480s.

Libro dell’arte del danzare (Book of the art of dancing), 1455, and right are two pages of

Guglielmo Ebreo’s De pratica seu arte tripudii (On the practice or art of dancing), 1463.

The first makes reference to La gelosia, the second includes its music and choreography.

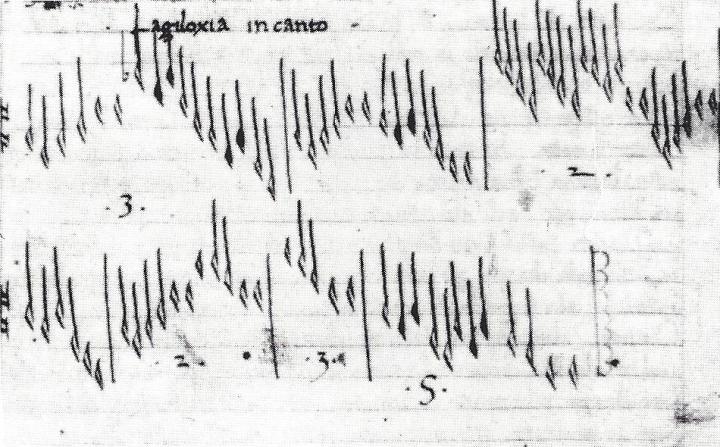

We set to work on decoding the music which, in the original, looks like this:

Taken literally, it looks like this in modern notation …

… and sounds like this.

The only ambiguous part is the number of times to repeat the last section. The music indicates “5”, but a literal interpretation of the choreography suggests twice. This is discussed below.

While the notes and rhythm of the music are unambiguous, they aren’t correct, as the high F flat in the first section and the repeated odd-sounding low F naturals at cadences show. I puzzled over it and sent Paul six different hypothetical versions of corrected music, including one treating the C clef as mistaken and interpreting it as an F clef. My six hypothetical corrections were clearly and audibly variations of wrongness. Paul suggested treating the F flat as naturalising, i.e. lower Fs are sharp and higher Fs with flats are natural, and we agreed that this worked best, but still the last section was clearly in error. Paul went with what his ears told him and interpreted the last 2 bars as being written 1 note too low. This resolved the music for us and is what you hear in the video. Of course, other solutions are possible.

La giloxia is one of Domenica’s playful dances we may characterise as narrative, expressing a mini-drama. The choreography sets up an interplay between male and female dancers by the means of a male dancer supplanting another and dancing with his partner, hence the title, The jealosy. Progression in the dance is achieved by performing it three times so that each man returns to dance with his original partner.

Domenico’s dance instructions (here leaving out some of the details about footwork for simplicity) will now be explored in relation to the two performances in the video by Saltus Gladii of Lithuania and Soubor Anello (Ensemble Anello) of the Czech Republic. They were the best and most clear examples I could find of performances which accurately reflect Domenico’s instructions and illustrate credible differences of interpretation.

(a) Domenico stipulates that the dance begins with three male/female couples, one behind the other, dancing six slow saltarelli in quadruple metre. Having danced six, there is still some music left. A remarkable six handwritten copies of Guglielmo Ebreo’s dance manual survive, all including La giloxia as gelosia, as well as one copy of his dance manuscript under his baptised name, Giovanni Ambrosio. Of these seven copies, three agree with Domenico that there are six slow saltarelli in the first section of music, but four copies state eight saltarelli, which fills the time allowed in the music. Both Saltus Gladii and Soubor Anello perform eight saltarelli, matching the music.

(b) The man in front leaves his lady, passing in front of her dancing three doubles. He then touches the hand of the middle lady with the reverence on the left foot, as we see.

(c) The middle man dances one saltarello in quadruple metre to be next to the first lady.

(d) The man now in the middle leaves his lady, passing in front of her dancing three doubles. He then touches the hand of the rear lady with the reverence on the left foot.

(e) The rear man dances one saltarello in quadruple metre to be next to the middle lady.

(f) All move forward with eight pivas.

(g) The first man and first lady half-turn to face each other, followed by the second then the third couple. In the video, both Saltus Gladii and Soubor Anello make this a 360 degree turn.

(h) Domenico’s choreography and music appear to be at odds here, with the choreography apparently requiring the last section of music to be played twice while the music states five times. The “5” on the music may simply be a mistake, but we have no way of knowing, so Saltus Gladii’s and Soubor Anello’s different ways of resolving the discrepancy have equal validity. Domenico’s instructions state that the man and woman of each couple now face each other: each couple take right hands and take three simple steps to change places. They then take left hands and take three simple steps to return to their places. If each couple do this simultaneously, this requires the final section of music to be played twice, as Domenico’s choreography appears to imply, and this is the option Soubor Anello take. Saltus Gladii dance the last section five times through, as the music states. They do this by each couple taking the first three steps to change places in succession, making three times through, each couple take the next three steps to change places simultaneously, making four times through, and they end with a reverence (as all dances of the period do when complete) to make five times through.

Domenico’s legacy and influence

Domenico da Piacenza has a special place in dance and music history since his De arte saltandi & choreas ducendi is the first surviving written record of clear and detailed choreography, with all the balli complete with music. This alone would be enough to mark him out as important; but his significance and skill were well-recognised within his own lifetime, inspiring imitators whose credibility as dancing masters was enhanced by association with his name.

Domenico’s hand-copied dance treatise inspired others to follow in his dance steps with their own manuals, a trend which continued into the 16th and 17th centuries when mass-produced prints became viable for dancing masters. As well as being a skilled dancer, a sought-after choreographer of social dances and therefore no doubt a teacher able to communicate and enthuse, he was born into the right class at the right time to be able to ride the wave of the self-consciously elite cultural activity of the renaissance, funded by Italy’s most powerful families, copied by the Italian middle class, then reproduced across Europe as other countries imitated Italy’s self-styled rebirth.

Bibliography

Chiappini, Luciano (1998) House of Este. Available online here.

Kendall, Yvonne (2007) Early Renaissance Dance, 1450-1520. In: Kite-Powell, Jeffery (ed.) A Performers’ Guide to Renaissance Music. Second edition. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indianapolis University Press.

Lockwood, Lewis (2009) Music in Renaissance Ferrara 1400-1505: The Creation of a Musical Center in the Fifteenth Century. New York: Oxford University Press.

Smith, A. William (1995) Fifteenth-Century Dance and Music. Twelve Transcribed Italian Treatises and Collections in the Domenico Piacenza Tradition. Volume I: Treatises and Music. Hillsdale, New York: Pendragon Press.

Sparti, Barbara (1986) The 15th-century balli tunes: a new look. Early Music. Vol. 14, No. 3. (August 1986). pp. 346-357.

Spedding, Chloe (2013) Issues of Dance Notation: Domenico da Piacenza’s Dance Writing in Fifteenth-Century Italy. A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Italian. Victoria University of Wellington 2013. Available online here.

Stephens, Vivian and Cellio, Monica (1997) Joy and Jealousy. Available online here.

Wilson, David R. (1992) ‘La giloxia’/’Gelosia’ as described by Domenico and Guglielmo. Historical Dance. Volume 3, Number 1. pp. 3-9. Available online here.

© Ian Pittaway. Not to be reproduced in any form without permission. All rights reserved.

My brother Robert Mullally, author of books on the carole and the basse danse, was completing a book on Domenico da Piacenza when he died earlier this year. Do you know anyone who might be interested in taking over his work?

Hello, Evelyn.

Thank you for your post, and I’d like to express my sadness over the death of your brother. Robert’s book on the carole is the best and most comprehensive survey and analysis I’ve seen. I don’t know anyone personally who would continue his work on Domenico da Piacenza, but I do have leads to follow. I will email privately.

With my best wishes.

Ian

Hello

Would it be ok for me to use your modern notation tune – with some adaptation – for the recorder group I play with. We are playing an ‘Italian’ programme at the moment and already have an arrangement of amoroso which would probably work well coupled with La giloxia.

We would be playing at NT and EH properties. We are an amateur group not professional.

Thank you

Yes, of course, Mary, and thank you for asking. Be sure to play the corrected version, as described underneath the modern notation and as heard in the video, rather than the literally transcribed and clearly uncorrected notation.

I hope it goes well.

All the best.

Ian

Thank you Ian.

That’s really helpful.

We are hopefully playing them this weekend and next and then later in the summer.

Mary