Following on from the first article outlining the evidence for the citole’s multiple physical forms, string material and tuning, this second article examines the evidence for the citole’s playing style, repertoire, and the social contexts in which it was played. We examine the reliability of playing positions in iconography; overturn the modern myth that the thumb-hole restricts the fretting hand; show that the citole is easily capable of playing two voice polyphony; and give evidence for the musical genres citole players engaged in, including songs, jongleur (minstrel), troubadour and trouvère material, religious repertoire and dance music.

Following on from the first article outlining the evidence for the citole’s multiple physical forms, string material and tuning, this second article examines the evidence for the citole’s playing style, repertoire, and the social contexts in which it was played. We examine the reliability of playing positions in iconography; overturn the modern myth that the thumb-hole restricts the fretting hand; show that the citole is easily capable of playing two voice polyphony; and give evidence for the musical genres citole players engaged in, including songs, jongleur (minstrel), troubadour and trouvère material, religious repertoire and dance music.

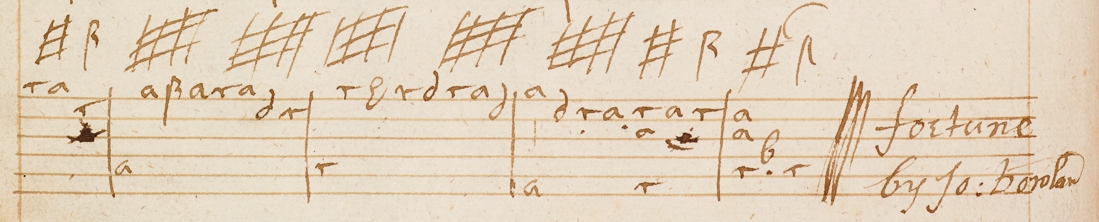

We begin this article with a video of La septime estampie Real – The seventh Royal estampie, c. 1300, played on a copy of the surviving British Museum citole.