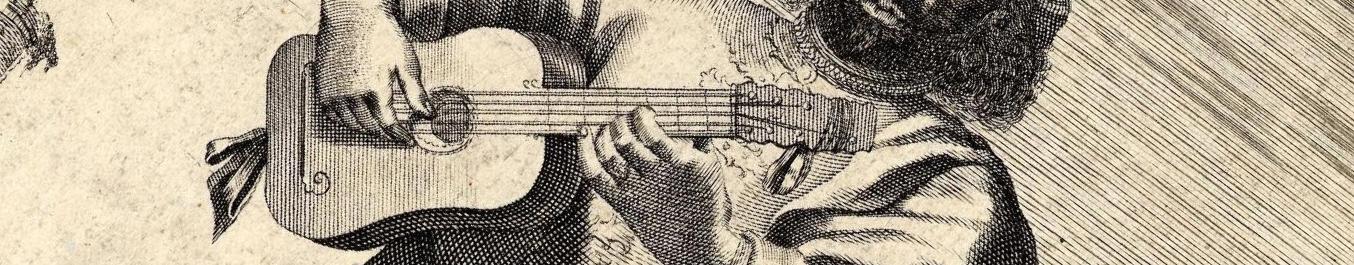

Richard Tarleton – fool, actor, playwright, poet, musician and legend – was the foremost stage clown of his age, celebrated in his own lifetime and well beyond. As an actor, he was a star of the stage when permanent theatre buildings were new, a fool or comedian of great physical and verbal wit, a serious player of affecting pathos, and a member of Queen Elizabeth I’s own acting company, The Queen’s Players. As a successful playwright, he wrote in the tradition of morality plays. As a poet and essayist, he wrote on the theme of natural disasters and divine displeasure. As a musician, he was a player of pipe and tabor and a creator of extempore comedy songs. As a legend, much-loved and much-missed after his sudden death, he was a byword for exemplary wit, his name used to sell literature for decades, his image still used and recognised two centuries later.

Richard Tarleton – fool, actor, playwright, poet, musician and legend – was the foremost stage clown of his age, celebrated in his own lifetime and well beyond. As an actor, he was a star of the stage when permanent theatre buildings were new, a fool or comedian of great physical and verbal wit, a serious player of affecting pathos, and a member of Queen Elizabeth I’s own acting company, The Queen’s Players. As a successful playwright, he wrote in the tradition of morality plays. As a poet and essayist, he wrote on the theme of natural disasters and divine displeasure. As a musician, he was a player of pipe and tabor and a creator of extempore comedy songs. As a legend, much-loved and much-missed after his sudden death, he was a byword for exemplary wit, his name used to sell literature for decades, his image still used and recognised two centuries later.

This is the first of four articles trawling 16th and 17th century sources to build up a picture of the man. This introductory article begins with a short history of fools in their three types – natural, ungodly, and artificial – to put Tarleton in his historical context; clarifies what contemporaneous writers meant when they described him as a jester; then describes his ‘country fool’ clown’s costume and notable physical appearance. Two neglected topics comprise the second and third articles. Part 2: Tarleton the player and playwright considers his range as a comic and serious actor and his style as a playwight, with an evidenced reconstruction of his lost play, The Secound parte of the Seven Deadlie Sinns. Part 3: Richard Tarleton the musician and broadside writer examines his style as a taborer; describes Tarleton as a comedic creator of extempore songs from themes called out by the audience; and surveys the evidence for Tarleton as a composer of ballads. Part 4: Tributes to Tarleton – with a musical discovery from the 16th century summarises the broadside ballads, books and plays which praised Tarleton and used his persona after his premature death. In particular, a musical biography of Richard Tarleton, A pretie new ballad, intituled willie and peggie, has its words and music reunited after 400 years of separation in a featured video performance.

Read more

This is the last of four articles about the life and music of Elizabethan clown, Richard Tarleton. Having examined the historical context of clowning; described his comic and serious stage roles and plays; and gathered the evidence for his pipe and tabor style and modern claims that he was a ballad writer; this final article surveys the way Tarleton was remembered posthumously, on the stage, in song, in books, in rhetoric, and in the commercial use of his famous image.

This is the last of four articles about the life and music of Elizabethan clown, Richard Tarleton. Having examined the historical context of clowning; described his comic and serious stage roles and plays; and gathered the evidence for his pipe and tabor style and modern claims that he was a ballad writer; this final article surveys the way Tarleton was remembered posthumously, on the stage, in song, in books, in rhetoric, and in the commercial use of his famous image.