Alliteration was a foundational feature of medieval verse. Animals playing musical instruments are regularly seen in medieval art. The 14th century stone-carved musicians of Saint Mary’s Church, Cogges, Oxfordshire, delightfully bring these two elements together: there are nine instruments played by eight alliterative animals (one plays two), including a sheep playing a citole and a boar playing a bagpipe (above).

This article begins with examples of alliteration in medieval poetry (Beowulf, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Piers Plowman), songs (Foweles in þe frith, Doll thi ale), and the medieval mystery plays; followed by illustrations of animals playing music in medieval and renaissance art. That is the background for a brief history of Saint Mary’s Church, Cogges, and an explanation of its eight alliterative animals playing medieval music, with photographs of every carving and a video of each instrument being played.

Alliteration in medieval and renaissance literature

First to state our linguistic terms. Old English, the earliest form of the English language, was used in Anglo-Saxon England from c. AD 450. This form of English continued until c. 1150, nearly a century after the Norman Conquest of 1066. Old English had transformed by c. 1150 into what is now known as Middle English, used until the late 15th century, followed by Early Modern or Tudor English.

Poetry in Old English was not based on rhyme schemes, but on alliteration, the repetition of sounds said in a succession of syllables. So foundational was this to Old English poetry that scholars of language and literature now call it Old English metre. Specifically, each line in Old English metre is in two halves; one or more syllable in the first half of the line alliterates with one or more syllable in the second half of the line.

The longest epic poem in Old English is the anonymous Beowulf, probably copied in the early 11th century. The poem relates the adventures of the eponymous hero, who fights a monster called Grendel, Grendel’s mother, and a dragon which guards treasure.

The first 8 lines are as follows, first in Old English, then in modern English, translated by Francis B. Gummere, retaining the alliteration. The alliterative sounds are highlighted in bold.

Hwæt. We Gardena in geardagum

þeod cyninga þrym gefrunon

hu ða æþelingas ellen fremedon

Oft Scyld Scefing sceaþena þreatum

monegum mægþum meodo setla ofteah

egsode eorlas syððan ærest wearð

fea sceaft funden he þæs frofre gebad

weox under wolcnum weorðmyndum þah

Lo, praise of the prowess of people-kings

of spear-armed Danes, in days long sped,

we have heard, and what honour the athelings [princes eligible for kingship] won.

Oft Scyld the Scefing from squadroned foes,

from many a tribe, the mead-bench tore,

awing the earls. Since erst he lay

friendless, a foundling, fate repaid him:

for he waxed under welkin [the vault of heaven], in wealth he throve

(As with all pictures, click to see larger in a new window, click in new window to further enlarge.)

Alliterative poetry continued in the Middle English period, as we see in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, an anonymous epic poem of the late 14th century. The story is that Gawain, a knight at King Arthur’s court, was attending a Christmas feast at Camelot when a knight with green skin and green hair, riding on a green horse, arrived to challenge the assembled knights to a game, which led to the trials and temptations of Gawain.

The first 4 lines will suffice to show the poem’s method, followed by the same in modern English by A. S. Kline, retaining the alliteration.

Siþen þe sege and þe assaut watz sesed at Troye,

Þe borȝ brittened and brent to brondeȝ and askez,

Þe tulk þat þe trammes of tresoun þer wroȝt

Watz tried for his tricherie, þe trewest on erthe:

Soon as the siege and assault had ceased at Troy,

the burg broken and burnt to brands and ashes,

the traitor who trammels of treason there wrought

was tried for his treachery, the truest [i.e. most treacherous] on earth.

The epic poem Piers Plowman was written alliteratively by William Langland in 1365–70 and 1390, a similar time to Sir Gawain. Below are lines 1-10 of the Prologue, first in Middle English, then in modern English by Ian Pittaway, retaining the alliteration.

it appears in the ‘B’ text, folio 1r of

Bodleian Library MS. Laud Misc. 581.

In a somer seson • whan soft was the sonne

I shope me in shroudes • as I a shep were

In habite as an heremite • unholy of workes

Went wyde in this worlde • wondres to here

Ac on a may morning • on malverne hulles

Me byfel a ferly • of fairy me thoughte

I was wery forwandred • and went me to reste

Under a broke banke • bi a bornes side

And as I lay and lened • and loked in the wateres

I slombred in a slepying • it sweyved so merye

In a summer season • when soft [mild] was the sun

I clad me in clothes • as I a sheep was

In a habit as a hermit • unholy of works

Went wide in this world • wonders to possess.

And on a May morning • on Malvern Hills

There befell on me a marvel • by magic I thought

I was weary of wandering • and went I to rest

Below a broad bank • by a brook side

And as I lay and leaned • and looked in the waters

I slumbered in sleeping • it swept [me away] so merry

There are further examples of alliteration in medieval song.

In the modern day, there is a clear distinction between a poem and a song lyric, not only in that lyrics are sung and poems are not, but in the level of linguistic sophistication, the complexity of the form. Compare, for example, part of Dylan Thomas’ poem, Do not go gentle into that good night, with part of Beyoncé’s lyric for her single, Virgo’s Groove.

Do not go gentle into that good night by Dylan Thomas

Do not go gentle into that good night by Dylan Thomas

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Though wise men at their end know dark is right,

Because their words had forked no lightning they

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Good men, the last wave by, crying how bright

Their frail deeds might have danced in a green bay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Virgo’s Groove, sung by Beyoncé, written by Beyoncé Knowles, Leven Kali, Solomon Cole, Daniel Memmi, Dustin Bowie, Darius Dixson, Jocelyn Donald, Jesse Wilson, Denisia Andrews, Brittany Coney.

Baby, come over (Ooh, yeah)

Baby, come over (Ooh)

Baby, come over (Baby, come over)

Come be alone with me tonight

All these emotions (All these emotions)

It’s washin’ over me tonight, ah

Right here, right now

Iced up, bite down

Baby, lock in right now

I want it right here, right now

Cuddled up on the couch

Motorboat, baby, spin around

Slow-mo comin’ out my blouse

I want it right here, right now

Putting aside the question of how it took ten people to come up with that, it is clear that a song lyric of this kind requires no work from the listener, no contemplation or depth of understanding, as opposed to good poetry, which requires all of that. In the medieval period there was no distinction between a verse for a poem or for a song: both required from the writer a high level of skill, linguistic complexity and dexterity, and therefore focus from the listener. In the medieval period, a song was sung poetry.

We see this in the anonymous and beautifully alliterative song Foweles in þe frith from c. 1270, a century before Sir Gawain and Piers Plowman. Only the first verse survives. (In this example, alliterating in modern English proved impossible, so only the alliterative sounds of the Middle English verse are highlighted.)

Foweles in þe frith •

þe fisses in þe flod •

And I mon waxe wod •

sulch sorw I walke with

for beste of bon and blod •

Birds in the wood

the fish in the flowing water

And I mourn, grow mad

such sorrow I walk with ~ or ~ I journey through life in sorrow ~ or ~ such sorrow I stay awake with

for the best living person ~ or ~ for a living animal/beast

As we see hinted from the modern English translation, even that one verse of Foweles in þe frith is complex enough to require a whole explanatory article, which can be accessed by clicking here, with a video of the song being performed.

In the song, Doll thi ale, a warning against alcoholic drink, in which to doll your ale is to dullen it, to water it down, there is a different schematic use of alliteration, used to drive home the repeated message, as we see below from the burden (refrain) followed by the first 2 verses. As with Foweles in þe frith, this song has a rhyme scheme as well as alliteration. The source is dated c. 1460–90, Bodleian Library MS. Eng. Poet. e. 1., a manuscript with 76 songs, only 2 complete with music, and 2 short poems. Unfortunately, Doll thi ale is not one of those with music.

Doll thi ale, dol, dol thi ale, dole,

Ale mak many a mane to have a doty poll [stupid head].

Ale mak many a mane to styk at a brere [briar]

Ale mak many a mane to ly in the myere [mire]

And ale mak many a mane to slep by the fyere [fire]

With doll.

Ale mak many a mane to stombyl at a stone

Ale mak many a mane to go dronken home

And ale mak many a mane to brek hys tone [toe]

With doll.

Another schematic but in this case occasional use of alliteration within a rhyme scheme is used in the surviving texts of the medieval mystery and miracle plays. Medieval guilds performed miracle plays about the lives of saints, and mystery plays, vernacular Biblical dramas which told the whole story of Christian redemption from the creation to the flood to Christ’s birth, death and resurrection, ending with the Final Judgement. This was people’s theatre, the texts full of down-to-earth language, humour and pathos.

Most major towns had a unique cycle of mystery plays, though not all would be performed in a particular year. Lack of evidence prevents knowledge of how far back the tradition goes, but it is clear that from 1210 the municipal authorities had taken over the general running of the mysteries. When the Festival of Corpus Christi was fixed in the liturgical calendar in 1311, mystery plays became associated with this annual celebration, a movable feast between late May and mid June.

In the 16th century, under King Edward VI and Queen Elizabeth I, miracle and mystery plays were threatened, revived, then ultimately suppressed for their association with the old Catholic faith. One of the Coventry texts and the five Chester texts were written in the late 16th or early 17th century, well after the plays could ever have been performed. Clearly there were people eager to remember and document a long and well-loved tradition, to prevent it fading forever from memory.

from a cycle performed in York Minster in 2016.

Above: Lucifer and the rebel angels are cast out of heaven.

Below: Christ’s entry into Jerusalem.

Photographs by Anthony Chappel-Ross, from Heather Cawte (2016) – see bibliography.

(As with all pictures, click to see larger in a new window, click in new window to further enlarge.)

There follows three typical examples of the use of alliteration in mystery plays (with spelling modernised by A. C. Cawley, 1977).

The Fall of Man, Scene I, from the York Pageant of the Coopers, text dated 1463–77.

Satan: For woe my wit is in a were [confusion]

That moves me mickle [much or greatly] in my mind:

The Godhead that I saw so clear

And perceived that he should take kind [take a form in accordance with nature]

Abraham and Isaac, Scene IV, The Brome Manuscript, late 15th century

Doctor: Lo, sovereigns and sirs, now have we showed

This solemn story to great and small.

It is good learning to learned and lewd [unlettered, without formal education]

And the wisest of us all

The Harrowing of Hell, Scene I, from the Chester Pageant of the Cooks and Innkeepers, 5 copies of the text from the late 16th and early 17th century

Adam: Ah, Lord and sovereign Saviour

Our comfort and our counsellor

Of this light thou art author

As I see well in sight.

This is a sign thou wouldst succour

Thy folk that be in great languor [distress]

And of the devil be conqueror

As thou has yore behight [long ago promised].

In these plays, alliteration is not in use most of time, so its presence is significant for its location in the drama. Alliteration creates momentum, and it only appears briefly at the opening of a scene or when a new character talks for the first time, a literary device to add a push to proceedings, a temporary emphasis, an aural forward motion.

Medieval and renaissance musical animals

Having established a solid medieval and renaissance tradition of literary alliteration, we now ask: what is the pedigree of medieval musical animals?

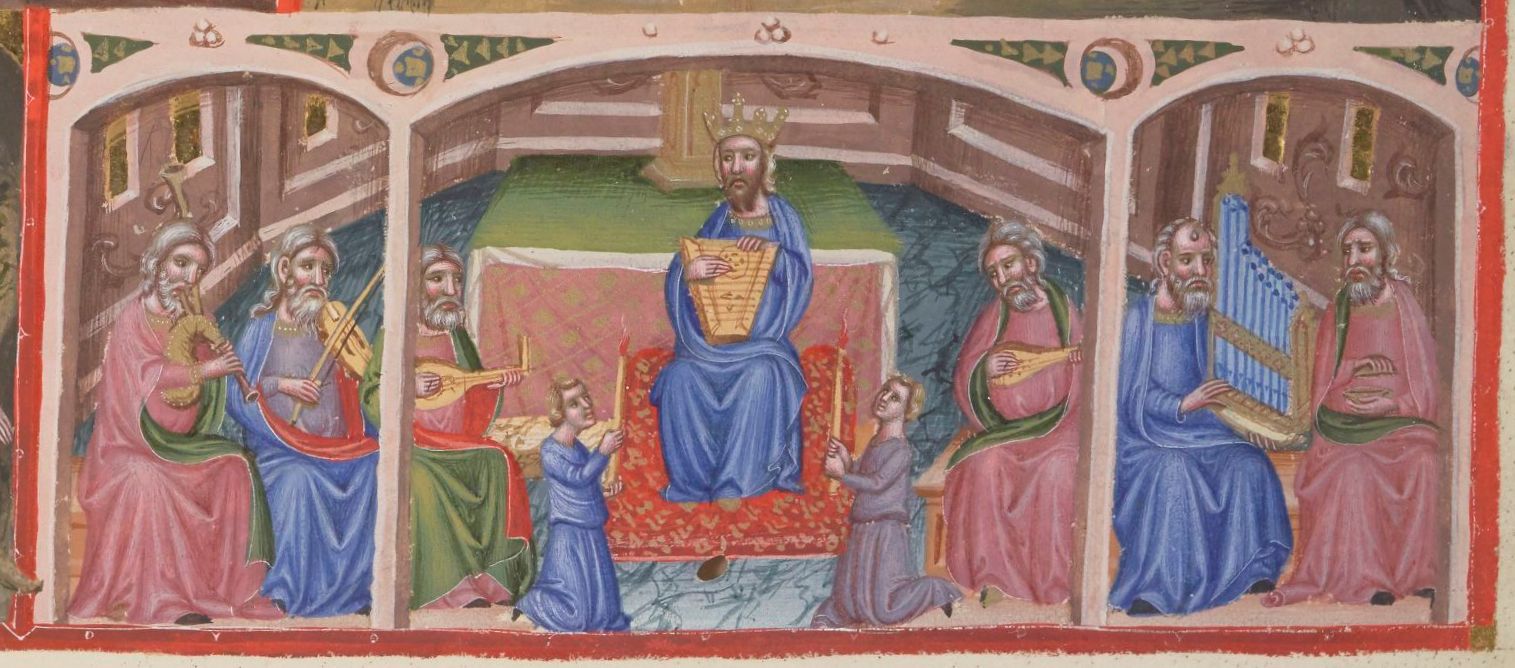

Medieval manuscripts regularly show fantastical hybrids of human and animal, or a hybrid of different non-human animals, playing music. We see two examples above playing citole and bagpipe, details below, in the Anglo-Norman Howard Psalter (British Library Arundel MS 83, folio 33v), c. 1308–c. 1340.

Hybrids aside, there are myriad examples of medieval music-making mammals.

A hare (rabbit?) plays a shawm and an ape plays a shawm and tabor (rather than pipe and tabor), apparently trying to disturb the lovers between them (MS. Bodl. 264, 1338–1410).

A rabbit (hare?) plays a positive organ while a dog works the bellows (Macclesfield Psalter, c. 1330–40).

A cat plays fiddle and a pig a portative organ (British Library Harley 6563, c. 1320–30).

In a series of bas-de-page scenes depicting the funeral of Reynard the fox (the use of Reynard in iconography is described in this article), animals play musical instruments (Walters Ms. W.102, c. 1300): a sheep rings bells; a horse plays pipe and tabor; …

… an ass plays a mute cornett (straight cornett) and bell; a dog plays bagpipes; …

… a cat beats a drum; and a bear plays a cornett (of the usual curved shape).

We see the same phenomenon in renaissance art.

A bear plays lute for an owl singing, while a wolf stalks a rabbit (Breviarium abbatis pars hiemalis – The abbot’s winter breviary, Salem, Germany, 1493–94).

An ape plays vielle (Prayer Book of Charles the Bold, 1469–90) and another a bagpipe (Breviary of Queen Isabella of Castille, c. 1497).

Ms. 37, folio 41v, Flanders, 1469, c. 1471, and c. 1480–90.

Right: British Museum, Breviary of Queen Isabella of Castille, Additional 18851, Netherlands, c. 1497.

A bear plays a viol and a boar sings, with a shawm on the ground between them. This is in the second volume of a two part Gradual (liturgical book of chants), produced 1507 and 1510, colloquially named The Geese Book, at the foot of a page with the music for the Introitus: Confessio et pulchritudo in conspectu eius, for the Mass of Saint Lawrence, which can be heard here (a brief 1:46).

volume 2, produced in Nuremberg in 1510.

Left: the whole of folio 88r, with the music for Confessio et pulchritudo in conspectu eius.

Right: the detail of the musical bear and boar.

This is a tiny taste of the animal iconography available for medieval musical mammals and for renaissance representations of creative creatures making music. And we have only looked at manuscripts: many more can be found in ecclesiastical carvings.

For our purpose, the striking thing about these animals playing instruments is how unalliterative they are. No matter how hard one tries, one cannot make a hare or rabbit playing a shawm alliterative, or an ape playing a bagpipe, or a bear playing a lute. The one exception here is the pig playing a portative organ, but that alliteration, not being part of an overall schema, appears to be incidental.

The striking thing about the musical animals in Saint Mary’s, Cogges, is that the alliteration is immediately obvious. And so we turn to the church and its mammalian musical monuments.

Saint Mary’s, Cogges

Saint Mary’s Church, Cogges, Witney, Oxfordshire, was built in the 12th century, originally as a two cell structure in the late Saxon style. It was probably associated with the priory, which is now the vicarage.

Photograph © Ian Pittaway.

(As with all pictures, click to see larger in a new window, click in new window to further enlarge.)

Photograph © Ian Pittaway.

The west end of the church, now part of the chancel (area around the altar), is probably early Norman. The main body of the chancel and the nave (central area from the entrance to the chancel) dates from the late 12th and early 13th century. In the 14th century, 1330–40, there was major building work funded by the de Grey family, who held the manor (i.e. owned the land) of Cogges. It was then that the north aisle and Blake Chapel were added, where we find the mammalian musical corbels (projections from the face of a wall). Three are on the internal north wall in the north aisle, one on the opposite wall of the aisle, and four more on the north wall in the Blake Chapel just beyond.

Photograph © Ian Pittaway.

corbels just visible spaced along the top of the left wall.

Photograph © Ian Pittaway.

four musical corbels just visible through the arches.

Photograph © Ian Pittaway.

In the 16th and 17th century, many churches in newly-Protestant England – and around Europe – were physically attacked by Puritans to destroy their ‘Catholic idolatry’, with invaluable medieval iconography irreparably vandalised or destroyed. In Beverley Minster, a church in Yorkshire, extensive work was carried out in the late 19th and early 20th century to restore and make replacement parts for their damaged 14th century minstrels (which you can read about here). Most churches have not attempted this considerable restoration work. Thankfully some churches, like Saint Mary’s, Cogges, have not needed to, as they escaped the hammers of the iconoclasts.

Saint Mary’s Church is now a Grade I listed building.

Alliterative animals making medieval music in Saint Mary’s

I knew of and wanted to visit Saint Mary’s, Cogges, because of its appearance in Jeremy and Gwen Montagu’s book, Minstrels & Angels, a compendium of the musical iconography to be seen in English medieval churches. As the Montagus list it, the carvings in the church consist of: “man blowing a horn from the corner of his mouth, sheep playing citole, minstrel with bells on his wrists playing double duct flute, monkey playing a harp, goat playing a fiddle, pig with psaltery on knees, ?dog with bagpipe left pawed, rabbit with pipe and tabor”.

This description gives no hint of an alliterative element, and the book’s list of animals wasn’t always what I saw with my own eyes. The original 14th century paint has completely gone, and the carver changed the features of some animals to make them more humanoid. These two factors mean that in some cases it isn’t easy to discern which animal is being depicted, as we will see.

Before taking photographs, I wanted to see all eight figures, and within minutes I realised I was seeing alliteration: a sheep plays a citole, a sheep plays a psaltery, a simia (ape) plays a cithara (harp), a hunter blows a horn, and a boar plays a bagpipe. That’s five of the eight. The other three I couldn’t immediately work out alliteratively: a man plays double flute and bells, a rabbit or hare plays pipe and tabor, and a goat plays a vielle (medieval fiddle).

I had previously seen a visual play on alliteration in the aforementioned Beverley Minster: a misericord of 1520 (below) shows pigs with, from left to right, a saddle, a bagpipe, and a harp. Given the variety of words in English for a pig, this clearly suggests a sow wearing a saddle, a boar playing a bagpipe (or a pig playing a pipe), and a hog playing a harp.

(As with all pictures, click to see larger in a new window, click in new window to further enlarge.)

The very nature of the imagery on misericords – and medieval/renaissance art generally – is designed for the viewer to make associations. In Beverley Minster, for example, we have a misericord carving of a pelican piercing its own breast to feed its young, a symbol of Christ’s sacrifice as described in the bestiaries; we have a carving of foliage, a typically medieval reminder of the brevity of fecundity and the shortness of life itself; and so on. Therefore alliterative word-play is not only obvious from the image above, it is just the sort of idea we would expect in medieval and renaissance art, which intends the viewer to engage with the world of ideas associated with the portrayal.

Given the pairings of animals with instruments in Saint Mary’s, it didn’t seem possible to me that five of the eight figures were not intentionally alliterative when it was immediately obvious, nor that five out of eight were alliterative and the remaining three were not. The fact that there are two sheep, one playing citole, the other a psaltery, rather than eight different animal types, is best be explained by the carver’s desire to alliterate players with their instruments.

I had immediately spotted five alliterative pairings of player and instrument, four in Middle English and one in Latin. Perhaps there were other Middle English or Latin names for the remaining three animals and/or their instruments that I hadn’t yet brought to mind.

I couldn’t work it out, so I posted pictures on social media and asked for suggestions. The people mentioned in the following discussion are those who made valuable contributions and suggestions. A name in blue is a link to that person’s website.

We will work from right to left from the far end of the Blake Chapel to the beginning of the north aisle.

citole

(As with all pictures, click to see larger in a new window, click in new window to further enlarge.)

From the Middle English, a shẹ̄p (sheep) plays a citōle (cithole, sitole, citule, citola, sitol, cetoyle, sital, cistole, citolent, chytole, standardised modern English: citole).

The shape of the sheep’s face has been changed to make it more humanoid, with a more pronounced and separated nose than a sheep has, and the front legs have become arms, the sheep’s two toes turned into four fingers.

The citole is shown in the typical wedge shape, widest front to back at the peg end and narrowest at the trefoil, with three courses of strings, and it has two sound holes either side of the string band rather than a central rose, all within the broad range of expectations for the instrument.

To see and hear Ian Pittaway playing citole, La septime estampie Real (The seventh Royal estampie), c. 1300, click the picture below.

To learn more about the citole, click here and here.

harp

From the Latin, a simia or simius (ape, monkey) plays a cithara (harp).

The simian is shown realistically in that the artist carved an enlarged bottom, seen on the female of the baboon and macaque; but unrealistically in that she has a shorter and more upright or flat face to make her appear more humanoid.

The Greek kithára (κιθάρα), Assyrian chetarah, and Latin cithara, were names for a lyre for which there is evidence dating back to 1700 BCE. In ancient usage, the word came to be used for any plucked stringed instrument and, in the medieval period, the word naturally transferred from the lyre to the harp specifically, as well as being used as a general term for a stringed instrument to conform to ancient Greek and Roman usage.

The harp is shown with eight strings, a reduction in number used by carvers of harps and other instruments with a relatively large number of strings (as this article explains).

To see and hear Ian Pittaway playing harp, La Sexte estampie Real (The Sixth Royal estampie), c. 1300, click the picture below.

To learn more about the medieval harp, click here, here and here.

psaltery

(As with all pictures, click to see larger in a new window, click in new window to further enlarge.)

From the Middle English, a shẹ̄p (sheep) plays a sautrīe (sautrī, sautriȝe, sautrẹ̄, sautrei, sauterie, sauteri, saltre, psautrie, psautri, psautrẹ̄, psauteri, modern English: psaltery).

As with the sheep playing citole, the shape of the face has been changed to have a more pronounced and separated nose, and the front legs have become arms, the sheep’s two toes turned into three fingeresque digits to make it more humanoid. The carved shape of wool on the sheep playing the citole remains visible and obvious; on the psaltery player the carved wool has worn considerably, but remains of the wool pattern on the chest and the wool ‘cap’ on the head confirms the animal’s identity.

Only the underside and sides of the psaltery can be seen, since the instrument is played flat on the lap and viewed from below. The playing position on the lap is seen occasionally in medieval iconography, but the more usual position was against the player’s chest, facing forward, as we see demonstrated by Andrew Lawrence-King below. To see and hear Andrew playing psaltery, Rosa das rosas, c. 1257–83; Quant ai lo mon consirat, 13th century; and Cristoforo Malvezzi, Coppia gentil, 1589, click the picture below.

To read more about the psaltery, click here.

double duct flutes and bells

And so we come to the first figure for which alliteration isn’t obvious. In the corner of the Blake Chapel we see a man playing two wind instruments, with a bell attached to each wrist.

This player’s instruments are duct flutes rather than recorders. The recorder is a complex type of flute with an internal duct, a fixed windway formed by a wooden plug or block, distinguished visually from other internal duct flutes by having seven finger holes on top and a single hole at the back for the thumb of the upper hand. The first recorders appeared in iconography in the second decade of the 14th century, slightly before the Cogges carvings of 1330–40, and the first use of the name, “Recordour”, refers to the playing of the Earl of Derby in 1388, before he became King Henry IV. The type of mouth-blown instrument more simple than a recorder is referred to as a pipe, flageolet or duct flute, and this is what we see in Cogges. The fact that the only finger holes are on the end of each flute makes them tabor pipes, with two front holes on the bottom end and a third hole at the back. Such pipes are usually played with one hand while the other plays the tabor or drum (a combination of instruments we will see below), so a skilled player could easily play two one-handed pipes at once.

As shown below, geminate or double instruments are not unusual in medieval iconography.

Left: double duct flutes in a fresco by Simone Martini, Italy, 1312–18, Saint Martin is knighted.

Centre left: double duct flutes from folio 87v of The Luttrell Psalter

(British Library Add MS 42130), England, c. 1325–40.

Centre right: double shawms from folio 174r of The Luttrell Psalter.

Right: double trumpets from folio 126r of The Queen Mary Psalter

(British Library Royal 2 B VII), England, 1310–20.

The Cogges player has two notable features.

The first is the bells on the wrist, which could be rhythmically activated by co-ordinated movements of the head and arms while the player blows the flutes. I know of no other examples of this method of playing in medieval (or any other) iconography. There are, however, some rare instances of pipe and bell, played one in each hand, as we see below.

Right: David the shepherd, yet to become king, with pipe and bell, in the Maciejowski Bible, also called

the Crusader Bible, Paris, 1240s (Morgan Library & Museum, New York, Ms M.638, folio 25v).

(As with all pictures, click to see larger in a new window, click in new window to further enlarge.)

The second feature was raised as a comment by John Mallett (medieval bagpipes, trumpet, fiddle and duct flute; vielle a rue) on my social media post to seek answers for the three figures that are more difficult to alliterate: John noticed that the flutes are not tubular on the outside, but have four well-defined corners. David Badagnani (oboe, English horn, fiddle, banjo, accordion, piano, viola da gamba, guitar, shawm, recorder, doedelzak, Scottish smallpipes, sheng, suona, houguan, xun, erhu, gaohu, yehu, zhonghu, banhu, sihu, dahu, yueqin, zhongruan) pointed out that the pibgorn in the video below has square corners like the Cogges pipes.

This is an identical design to some medieval bagpipes (and some modern Swedish and French bagpipes), which have a rectangular chanter and stepped finger holes. Two examples are shown below.

in the arcades of Beverley Minster, Yorkshire, England.

To read more about the carvings of Beverley Minster, click here.

Photographs © Ian Pittaway.

Below: Two views of a bagpipe played by a life-size figure in the Musée Saint-Rémi,

Reims, France, 13th century, with a rectangular chanter and stepped finger holes.

(As with all pictures, click to see a larger view in a new window.)

It is not possible to tell whether the tabor pipes played by the Cogges musician have the stepped finger holes of the bagpipes and pibgorn, as the fingers completely cover the ends of the pipes, but they do have a rectangular shape and corners. The squared externals make an aesthetic difference, and the steps may help the player’s finger placement, but it doesn’t change the shape of the bore, which must always be circular, as we see from the carving of the Beverley Minster bagpiper viewed from below.

What could be the alliterative description be? The common word for a paid entertainer, minstrel (minstralle, minstral, minestral, etc.) doesn’t seem to suggest anything, but the alternative word pleiere (player, entertainer, minstrel) suggests pleiere with pīpes and belles.

To see and hear Pierre Hamon play Puis que ma dolour by Guillaume de Machaut (1300–77) on double duct flute, click the picture below.

horn

Moving now out of the Blake Chapel, to an arch opposite the north wall, we see a figure that can be described in modern English just as in Middle English: a hunter blows a horn.

This is not the modern hunting bugle, made of brass, but an animal horn used for blowing. As a musical instrument it is perfunctory, playing a maximum of three pitches. Its function is aural signalling rather than aesthetic pleasure, different blowing patterns used to signal, for example, the direction of the quarry and the successful death of the animal.

To see Corwen ap Broch demonstrate blowing horns, click on the picture below.

To learn more about the various forms of musical horn, click here and go to the subheading, The reredos.

pipe and tabor

Opposite the hunter blowing a horn is the first of three musical animals on the wall of the north aisle. This figure is described in Minstrels & Angels by Jeremy and Gwen Montagu as “rabbit with pipe and tabor”. It doesn’t look quite as we’d expect for a rabbit, or perhaps a hare, but not for the reason of making the animal more human-like, as above: the ears are too small for either a rabbit or a hare. Kathryn Wheeler (medieval fiddle, pipe and tabor, recorders, concertina), unconvinced by the rabbit identification, thought at first sight it was a dog or a bear; and Julia Zimina (gittern, lute, vihuela, baroque guitar, baroque and modern mandolin) thought it a dog or a bat.

This is the one we had most trouble identifying and alliterating. For me, the bend of the legs and the elongated toes rule out a dog or a bear, but Julia’s suggestion of a bat seemed a possible breakthrough. There are no visible wings: would carving wings detract from the details of the instruments, or is this not a bat? Jude Rees (bagpipes, shawms, crumhorns, curtal, rauschpfeife, recorders, pipe and tabor, oboe, saxophone, hurdy gurdy) suggested a pipistrelle with a pipe and tabor, which I thought a wonderful suggestion but, unfortunately, pipistrelle was not defined as a bat species until 1774.

For the animal, I think the realistic possibilities, given the features of the face, the length of the ears, the angle of the legs and the length of the toes, are: a bat, though we have to account for the lack of wings: a mouse; or a rat. This leads us to two alliterative alternatives.

The first is Middle English, a bakke (bat) with a bēter (beater for a drum).

The second suggestion is, I think, more likely: Latin pestis, or Middle English pestilence, playing pīpe and tā̆bǒur. I do not mean pestilence as in the bubonic plague, what was later called The Black Death, which spread around Europe in 1348-9 and killed around 25 million people, up to a quarter of Europe’s population, as this was slightly after the making of these carvings for the church in 1330-40; nor therefore do I mean the association of rats with the spread of the plague, a modern idea not present in the 14th century which has proven incorrect: it was humans, not rodents, who carried the fleas and lice which spread the plague. I simply mean mice or rats were called pestilens (pestelence, pestilence, etc.) in the ordinary sense of a pestilens of bestes, i.e. an infestation, as rodents were a common pest that ate stored food by humans.

To see Aahmes Quince play pipe and tabor, Qui que face a ce rotruenge nouvele by Gautier de Coincy, from Miracles of Notre-Dame, early 13th century, click on the picture below.

To learn more about pipe and tabor, click here and go the heading, pipe and tabor.

fiddle or vielle

The identification of the next figure is obvious: a ram with a fiddle. As on previous sheep figures, the nose has been made more pronounced to make the face appear more humanoid, and the same in this case has been done to the teeth.

The word for rām is the same in Middle as in modern English, with some minor Middle English variants: rame, ramme, rom, rem. The variants of fiddle were many: fidel, fidle, fedle, fedele, fithele, fethele, phethele, phetele, fieþle, fidula, viþele, videle, vielle, viella, viola, viula, viuela, vihuela.

None of these words produce alliteration. There is, however, an easy to route to find it in Middle English using alternative names for the animal with the implement used to produce notes: a blēt (sheep) with a boue (bow), or more likely a bukke (buck, adult male sheep, i.e. a ram) with a boue (bow).

To hear Kathryn Wheeler playing a Salterello from c. 1400 on medieval fiddle, click on the picture below.

To learn more about the medieval fiddle, click here.

bagpipe

play the video.

Our final musical mammal in Saint Mary’s, Cogges, is of course a bōr (boar) playing a bagge-pīpe, or a pigge playing a pīpe (pipe being a common abbreviation of bagpipe).

As on previous figures, the animal has been humanised: the pig snout has become a broad nose; the lips are filled out around the bagpipe mouthpiece; the front legs have become arms and the cloven trotters have been turned to fingers.

There were various types of medieval bagpipe: the one in Cogges has a flat-face chanter with stepped finger-holes, as shown above on the pibgorn and on the Beverley Minster and Musée Saint-Rémi bagpipes, and a single drone pipe. To see and hear Paul Martin (playing renaissance music) on a single drone bagpipe with a rounded chanter, click on the picture on the right.

To read about the variety of medieval bagpipe forms, click here and go to the subheading, bagpipes.

Conclusion about Cogges and the musical mammals

In conclusion, I have demonstrated that:

• alliteration was a fundamental feature of medieval poetry;

• being sung poetry, medieval song words were part of the alliterative schema;

• alliteration also appeared in a less thorough-going way in renaissance literature.

I have further shown that:

• musical animals were commonplace in medieval and renaissance art;

• there was no general schema for which animal was shown playing which instrument.

These two themes of alliteration and musical animals come together in the 14th century church of Saint Mary, Cogges, in the following way.

• Alliteration in five out of the eight musical figures is obvious and striking, and therefore cannot be accidental. We do not have random animals coupled with instruments – such as a cow with a psaltery, a horse with a citole and a dog with a bagpipe – we have clearly alliterative combinations:

1. a shẹ̄p plays a citōle

2. a simia plays a cithara

3. a shẹ̄p plays a sautrīe

4. a hunter blows a horn

5. a bōr plays a bagge-pīpe or a pigge plays a pīpe

• Alliteration in the remaining three figures is less immediately obvious and is likely to be:

6. pleiere with pīpes and belles

7. pestis playing pīpe and tā̆bǒur

8. bukke with a boue.

Bibliography

British Library (undated) Beowulf. Available online by clicking here.

British Library (undated) York Mystery Plays. Available online by clicking here.

Cawley, A. C. (ed.) (1977) Everyman and Medieval Miracle Plays. London: J. M. Dent and Sons.

Cawte, Heather (2016) Review: York Minster Mystery Plays. Available online by clicking here.

Chambers, E. K. and Sidgwick, F. (1907) Early English Lyrics. London: Sidgwick & Jackson.

Greene, Richard (ed.) (1962) A Selection of English Carols. Glasgow: Oxford University Press.

Gummere, Francis B. (transl.) (1910) Beowulf. Available online by clicking here.

Kline, A. S. (transl.) (2007) Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Available online by clicking here.

Little, Becky (2018) Rats Didn’t Spread the Black Death—It Was Humans. Available online by clicking here.

Montagu, Jeremy and Gwen (1998) Minstrels & Angels. Carvings of Musicians in Medieval English Churches. Berkeley: Fallen Leaf Press.

National Churches Trust (2023) St Mary. 900 years of worship in the heart of Oxfordshire. Available online by clicking here.

Pittaway, Ian (2019) Coventry Carol: the power of a song. Available online by clicking here.

Pittaway, Ian (2019) Foweles in þe frith (birds in the wood): mystery and beauty in a 13th century song. Available online by clicking here.

Regents of the University of Michigan (2023) Middle English Dictionary. Available online by clicking here.

Robertson, Elizabeth and Shepherd, Stephen H. A. (ed.) Piers Plowman. London: W. W. Norton.

Saint Mary’s, Cogges (undated 8 page booklet) A walk around St. Mary’s, Cogges. No publication details given.

Sargent, Peter (2017) 14th century 1349: The Plague Years. Available online by clicking here.